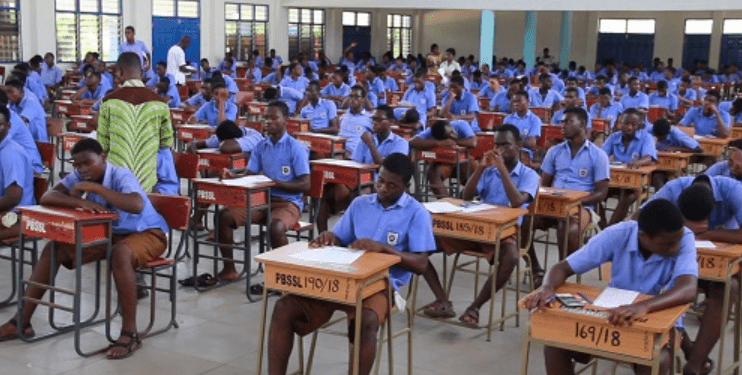

Education emergency planning in Ghana is facing sharp scrutiny as final-year students in Bawku and Nalerigu prepare to sit the West African Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE) amid escalating conflict.

Dr. Peter Anti, Executive Director of the Institute for Educational Studies (IFEST), raised concerns over the lack of structured emergency response mechanisms to ensure educational continuity in such volatile regions.

According to Dr. Anti, this critical lapse is not a recent oversight. Global discussions around education in emergency settings gained traction during the COVID-19 pandemic, prompting many countries to adopt contingency plans to safeguard learning in times of crisis.

Ghana, however, has yet to implement any meaningful protocols. Despite donor-funded research aimed at creating frameworks for emergency education delivery, those plans remain dormant, leaving affected students in precarious situations.

“Ghana does not have those protocols. We have not been able to finalize and kickstart anything on educational emergencies. This does not refer only to final year students. It includes the second and the first years who are also supposed to undergo education. Basically, we say that education should not stop because of an emergency situation.”

Dr. Peter Anti

While other countries have established systems that activate automatically during crises—ensuring continuity in education—Ghana has not developed similar models, leaving students and educators vulnerable to conflict-related disruptions.

Students currently face a host of difficulties, from displacement to inadequate academic support.

In some cases, learners are being driven from their home communities under military and police escort just to reach examination centers.

This scenario, Dr. Anti suggested, not only exposes them to physical risk but also severely impacts their mental readiness for examinations.

Exam Relocation Poses Mental Strain on Students

Addressing proposals that students be relocated to other schools to take their exams, Dr. Peter Anti highlighted the intense psychological toll such a move could impose.

He pointed out that being forced to wake up at dawn, travel under military or police escort, and arrive at an unfamiliar school just before taking a critical exam can have a deeply unsettling effect on students’ mental readiness and performance.

He argued that these logistics can deeply influence student performance, noting that environmental factors often determine academic success as much as personal ability.

“You cannot ascribe a particular factor to a student’s performance,” he noted, highlighting how compounded stress factors may skew results unfairly against students from crisis-hit regions.

Accordingly, Dr. Anti proposed that affected students should be relocated entirely to safer school environments before exams begin.

By doing so, students would have time to acclimate, access preparatory classes, interact with teachers, and enjoy the stability required to perform well.

This approach would also allow them to participate in nightly studies or “prep,” just like their peers in less affected regions.

Furthermore, Dr. Anti suggested collaboration with non-governmental organizations such as SEND Ghana, which have the infrastructure and technology to step in during emergencies.

These agencies can operate effectively with clear guidelines from the government, enabling rapid deployment of educational resources when crises erupt.

Calls Grow For Education Emergency Protocols

However, coordination remains a significant gap. According to Dr. Anti, stakeholders must move beyond discussions and begin implementation.

Ghana has witnessed repeated incidents of violence and instability in schools—not just in conflict zones like Bawku but in other parts of the country as well.

Since January, IFEST has recorded six to seven cases of gun-related incidents and similar disruptions in secondary schools.

“This is not the only situation,” he warned. The frequency and spread of these incidents suggest that emergency education protocols are not just optional but essential for the future of Ghana’s youth.

The absence of such systems means every time violence breaks out, education grinds to a halt, compounding the trauma for affected students.

The urgency of the situation demands immediate attention. Emergency educational protocols are not a luxury; they are a necessity in an increasingly unpredictable national and global landscape.

The current crisis in Bawku and Narelugu should serve as a wake-up call for policymakers, education officials, and international partners.

Time is running out for students forced to navigate bullet-riddled streets and armed convoys just to sit for an exam.

The longer it takes to develop and implement actionable protocols, the more Ghana risks a generation of learners left behind—not for lack of potential, but for lack of preparedness by the system meant to protect them.

READ ALSO: Actress Decries Editor Gap in Ghana’s Movie Industry