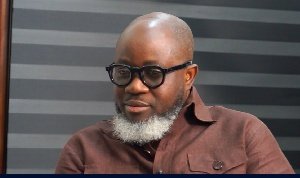

Ghana’s secondary and tertiary education sector has expanded significantly over the past decade, with more young people gaining access to classrooms than ever before. But this progress in enrolment, according to Kofi Asare, Executive Director of Africa Education Watch, does not automatically translate into the development of skills that match the demands of the labor market.

Writing in response to recent findings in the World Bank’s 2025 Policy Note: Transforming Ghana in a Generation, Mr Asare emphasized that the country’s education system, while growing in size, is struggling to equip graduates with the practical competencies needed to drive innovation, productivity, and sustainable employment.

He cited a 2021 analysis that revealed a stark mismatch between graduate output and industry requirements. “Only 10 percent of graduates secured jobs within a year of graduation,” Mr Asare noted, adding that this deepens the already alarming problem of youth unemployment.

The situation is compounded by the fact that 1.9 million Ghanaian youth, mostly women, are neither engaged in education, employment, nor training (NEET), leaving them excluded from pathways to economic participation.

The imbalance between academic choices and labor market needs is another dimension of the problem. At the senior secondary and tertiary levels, arts programmes dominate enrolment, while STEM disciplines—such as science, technology, engineering, and mathematics—remain underrepresented.

TVET Underfunded

The result, Mr Asare warned, is a pool of graduates whose skills fail to meet the practical and technological needs of Ghana’s modern economy. Technical and vocational education and training (TVET), often seen as the bridge between education and industry, has been chronically underfunded.

According to the Eduwatch Boss, in 2021, only 4 percent of the national education budget was allocated to TVET, a figure that lags behind the sector’s potential to produce skilled workers.

Beyond underfunding, Mr Asare pointed to deeper systemic weaknesses, including the limited role of industry in shaping academic programmes, the absence of a national system to track labor market trends for academic planning, and insufficient investment in practical STEM training.

“Engineering makes solid labour-market sense in Ghana,” Mr Asare remarked, sharing a personal anecdote about his nephew’s academic journey as an example of the opportunities STEM and TVET can provide. His nephew, recently admitted to Koforidua Technical Institute (KOTECH), a Category A TVET school, will pursue electrical engineering with a clear pathway to higher education and eventual employment.

“Next stop is a Bachelor of Technology in Electrical and Electronics Engineering at Koforidua Technical University. After that, he can choose a Master of Technology in Sustainable Electrical Power Engineering at Accra Technical University or move straight into the world of work”.

Kofi Asare, Executive Director, Africa Education Watch

TVET and STEM Drive Employment

Unlike many arts graduates who depend on government recruitment drives to find employment, engineering and technical skills are market-responsive and create independent opportunities. “He won’t need to depend on government recruitment after university—skills like these create their own opportunities,” Mr Asare stressed, highlighting how strategically investing in STEM and TVET can open practical avenues for Ghana’s youth.

The World Bank’s 2025 Policy Note echoes these concerns and proposes a series of recommendations to address the gaps in Ghana’s education sector. First among them is the implementation of a ‘foundational learning package’ in all basic schools to ensure literacy and numeracy standards are met.

The report also emphasized the importance of strengthening governance and efficiency in education spending by addressing teacher absenteeism, improving deployment, and ensuring schools are adequately resourced.

Another critical recommendation focuses on increasing the relevance of secondary education, particularly by expanding STEM and promoting industry-led skills development. Special attention is urged toward adolescent girls, who remain disproportionately disadvantaged in accessing STEM opportunities.

Additionally, the report called for school-based programmes aimed at reducing gender-based violence, ensuring that both boys and girls can learn in safe environments. For Mr Asare, these recommendations are timely and necessary but must be matched with practical action.

The mismatch between what Ghana’s schools are producing and what its industries require is not only a matter of education policy but also one of national economic survival. A youth population ill-equipped for the demands of modern work, he argued, risks undermining the country’s transformation agenda.

The urgency of reform is underscored by demographic realities. Ghana’s population is young, with nearly 60 percent under the age of 25. Harnessing this demographic dividend requires building a workforce ready for the challenges of technology, green energy, and industrialization, rather than one concentrated in sectors with limited job creation capacity.

Mr Asare’s reflections suggest that Ghana’s education system stands at a crossroads. While access has improved, the relevance and quality of training lag behind. His nephew’s journey through technical education, positioned as a model of market-ready preparation, demonstrates that with the right investments, Ghana can align its education outputs with labor market demands.

Ultimately, bridging the skills gap will require more than just enrolment growth. It will depend on deliberate policy choices: prioritizing STEM, funding TVET, involving industry in curriculum design, and ensuring that graduates emerge with practical, employable skills.

As the World Bank report and Mr Asare both stress, Ghana’s ability to transform “within a generation” will hinge on how effectively it prepares its youth today for the realities of tomorrow.

READ ALSO: Ghana Forms Mining Audit Committee to Tackle Sector Irregularities