A new study conducted by researchers from Loughborough University, Australian institutions, and U.S. universities reveals a grim outlook for the future of global food production.

The research predicts that rising temperatures will significantly impact farmers’ physical capacity to work, potentially leading to a drastic reduction in labor productivity by the end of the century. Key food production regions, including Pakistan and India, could experience a staggering 40% decline in labor productivity, while other crucial areas may see a reduction to 70%.

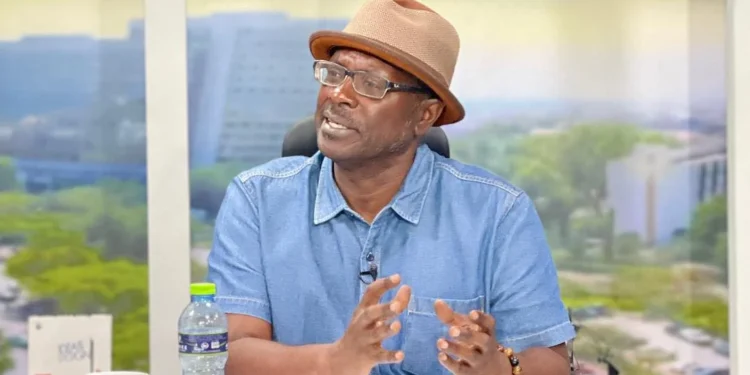

The study, led by Professor Gerald Nelson of the University of Illinois, sheds light on the often-overlooked consequences of climate change on the physical well-being of agricultural workers. While discussions around climate change often focus on its impact on crops and livestock, this research underscores the broader repercussions on the human labor force responsible for planting, tilling, and harvesting the world’s food supply.

The findings indicate that labor productivity in key food production regions such as Pakistan and India could witness a precipitous drop to as low as 40%. Other critical crop-growing areas in Southeast and South Asia, West and Central Africa, and northern South America are also expected to experience a substantial reduction in physical work capacity, with projections indicating a potential decrease to 70%.

Professor Gerald Nelson emphasized that the consequences of climate change extend beyond reduced crop yields, exacerbating existing food security challenges. As the study highlights the potential decline in the physical ability of agricultural workers due to heat exposure, concerns are raised about the overall capacity of the global food production system to meet the demands of a growing population.

Addressing the Human Element in Climate Change

While the study reinforces existing concerns about the environmental impact of climate change on agriculture, it brings attention to the human element in the equation. It calls for a more comprehensive approach to climate change mitigation that not only considers crop resilience but also addresses the well-being and resilience of the workforce crucial to sustaining global food production.

Published in the journal Global Change Biology, the study, titled “Global reductions in manual agricultural work capacity due to climate change,” involved using computational models to predict the physical work capacity (PWC)—defined as “an individuals work capacity relative to an environment without any heat stress”—under different predicted climate change scenarios.

The models, developed by Loughborough University, are based on data from more than 700 heat stress trials—which involved observing people working in a wide range of temperatures and humidities, and differing weather conditions, including sunshine and wind.

The maximum work capacity achievable by individuals in a cool climate was used as the benchmark for the study—representing 100% physical work capacity.

Reductions in capacity mean people are limited in what they can physically do, even if they are motivated to work. This may translate as farmers needing extra workers to do the same job, or if these are not available, then reducing their crop sizes.

Agricultural workers are already feeling the heat, the study reveals, with half the world’s cropland farmers estimated to be working below 86% capacity in “recent past” (1991–2010) climate conditions.

As a next step, the study considered potential adaptations to mitigate the impact of climate change on agricultural workers. Switching to night-time or shade work to reduce direct solar radiation, was shown to lead to a 5%–10% improvement in worker productivity.

A second investigated option is to increase the global use of mechanical machinery and equipment, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, where agricultural practices largely involve hard physical labor.

Of the importance of the study, Loughborough University’s Professor George Havenith said, “This research demonstrates once again the large impact climate change will have on life in various regions around the world, and quantifies the effects on agricultural productivity”.

“Understanding the full impact of climate change on worker productivity enables us to predict the economic impact of climate change and guide mitigation efforts that ensure we keep workers safe while limiting productivity losses. We hope the suggested adaptations can help guide investments to support agricultural workers and food security as climate change makes the outdoor working environment increasingly inhospitable.”

Professor George Havenith

READ ALSO: Donewell Insurance Introduces ‘Esi Donewell’ for Seamless Insurance Purchase