Ghana’s democracy and development are being undermined not just by overt acts of corruption or mismanagement, but by the silent acceptance of practices that should never have been tolerated in the first place.

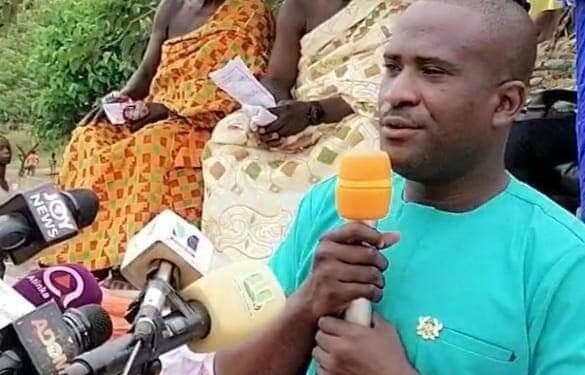

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare, a respected governance advocate and Fellow at CDD-Ghana, has drawn attention to these troubling realities in a thought-provoking reflection he titled “Top Ten Abnormal Things We Have Normalized.”

In his essay, Professor Asare outlined a troubling pattern of cultural, political, and institutional habits that have been embraced as “normal” despite their destructive consequences.

According to Professor Asare, one of the most glaring of these is the continued acceptance of illegal mining, popularly known as galamsey, as a legitimate livelihood. He argued that while small-scale mining is often justified as a source of income for communities, the devastating environmental cost is undeniable.

“It destroys rivers, forests, and food security. Galamsey is an existential threat to future generations, proof of our preference for ‘now’ at the expense of tomorrow,” he lamented. For him, the normalization of such a destructive practice is a betrayal of posterity and a sign of misplaced priorities.

Equally disturbing is the trend of encroachment on protected reserves. Professor Asare noted that forests and lands meant to safeguard the environment are being casually converted into real estate properties.

Occasionally, there are publicized demolitions of illegal structures, but he insisted that such actions are too little, too late. “They should never have been allowed in the first place,” he stressed. To him, the state’s complicity in permitting such developments reflects weak governance and selective enforcement of laws.

The culture of glossing over audit findings is another critical area of concern. Every year, Professor Asare decried that the Auditor-General’s reports highlight massive financial losses, waste, and fraudulent transactions within state institutions, yet these are conveniently described as “irregularities.”

For Professor Asare, this is a dangerous euphemism that downplays the gravity of corruption. “Billions are drained, schools and hospitals starved, institutions weakened, yet we shrug,” he remarked, pointing to a systemic rot that undermines accountability.

Ex Gratia Bonanza

He also drew attention to what he termed the Ex Gratia Bonanza, describing it as “the most risk-free profit-making venture.” Politicians and public officers, he argued, exploit a system that allows them to retire on their regular pensions and still collect hefty ex gratia packages. This practice, he believes, entrenches inequality and deepens public mistrust in political leadership.

The monetization of internal party elections is yet another troubling abnormality. Professor Asare described party primaries as a “cash-and-carry democracy,” where money rather than merit determines who emerges as a candidate.

“Now this culture is creeping into general elections; money, not merit, chooses leaders,” he warns. This, in his view, erodes democracy and sidelines competent individuals who cannot afford the financial demands of political contests.

Investigation Bodies under Siege

Beyond politics, he highlighted the troubling phenomenon of mobs gathering at the Economic and Organized Crime Office (EOCO) to block lawful investigations against powerful figures.

This trend, he argued, sends a dangerous message: “EOCO should only chase ‘small people,’ not the big men.” Such acts of interference in justice processes reinforce inequality before the law and embolden impunity.

Professor Asare further lamented how the legal system itself enables injustice through endless adjournments of court cases. He described adjournments as a deliberate defense strategy that allows cases to drag on until witnesses lose interest, evidence weakens, or the matter simply dies.

“Justice delayed becomes justice denied and impunity thrives,” he observed, pointing to a judiciary that risks losing credibility if such practices persist.

Land litigation, he noted, is another abnormality that has been accepted as part of Ghanaian life. Disputes over ownership drag on for decades, trapping families and investors in endless battles.

Even so-called high-end gated communities are not spared. “Owned it for three decades is no guarantee,” Professor Asare emphasized, highlighting the insecurity of property rights in the country.

On the roads, he identified indiscipline as a deadly cultural norm. Wrong-way driving, reckless speeding, and blatant disregard for traffic regulations have become everyday occurrences.

Yet society treats them as normal, even as needless accidents claim lives and cripple productivity. “Productivity and lives are lost daily,” he warned, urging stricter enforcement of road safety laws.

Post-Harvest Losses

Finally, Professor Asare pointed to the tragedy of post-harvest losses (PHL). Despite Ghana’s capacity to produce enough food, poor storage facilities and neglect cause large portions of harvests to go to waste. Hunger, he argued, has thus become “man-made.”

In a lighter reflection, he recalled how the concept of post-harvest losses fascinated him as a student. “PHL was my favorite term as a secondary school student. It appeared in all my ‘O’ level answers, no matter the subject,” he reminisced. Yet, decades later, Ghana still struggles with the same problem.

In weaving together these ten “normalized abnormalities,” Professor Asare painted a sobering picture of a society that has lost its sense of urgency to confront wrongdoing.

His reflections call for a national awakening, urging Ghanaians to rethink what is acceptable and challenge practices that undermine development and justice. The danger, he implied, lies not only in the wrong itself but in the culture of acceptance that shields it from reform.

READ ALSO: Inflation Pressures Ease, But August CPI Faces ‘Upside Risk’ from Base Effects