Bright Simons, Honorary Vice President of the IMANI Centre for Policy and Education, has provided insights into Africa’s evolving economic relations with the United States.

Simons highlighted the relatively low level of trade and investment between Africa and the US, suggesting that African countries could benefit from a more tactical approach by engaging directly with individual US states rather than relying solely on federal-level diplomacy.

“Many countries are unhappy about America’s seeming aloofness when it comes to reciprocating their interest in a more strategic partnership,” Simons remarked. He noted that African analysts believe increased US trade and investment could be realized if America adopted a more strategic posture toward the continent.

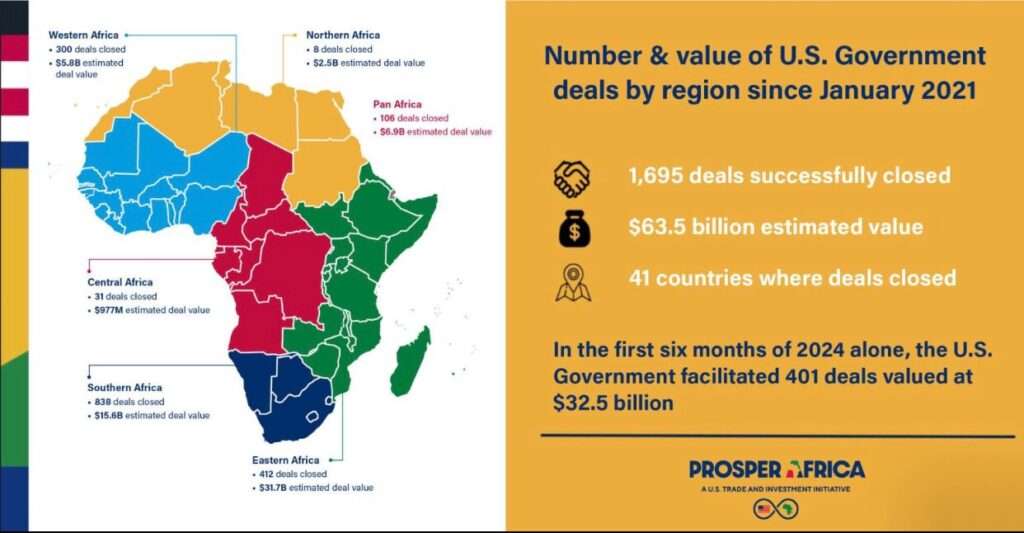

The statistics shared by Simons painted a stark picture of the limited scope of US-Africa trade and investment.

“Trade between Sub-Saharan Africa as a whole and the US amounted to less than $50bn in 2023. This is 0.7% of total US trade.”

Bright Simons, Honorary Vice President of the IMANI Centre for Policy and Education

Interestingly, the trade and investment flow between Africa and the US is not unidirectional. African investments in the United States reached $10 billion in 2021, which constituted nearly 3% of total FDI into the US, as per the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

Simons referred to this African investment as “interesting but not spectacular,” highlighting that while some African nations do invest in the US, the scope remains limited relative to the broader economic picture.

Simons urged African leaders to reconsider their strategy, suggesting that Africa’s economic leverage with the US at the federal level is minimal. This imbalance, he explained, necessitates a more nuanced and localized approach.

“There is good reason for African countries to begin considering strategic direct engagements with US states where their leverage could be more substantial,” Simons emphasized.

He acknowledged that African countries might see this approach as a concession, yet he argued that engaging at the state level could yield more pragmatic outcomes.

African Nations Might Target Individual US States for Strategic Partnerships

“America is quite decentralized compared to some of Africa’s other strategic counterparties like India and China,” Simons pointed out. Unlike the US, countries such as India and China have strong central governments that facilitate a cohesive approach to international economic engagements.

The US federal structure, however, disperses substantial power across its 50 states, each with its own policies, regulations, and economic agendas. This decentralization offers African countries an opportunity to build direct ties with individual states whose economies and growth trajectories could align with African interests.

In a striking comparison, Simons highlighted that four US states – California, Texas, New York, and Florida – possess economic power comparable to that of the African continent.

California’s GDP, for instance, already surpasses Africa’s combined GDP, and with similar growth rates, California will likely maintain its lead. Texas, which has a GDP roughly 10% smaller than Africa’s, is growing at twice Africa’s rate and is expected to surpass the continent’s GDP soon.

Meanwhile, Florida’s GDP is about half of Africa’s but is expanding at a pace of nearly 40% faster than Africa’s, and New York’s GDP sits at roughly 75% of the continent’s total.

Further illustrating this dynamic, Simons noted that several US states are economic peers of individual African countries.

“Iowa is the economic peer of Nigeria now (after the latter’s forex crisis). Wisconsin is at South Africa’s level. Minnesota eclipses Egypt. And Kenya is in West Virginia’s leagues.”

Bright Simons, Honorary Vice President of the IMANI Centre for Policy and Education

Although African nations like Nigeria have established some direct economic relationships with US states, such as the recent Nigeria-Texas aviation agreement, these engagements tend to be narrowly focused.

According to Simons, African countries should broaden these initiatives, diversifying the areas of collaboration beyond single industries to sectors like renewable energy, agriculture, and technology.

The perceived cultural and diplomatic hierarchy between national leaders and state officials could be a barrier to this approach.

“African countries may think it is demeaning for their Presidents to confer with a US governor on a peer basis on economic matters,” Simons observed. Nevertheless, he argued that “in economics, sometimes ego must take a backseat.”

Bright Simons’s analysis offers a new perspective on US-Africa relations, suggesting that Africa’s leaders look beyond traditional diplomatic channels and explore partnerships with individual US states.

READ ALSO: Scholz Slammed For Delaying Confidence Vote