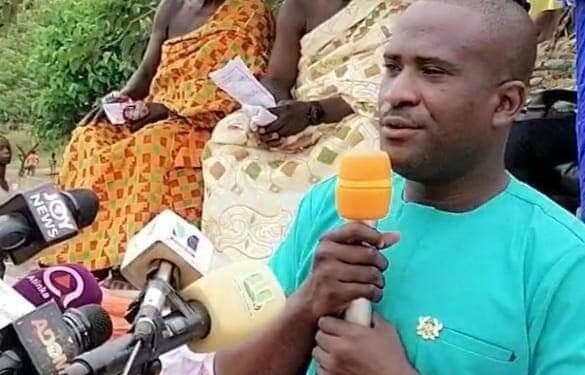

Kay Cudjoe, a market researcher and IMANI Africa contributor, has issued a sharp rebuke of the recent involvement of the Bar Council of England and Wales (BCEW) and the Commonwealth Lawyers Association (CLA) in matters concerning the Ghana Judiciary and the suspended Chief Justice Gertrude Torkornoo.

According to him, the tone and posture of these bodies reflect a disturbing colonial hangover rather than genuine legal solidarity with Ghana’s judicial process.

Cudjoe described the communique as an “exhibition of breathtaking” arrogance, one that assumes Ghana remains beholden to imperial authority.

He stressed that this was not the language of peers in the global legal fraternity but the posture of an empire attempting to reassert dominance over its former colonies.

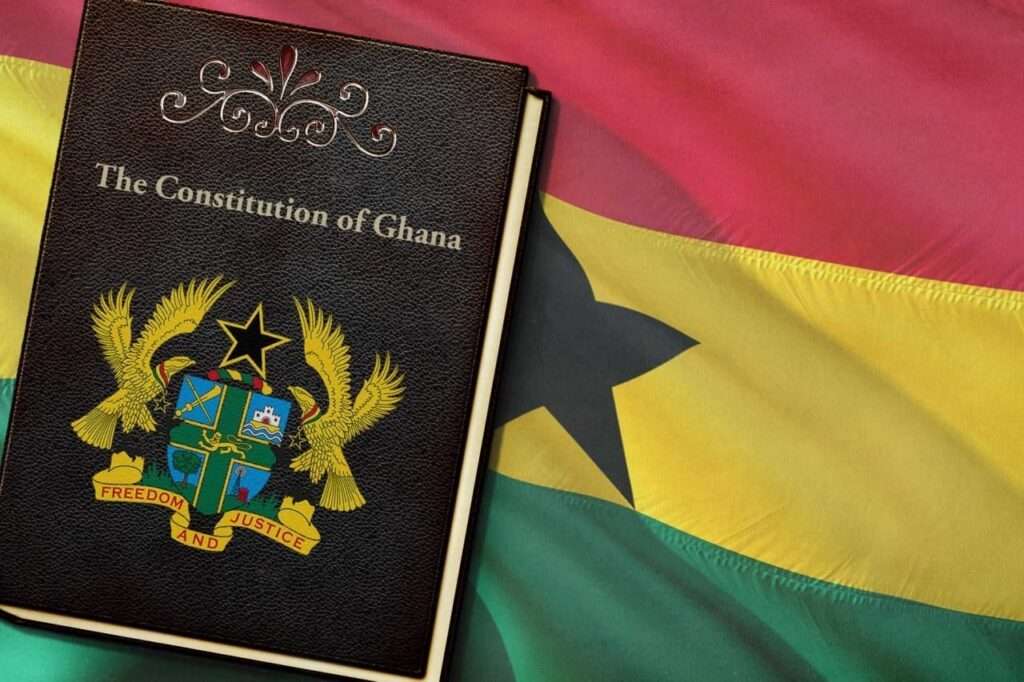

The Ghana Judiciary, he argued, does not owe its allegiance to London or its institutions but to the sovereign will of Ghanaians under the 1992 Constitution.

