For years, Ghana’s Free Senior High School (Free SHS) policy has been at the centre of political discourse, with both praise and criticism shaping the narrative of its implementation.

Civil society organizations, education policy experts, and concerned citizens have consistently raised concerns about the long-term sustainability and equity of the policy.

While the initiative was launched as a means of breaking financial barriers to secondary education, its financing model appears to be exacerbating economic inequalities rather than resolving them.

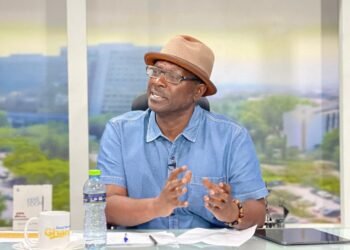

Kofi Asare, the Executive Director of Africa Education Watch (Eduwatch), has been at the forefront of such critiques, challenging the notion that the Free SHS policy has entirely removed financial obstacles for the poor.

According to him, ardent defenders of the policy—whom he refers to as “Free SHS deity worshippers”—often misquote his analyses to justify their unwavering support.

He clarified that the policy has not removed all financial barriers for poor families but has only alleviated some, leaving substantial out-of-pocket costs that disproportionately burden low-income parents.

“For the government to spend the same amount of money on both rich and poor in SHS, in the face of significant out-of-pocket expenses due to inadequate financing of a free SHS policy that seeks to remove financial barriers to access by the poor, the policy essentially ends up subsidizing secondary education for the rich than makes secondary education free for the poor.”

Kofi Asare, Executive Director of Africa Education (Eduwatch)

Mr Asare further cited Eduwatch’s cost incidence analysis of the Free SHS policy from 2017 to 2022 revealing a striking disparity in expenditure.

The report found that, on average, government spending per student under Free SHS was GH¢1,241 annually, covering only 23% of the total cost. Parents, on the other hand, were responsible for GH¢4,185 annually—77% of the total expenses.

For Mr Asare this contradicts the policy’s fundamental goal of eliminating financial barriers for the poor, as those from lower-income backgrounds continue to struggle with affordability.

“Now, let’s assume two parents at Presec in 2024. Both spent 5k on boarding prospectus and 1k on feeding support due to poor financing of feeding. Their total expenditure is 6k. Parent 1 earns within a higher income quintile of say GHC 12k a month, while Parent 2 earns within a lower income quintile of GHC 2k a month”.

Kofi Asare, Executive Director of Africa Education (Eduwatch)

This stark contrast raises a fundamental question: who bears the greater financial burden? Kofi Asare emphasized that by subsidizing education equally for both rich and poor households without considering disparities in income levels, the policy inadvertently benefits wealthier families while placing poorer households in a more precarious financial position.

Free SHS: a Subsidy for the Affluent

In essence, Free SHS, as currently implemented, functions more as a subsidy for the affluent than as a lifeline for the underprivileged.

The core issue is that the policy was not designed to remove “some” financial burdens but rather the financial burden of secondary education for the poor. Yet, due to inadequate financing, the intended relief remains elusive for many low-income families.

This realization aligns with the perspectives of prominent education experts like Prof. Kwame Acheampong, who share similar concerns about the policy’s shortcomings.

The way forward requires reevaluating Free SHS’s financing model. The government must consider a means-tested approach that ensures financial support is tailored to those who need it most.

Instead of distributing resources uniformly across all economic classes, a more progressive model—where wealthier families contribute more while low-income families receive greater subsidies—would create a fairer and more sustainable system.

In its current form, Free SHS is a well-intended policy trapped in the pitfalls of poor execution. While it has expanded access to secondary education, it has not eliminated financial barriers, particularly for the poor.

As Kofi Asare rightly asserted, Free SHS was not designed to remove just “some” financial barriers for the poor—it was supposed to eliminate “the” financial burden entirely.

Until the policy is restructured to align with this fundamental goal, the claim that Free SHS has made secondary education “free” remains, at best, a half-truth.

The time has come for policymakers to move beyond ideological worship of Free SHS and engage in honest, evidence-based discussions about its real impact.

Until policymakers acknowledge and address these inequities, the program will continue to function more as an elite subsidy rather than a genuine poverty alleviation tool.

If the objective is truly to support poor students, then reform is not an option—it is a necessity.

READ ALSO: Experts Urge Government to Prioritize Solar Energy Solutions