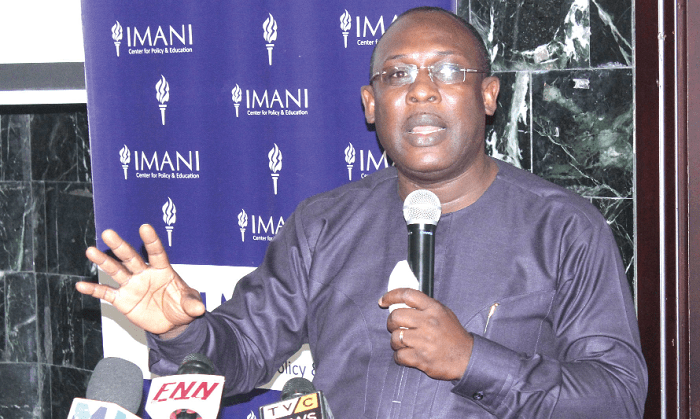

Amid ongoing public scrutiny of the fair trial implications in the case involving former Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta, Kofi Bentil, a lawyer and Senior Vice President of IMANI Africa, has offered a sharp legal rebuttal to critics demanding the accused’s physical presence at court.

His comments are the latest in a series of expert opinions prompted by concerns over the constitutionality of trying individuals in absentia.

Speaking on the matter, Bentil cited Article 19(3) of Ghana’s 1992 Constitution, which outlines the framework for criminal trials.

According to him, the article does state that trials are to be conducted “continuously in the presence of the accused,” unless the accused misbehaves or elects not to appear.

However, Bentil stressed that this interpretation should not be treated as an inflexible rule.

He explained that while presence at trial is a constitutional right, it is not a legal compulsion. “Presence at trial is a right, not an obligation.”

“The accused is granted the right to be present within the constitutional framework, which does not translate into a compulsion to show up if the accused can and prefers to do otherwise. This explains why the court has the discretion to move forward and adjudicate in absentia. This, too, needs to be judicially construed contextually.”

Kofi Bentil

He noted that judicial precedent supports this flexibility. In the case of Arthur v. Republic [1972] 2 GLR 141, Bentil explained, the court ruled that although an accused cannot be unjustly denied the right to attend a hearing, trials can still proceed lawfully when the absence is deliberate and proper service has been made.

He pointed out that while the prosecution is not permitted to block an accused person from attending their hearing, “if the accused fails to appear without valid justification, the trial process should not be forced to a standstill.”

Presence, Not A Legal Obligation For Fair Trial

Furthermore, Kofi Bentil explained that even though the law does not expressly grant a “right to be absent,” the judicial system does permit trials to continue in an accused person’s absence when justified by the circumstances.

He emphasized that a court’s authority to proceed is not limited to cases of misbehaviour or absence alone, but also includes situations where justice requires the trial to move forward.

He also drew a parallel between an accused person’s right to remain silent and the choice to be absent from trial, arguing that both rights function as legal safeguards designed to protect the individual within the judicial process.

“It is arguable that the constitutional protections afforded a person to remain silent and refuse to testify are coterminous with the right to let the trial proceed without them.”

Kofi Bentil

Bentil also invoked the Criminal and Other Offences (Procedure) Act, 1960 (Act 30), specifically Section 167, to support his position.

The Act allows for a bench warrant and trial in absentia — but only if the necessary legal procedures are followed, such as proper service of summons and a determination that the absence was voluntary or justified.

“This flexibility is crucial because it addresses the concern where an accused person returning to the jurisdiction could expose them to the prejudice, bodily harm, or unfair trial recognised in international human rights law, such as: Soering v. UK (1989) ECHR 14, where the European Court of Human Rights ruled that states have an obligation to assess all risks of non-adjudicative harmful treatment before enforcing in-person appearances or extradition.”

Kofi Bentil

Accordingly, Bentil emphasized that Act 30 offers adequate legal support for cases where an accused person opts not to appear in court.

He noted that the legislation clearly anticipates such scenarios and includes specific provisions to address them.

Tried In Absentia

The IMANI Vice President also clarified that Ghana’s legal framework does not impose an absolute duty to surrender to the court. Situations such as medical incapacity, potential public backlash, or a lack of safety and fairness guarantees may justify absence.

“In such cases,” he said, “the State has full legal rights to prosecute in absentia and can seek post-conviction extradition.”

Summarizing his position, Bentil argued that Articles 15 through 19 of the Constitution collectively support the continuity of trials even when the accused is not present, provided due process is followed.

“Not returning under deeply unfriendly circumstances does not equate to a right to be absent, but neither is it unlawful — especially when the State has other legal avenues available.

“The Constitution guarantees a fair trial, not pageantry, for the public. The spirit of the law is to achieve justice, not to lynch accused or even criminals through law or the arms of authority.”

Kofi Bentil

In a closing remark aimed at critics demanding Ofori-Atta’s presence, Bentil argued that insisting the trial cannot proceed without direct engagement with the accused reflects a lack of confidence in the strength of the prosecution’s case.

He stressed that building a solid case and achieving a conviction requires diligent effort, not performative gestures, and maintained that it is fully within the prosecution’s discretion to continue with or without such displays.

Meanwhile, the legal framework allows for trials to proceed in the absence of the accused under specific conditions, ensuring that justice is not unduly delayed.

Courts, therefore, maintain discretion to balance the right to a fair trial with the practical realities of each case, including situations where the accused chooses not to appear.

READ ALSO: National Guard Troops Arrive In Los Angeles Following Protests Against ICE Raids