“Broni Wewu: Somewhere in London…, in a mahogany room lined with portraits of dead men in powdered wigs, someone with the brain of a needle banged a silver spoon on a teacup and declared: ‘We must teach those brutes in Ghana the rule of law, if not colonial comport.’

“And so, the Bar Council of England and Wales (BCEW), together with the Commonwealth Lawyers Association (CLA), issued a communiqué in a tone more suited to a colonial district officer than to a 21st-century peer. It demanded that Ghana ‘immediately and without delay’ reinstate our suspended Chief Justice, Her Ladyship Justice Gertrude A.E.S. Torkornoo. Not ‘urge.’ Not ‘recommend.’ No, command. As if 6th March 1957 never happened.”

Kay Cudjoe

In his analysis, Cudjoe pointed out the irony of Britain, through its legal establishment, lecturing Ghana on due process.

He reminded observers that this was the same system that historically exiled African kings without trial, detained nationalists without charge, plundered natural wealth, and once filled colonial courtrooms with magistrates whose loyalty lay with the Crown rather than with justice.

To now parade the Latimer House Principles as though they invented judicial ethics, he added, is a historical distortion that ignores the lived experiences of those who endured British rule.

Demands That Reek of Colonial Muscle

For Kay Cudjoe, the hypocrisy in this intervention was striking. He explained that Attorney-General Dr. Dominic Ayine had already laid out, with precision, the constitutional framework guiding the suspension.

Article 146 of the 1992 Constitution stipulates that petitions from Ghanaian citizens must be examined by the Council of State.

Upon finding a prima facie case, a committee chaired by a sitting Supreme Court Justice is constituted, and the President, acting strictly under the law, suspends the Chief Justice pending investigation. This, Cudjoe emphasized, is what occurred.

“No executive overreach. No shortcuts. No colonial oversight required. Yet the BCEW/CLA statement blithely ignores these constitutional steps, waving the Latimer House Principles like a colonial ordinance.”

Kay Cudjoe

He regretted that the BCEW and CLA seemed to elevate external frameworks as though they carried greater authority than the nation’s own supreme law.

Cudjoe interpreted this as an act of jurisdictional nostalgia — a longing for the days when Ghana’s judiciary functioned as an annex of Westminster.

This intervention, he argued, was not about justice but about the preservation of influence, a subtle attempt to reassert British authority in spaces where it no longer belongs.

Ghana Judiciary To Chart Its Own Path

Accordingly, Cudjoe emphasized that Ghana’s commitment to judicial independence stems from its own resolve and historical lessons, not from external pressures or reminders from foreign institutions.

He stressed that due process will be upheld because the nation understands the cost of injustice, not because of symbolic gestures from outsiders.

For him, the principle is clear: if the Chief Justice is to be reinstated, it will be determined solely under Ghanaian law and by the Ghanaian people. It will not be dictated by letters sent from foreign associations still clinging to an outdated sense of global dominance.

“So to our learned friends in England and Wales, keep your wig on. The days when Ghana’s judges took instructions from Whitehall are gone. The empire’s bench is buried. The gavel is ours.”

Kay Cudjoe

Cudjoe noted that while outsiders may choose to disagree with the processes or raise doubts about their fairness, the issue remains firmly within Ghana’s sovereign authority to resolve.

He concluded by stressing that while Ghana welcomes dialogue and cooperation with global legal institutions, it rejects the imposition of external authority that undermines its independence.

This, he said, is not unfinished colonial business to be tidied up by those still nostalgic for empire, but a matter of Ghana’s sovereign right to administer justice according to its Constitution.

The controversy surrounding the suspension of Chief Justice Gertrude Torkornoo has thus evolved into more than just a legal debate. It is a symbolic confrontation over Ghana’s post-colonial identity, judicial sovereignty, and the lingering shadows of empire.

Cudjoe’s remarks serve as a reminder that the Ghana Judiciary will continue to be guided not by dictates from abroad but by the will of its people and the rule of its Constitution.