By definition, legal education is an essential part of any country’s civic and democratic life.

In addition to preparing students to practice law, it also helps them comprehend the complex network of laws, rules, and values that regulate daily interactions, such as how neighbors and businesses interact with the government and with each other.

The situation of legal education in Ghana, however, poses a pressing conundrum: despite rising demand, access is still constrained, depressing the aspirations of many aspiring attorneys.

In light of this, the movement to democratize access to legal education is not only relevant but also necessary.

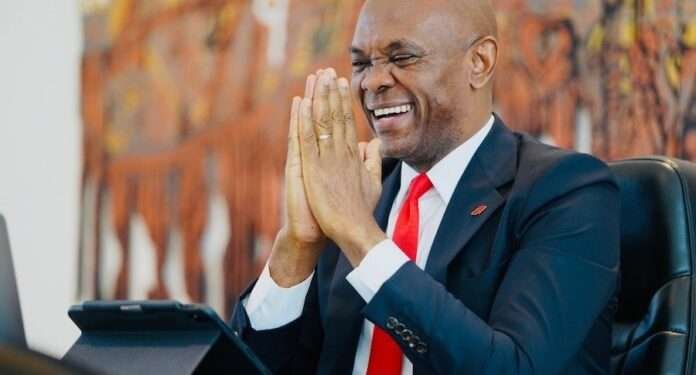

In a detailed and compelling statement, Hon. Rockson-Nelson Etse Dafeamekpor, Member of Parliament for South Dayi and a distinguished legal practitioner, has made a clarion call for a robust reform of Ghana’s legal education system.

According to him, democratising legal education is not only timely but necessary for national development and justice delivery.

“For citizens to have the full enjoyment of their civic capacities, they need some basic knowledge of at least some aspects of law. Individuals and officials who perform important roles involving the law, such as policemen, businessmen or politicians, need an understanding of parts of the law and its underlying policies and values in order to be effective at their roles.”

Hon. Rockson-Nelson Etse Dafeamekpor, Member of Parliament for South Dayi

Legal education, he noted, is the foundation of every legal system and forms a critical component of civic life, adding that it comprises structured training through coursework at law faculties, practical experience in legal aid settings, and rigorous certification via the bar exam.

This system ensures that only certified individuals can practice as lawyers, but beyond the professional track, Hon. Dafeamekpor argued, legal education plays a far greater role in any country.

He asserted that law governs every aspect of daily life—from how to interact with neighbours to how to transact business, use public roads, and even live in homes, adding that it is, therefore, in the public’s interest to make legal education accessible, not restrictive.

While regulation is necessary to preserve standards, he argued that this must not come at the expense of national progress.

British Colonial Influence

Reflecting on Ghana’s legal history, Hon. Dafeamekpor explained how the country’s dual legal system, comprised of customary law and English common law, originated from British colonial influence.

The Bond of 1844 and the Supreme Court Ordinance of 1876 introduced English legal traditions into the Gold Coast, necessitating the training of locals in the foreign system. At the time, aspiring Ghanaian lawyers had to travel to the United Kingdom to receive training.

Post-independence, Ghana sought to localise legal education. In 1958, the Legal Practitioners Act established the General Legal Council, which in turn set up the Ghana School of Law, the first in Sub-Saharan Africa.

President Kwame Nkrumah, at the school’s founding, underscored the need for lawyers educated in African political and social contexts to support state institutions, local governments, and the judiciary. His vision materialized in 1963 when the first nine lawyers graduated from the Ghana School of Law.

Despite the strides made over the decades, Hon. Dafeamekpor noted with concern that access to professional legal education remains unduly restrictive.

According to him, even though the country has made some progress in the manner it provides legal education with the increased number of lawyers in the market, the country still lags behind in meeting the adequacy of the demand.

“Professional legal education has received few innovations, leaving many who desire to acquire professional certification to practice as solicitors and barristers without the opportunity to do so”.

