The Asantehene, Otumfuo Osei Tutu II, recently ignited discussion across Ghana’s political and resource governance landscape with his call for a constitutional review to reassign greater control over mineral rights to traditional authorities.

The monarch proposes that chiefs gain enhanced licensing oversight within their jurisdictions rather than merely receiving downstream royalties.

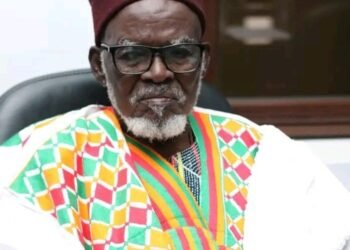

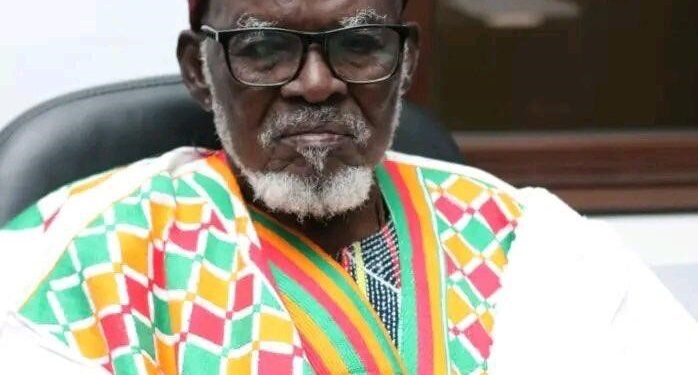

In an exclusive interview with the Vaultz News, mining expert Ing. Wisdom Edem Gomashie explained potential benefits and tensions such a shift might entail within Ghana’s extractive sector governance.

“Currently, our laws do not place traditional authorities in a very good position for them to have a say, an administrative say, in who gets a license or what is done in their district.”

Ing. Wisdom Edem Gomashie, a prominent mining consultant

He referenced LI 2176-2012, the Legislative Instrument governing small-scale mining, which only requires notifying chiefs after mining applications have already been submitted.

He also pointed to Section 92 of the Minerals and Mining Act (Act 703), which establishes district-level small-scale mining committees with traditional leaders as members. However, he noted that these committees are poorly resourced and lack the authority or funding to be effective.

Ing. Gomashie advocated for a significant revamp of these committees. Rather than creating new institutions, he suggested strengthening the existing framework by empowering chiefs with clear administrative mandates, vetting responsibilities, and adequate financial resources to participate meaningfully in mining governance.

“If we have a system like that, we will not have a situation whereby chiefs will say they are not involved in licensing again.”

Ing. Wisdom Edem Gomashie, a prominent mining consultant

In his words: “Let’s give them mandates, so that every mining application within the district… they should have a say” to avoid chiefs being excluded again.

Centralized Ownership Debate

The debate over mineral rights is closely tied to the broader question of governance, namely who gets to decide what happens beneath the surface of Ghana’s resource-rich land.

For decades, Ghana has operated under a centralized ownership model, with the President holding mineral rights in trust for the nation. Constitutionally, Section 6 of Article 257 vests ownership of all underground minerals in the President for the benefit of Ghana.

This system is common across Africa and aims to prevent fragmentation of mineral ownership, ensuring that resource benefits are shared nationally. In. Gomashie believes the current arrangement is a mixed bag.

“I cannot for 100% say the current ownership has served Ghana too well, and I can also not conclude that the current centralized nature of the ownership of our minerals has also marginalized local stakeholders.

“We are in between. We are not doing bad; we are not doing too good.”

Ing. Wisdom Edem Gomashie, a prominent mining consultant

He contrasted Ghana’s model with that of the United States, where mineral rights belong to the landowner. In Ghana, traditional authorities hold surface rights, but the minerals underground remain the purview of the state.

This disconnect often creates friction, especially when mining licenses are issued without proper consultation with chiefs or communities.

Ing. Gomashie stressed that while central ownership can be effective, it must be complemented with transparent practices and community engagement to ensure equitable benefits.

He believes granting chiefs a formal role in licensing decisions must come with clear responsibilities—and consequences. If empowered, they must also be held accountable.

“Let’s recognize them … but those responsibilities should also come with penalties.

“So tomorrow, if a chief is caught perpetuating or aiding illegal mining… that should be dealt with severely”

Ing. Wisdom Edem Gomashie, a prominent mining consultant

Community Revenue Sharing: 1% Allocation Proposal

Another governance proposal under consideration is requiring mining companies to allocate 1% of gold sales revenue toward community development.

The initiative, modeled after practices by companies like Gold Fields Ghana and Newmont, has the potential to significantly transform mining communities.

“Currently, mining companies determine their corporate social responsibility CSR budgets. I have written papers advocating for the government to legislate CSR activities across all productive sectors.”

Ing. Gomashie supported this idea, projecting it could transform mining districts. For instance, a town like Tarkwa could receive up to $30 million annually, enough to fund hospitals, schools, and local infrastructure.

He drew on examples such as Atlantic Lithium’s agreement to channel 1% of its lithium revenues into community investment, though this remains informal pending legal backing.

However, incentivising such allocations also carries risks of elite capture and mismanagement. Ing. Gomashie recommended that these funds be managed jointly by government, mining firms, and communities under transparent frameworks, and not solely by companies or by local elites.

If successfully implemented, the proposed reforms could strengthen local ownership of mining benefits, improve accountability, and reduce disenfranchisement in mining communities.

Incorporating chiefs in licensing could foster more inclusive governance and preempt local resistance to mining projects.

Yet without clear institutional design, funding and integrity safeguards, these changes risk being tokenistic or creating new corruption vectors. Strengthening existing statutory bodies, rather than creating parallel institutions, is critical to institutional coherence.

Moreover, aligning constitutional ownership with community benefit requires mechanisms to ensure revenue transparency, enforce social contracts, and create enforceable obligations for mining firms.

Current reforms (85% complete) under the new Minerals and Mining Act include mandatory revenue-sharing models, short licence durations, and community development requirements—measures consistent with the issues raised by the Asantehene.

The Asantehene’s call has ignited debate over mineral governance in Ghana. While the centralised ownership model is entrenched, there is growing recognition that communities need stronger roles in licensing, revenue sharing, and oversight.

Experts like Gomashie argued for calibrated reforms, not symbolic gestures, to expand traditional authorities’ administrative powers within existing legal structures, backed by funding, accountability, and transparency.

From a governance perspective, the stakes are high: if executed well, Ghana could pioneer a more inclusive extractive governance model; if managed poorly, reforms could deepen fragmentation, local conflict, and elite capture.

For now, the conversation has opened, what remains is turning demand into durable institutional change.

READ ALSO: Bright Simons Critiques Ghana’s Sports Infrastructure: Misplaced Priorities and State Enchantment