Public universities, according to Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare, legal expert and Democracy and Development Fellow at CDD-Ghana, should not bear the names of politicians but reflect public character.

Prof. Asare argued that politicians’ inherently partisan and often divisive nature makes them unfit to have public universities—institutions meant to serve all Ghanaians—named after them, highlighting a broader debate about the identity and role of such institutions in Ghana.

According to him, the name of a university carries symbolic significance that transcends any single political moment and should not be exploited for fleeting political advantage.

He maintained that public universities should not be instruments of political legacy-building. Instead, they must reflect their national culture and public funding base.

Prof. Asare stated that naming them after politicians, especially while in office or within the immediate aftermath of political transitions, distorts their intended mission and alienates the broader public they serve.

“My long-standing view is that public universities in Ghana should be named based on geography (e.g., University of Cape Coast), mission (e.g., University for Development Studies), or both (e.g., University of Education, Winneba). This approach is not only principled—it is practical.

“Indeed, this is the model that has given us institutions such as the University of Ghana (UG), Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration (GIMPA), University of Cape Coast (UCC), University for Development Studies (UDS), University of Energy and Natural Resources (UENR), University of Health and Allied Sciences (UHAS), University of Mines and Technology (UMT), and University of Education, Winneba (UEW). It is a model rooted in national identity and public purpose.”

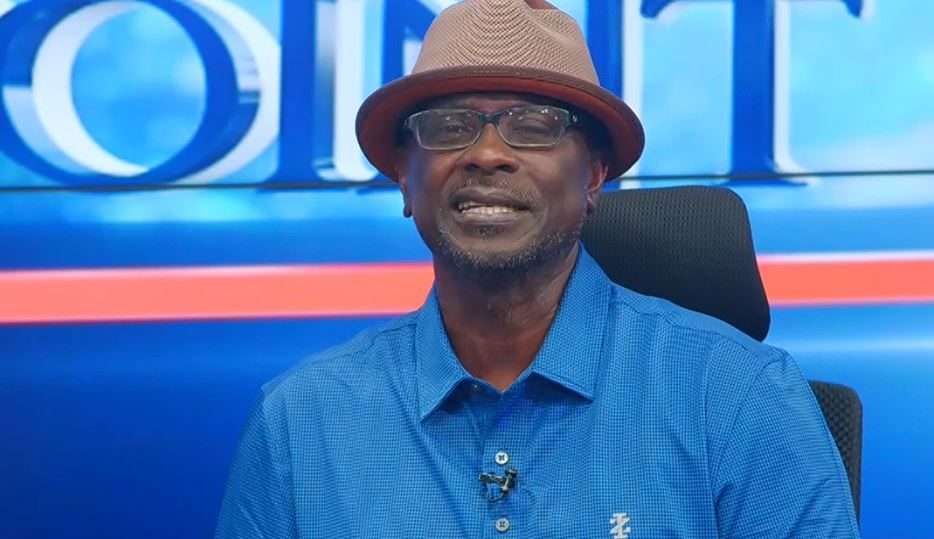

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

For Prof. Asare, the principle is simple: these are institutions established and sustained by the public purse, and therefore, their names should reflect the collective—not the individual.

He warned against the creeping trend of branding state-funded universities with partisan overtones, cautioning that it undermines institutional credibility and continuity. “Being in power does not make one the owner of public funds.”

Some have pointed to the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) as a counterexample.

However, Prof. Asare clarified an important distinction—KNUST was not renamed in tribute to Kwame Nkrumah, but rather established with that name through a legislative act in 1961.

The institution’s name was later changed by the National Liberation Council (NLC) to the University of Science and Technology, before being restored to its original designation in 1998 during the Rawlings administration.

“While this naming does not align with my preferred principles of geography or mission, I respect the legislative intent behind its original designation and acknowledge the strong brand identity KNUST has built over the decades. That said, KNUST is the exception—not the model to follow.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

Public Universities Encouraged To Serve Public Interest

Furthermore, Prof. Asare clarified that his position does not oppose the practice of naming university facilities—such as buildings, lecture halls, or institutes—after individuals who have made meaningful contributions to education.

However, he emphasized that such honors should be decided by university authorities, not politicians, and should be exercised with moderation.

“But even in those cases, University Councils must exercise restraint. They should respect the naming decisions of their predecessors. Otherwise, universities risk descending into naming wars—disrupting institutional continuity, confusing the public, alienating benefactors, and damaging their own brands.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

He observed that while disagreements over naming a library or science block can already create confusion, changing the name of an entire university has the potential to cause even deeper divisions.

According to Prof. Asare, such decisions should not be rushed or treated as political rewards; instead, they must consider institutional heritage, branding, public consensus, and the broader goal of long-term national unity.

He reminded the public that only Parliament—not the President—has the constitutional authority to rename a public university.

However, he cautioned, “power must be exercised with wisdom,” pointing out that just because Parliament can do it doesn’t mean it should, especially if it ignores broader societal implications.

Ultimately, Prof. Asare argued that Ghana must resist the urge to politicize its educational institutions.

Names matter—they shape perception, signal values, and outlast governments. When public universities are renamed to reflect party loyalty rather than national purpose, the damage is both symbolic and substantive.

“That is why I opposed the renaming of some of our public universities a few years ago. And it is why I will support any well-grounded effort to reverse those renamings and restore the integrity of our public academic institutions.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

In a time when the line between public interest and political branding is increasingly blurred, Prof. Asare’s perspective is a timely reminder that the country’s public universities belong to all Ghanaians, not the ruling party of the day.

His remarks come in the wake of ongoing national debates over the renaming of public universities—an issue that has resurfaced following the Education Minister’s recent disclosure that the current government intends to reverse name changes made during the previous NPP administration, reigniting concerns about political interference in academic institutions.

Ultimately, naming public universities should reflect national identity and enduring institutional values, rather than shifting political interests.

READ ALSO: Government Considers ‘Multiple Lease Model’ for ECG’s Privatization