Hon. Rockson-Nelson Etse Dafeamekpor, Member of Parliament for South Dayi

Hon. Dafeamekpor further noted that presently, more than 25 tertiary institutions across Ghana offer Bachelor of Laws (LLB) programmes; however, these produce far more graduates than the Ghana School of Law is able to accommodate.

This bottleneck, he argued, has created a funnel effect—many qualify for law school, but few are admitted. The statistics are startling. In 2020, out of 2,763 candidates who took the entrance exam to the Ghana School of Law, only 1,045 were admitted.

In 2021, 2,824 wrote the exam, but only 790 passed. The following year, 2022, saw a drop, with just 699 out of 2,654 making the cut. In 2023, 1,964 failed to qualify, leaving only 964 admitted. For the 2024 intake, just 1,441 candidates passed out of more than 3,000 who sat for the exams.

“Ghana’s population has seen a surge in numbers. This comes with its attendant demands for increased professional services, including the services of lawyers. Institutions, both private and public, require in-house legal units to advice and guide them on decisions that have legal implications.

“This would go a long way to reduce the number of cases that are found in the law courts while leaving sufficient space for serious legal matters only to be found in our courtrooms.”

Hon. Rockson-Nelson Etse Dafeamekpor, Member of Parliament for South Dayi

Arguement for Reforms

While critics argue that expanding access could dilute the quality of legal professionals or that Ghana is already producing too many lawyers, Hon. Dafeamekpor refuted both claims.

He strongly opined that while the number of lawyers is growing, the demand for specialized legal expertise and the need for equitable access to justice across the country suggest that the legal profession needs to adapt to the evolving needs of Ghana’s economy and society faster than it currently is doing.

He pointed out that the current lawyer-to-citizen ratio in Ghana is approximately 1:5,000, far below the ideal ratio of 1:250, asserting that by that measure, Ghana is significantly under-lawyered.

On concerns about quality, he insisted that proper regulation and oversight by the General Legal Council can ensure that standards are maintained even as access is widened.

To address the issue, Hon. Dafeamekpor backed the government’s recently announced legislation to liberalise professional legal education.

He suggested that accredited university law faculties—especially public universities already offering LLB programmes—should be empowered to provide the professional law course, subject to the supervisory authority of the General Legal Council.

This model, he argued, would maintain the council’s crucial role in ensuring quality while decentralising legal training and increasing capacity.

Presently, the Ghana School of Law operates primarily from its main campus in Accra, with satellite centres at the University of Professional Studies, Accra (UPSA), the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration (GIMPA), and the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST). Yet, this setup remains insufficient to meet national demand.

According to Hon. Dafeamekpor, a forward-looking legal regime must evolve to meet 21st-century realities. He advocated for public universities already running LLB programmes to be upgraded and accredited to offer professional legal training.

“It must equally be accessible like all other professional education. As many as are willing, so long as they pass and possess the requirement, must be given the opportunity to go through professional legal education instead of putting in place impediments that cut short their dreams and desires.”

Hon. Rockson-Nelson Etse Dafeamekpor, Member of Parliament for South Dayi

Maintaining Quality of Legal Education

This would ensure broader access without compromising the quality of legal education or the integrity of the legal profession.

He emphasized that democratising legal education does not imply lowering standards; it is about ensuring that all qualified individuals are given a fair chance.

Legal education, he asserted, must be viewed as a right and not a privilege. It must be accessible to all who meet the criteria, not hindered by outdated, restrictive systems that no longer serve the needs of a rapidly developing society.

In conclusion, Hon. Dafeamekpor’s argument is clear: legal education must keep pace with the needs of the nation. Ghana’s legal system needs more professionals—well-trained, ethically grounded, and geographically dispersed—if it is to serve its citizens effectively.

For him, legislative reforms to decentralize and democratize access to professional legal education will not only bridge the lawyer-to-citizen gap but will also support economic development, institutional accountability, and a stronger rule of law.

READ ALSO: Expert Calls for Strengthening DMCs to Improve Small-Scale Mining Governance