In Ghana, post-regime accountability is a predictable yet ineffective ritual.

With each change of government, leaders vow to expose corruption, punish culprits, and recover stolen funds. Yet, the cycle of scrutiny, selective prosecutions, and inaction persists.

Accordingly, Democracy and Development Fellow at CDD-Ghana, Prof. Stephen Kwaku Azar Asare, has argued that this cycle has never led to meaningful accountability.

According to him, opposition leaders campaign on accountability, and the people elect them expecting swift action, pointing out that past administrations have all faced scrutiny from their successors.

“From the John Agyekum Kufuor administration holding the Jerry John Rawlings government accountable to the John Evans Atta-Mills administration being pressured to investigate John Agyemang Kufuor’s tenure, to the Nana Addo Dankwah Akufo-Addo administration going after John Dramani Mahama’s government, history repeats itself.

“Now, the John Dramani Mahama administration faces similar calls to reckon with its predecessors”.

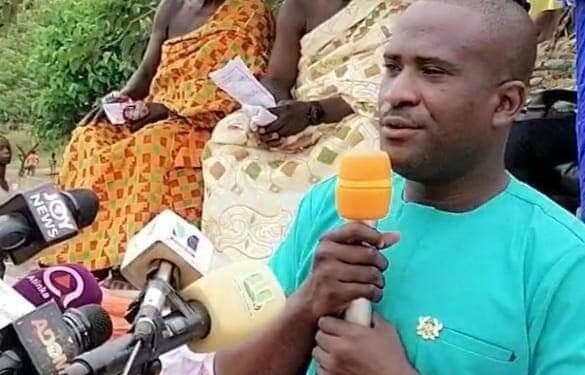

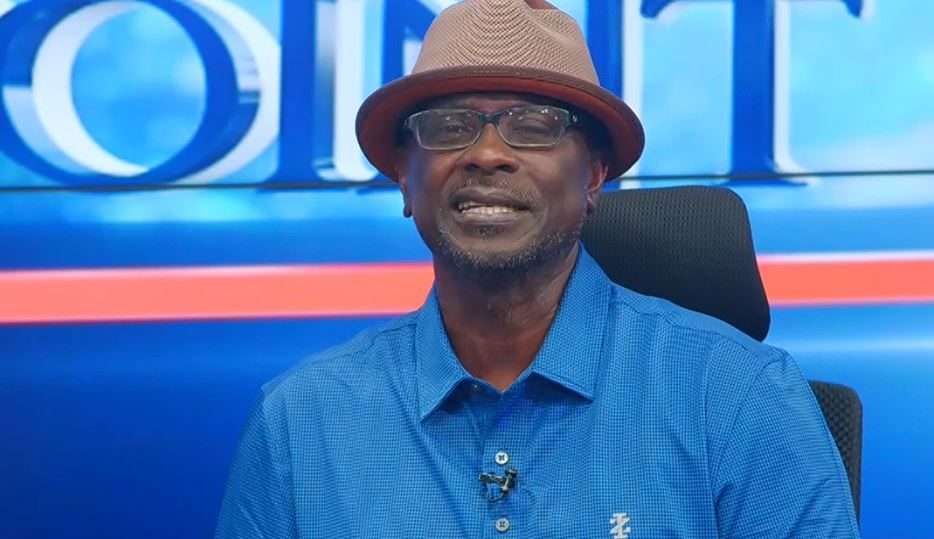

Prof. Stephen Kwaku Azar Asare

The latest call for accountability is now directed at the Akufo-Addo administration, with expectations that a new government will take action. Yet, as Prof. Asare indicated, failing to deliver on this mandate can be politically costly.

He indicated that looting of public assets by politicians remains a rational choice because the benefits far outweigh the risks.

As such, he lamented the fact that “mansions, offshore accounts, and political influence come instantly”, while consequences are rare and often delayed.

According to Prof. Asare, looters understand that the chances of facing real consequences are minimal.

He indicated that few individuals, if any, are ever prosecuted, making post-regime accountability more of a spectacle than a genuine effort to enforce justice.

The legal system itself, he stated, is structured to delay cases, allowing corruption trials to drag on for years due to constant adjournments, appeals, and procedural loopholes. As a result, justice remains elusive.

Prof. Asare lamented that looters also control the public narrative, alleging that with the backing of political loyalists and media allies, they frame accusations as political witch-hunts, making it difficult for accountability efforts to gain traction.

According to him, cultural and institutional factors further weaken the enforcement of accountability on previous governments.

This, Asare noted, causes many citizens to believe public officials deserve to “enjoy their cocoa season,” and those who refuse to engage in corruption are often ridiculed as naïve or incompetent.

Additionally, traditional and religious leaders quietly intervene, pleading for leniency on behalf of corrupt officials.

Asasre noted that these behind-the-scenes efforts dilute the momentum for justice and make it harder to hold looters accountable.

Public fatigue further compounds the problem. While initial demands for accountability are strong, interest quickly fades once a few arrests are made.

This loss of momentum, he emphasized, allows most culprits to escape scrutiny, ensuring the cycle of corruption continues.

According to him, ultimately, post-regime accountability is not a deterrent.

Prof. Asare described it as a “de minimis tax on looting, not an obstacle to it”, stating that as long as corruption remains profitable and lightly punished, officials will continue to engage in it.

Solution for Within-Regime Accountability Highlighted

Furthermore, Prof. Stephen Kwaku Azar Asare stressed that the only way to break the cycle of looting is to enforce accountability while officials are still in office.

To achieve this, he proposed governance reforms centered on OPAL (Ongoing Public Accountability & Liability), OMAMPAM (Ongoing Monitoring and Mandatory Public Accountability Measures), and OSOSOE (Oversight System for State-Owned Enterprises).

According to him, OPAL ensures real-time transparency, oversight, and enforcement during a government’s tenure.

He emphasized that the Auditor-General must actively exercise its surcharge and disallowance powers to prevent financial mismanagement before it escalates.

Similarly, OMAMPAM enforces continuous monitoring of public officials, ensuring misconduct is detected and addressed before it develops into large-scale corruption.

Asare also highlighted the importance of OSOSOE in imposing strict oversight on State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), preventing them from being exploited as channels for corruption.

He stressed that SOEs must operate as efficient and transparent institutions rather than serving as political tools for illicit financial gain.

He further called for “swift and uncompromising justice,” insisting that corruption trials must not exceed two months.

“No more endless litigation, no frivolous adjournments, no protracted appeals,” he asserted, urging the Rules of Court Committee to consider a final judgment regime to streamline legal proceedings and eliminate unnecessary delays.

“This promotes judicial efficiency by limiting appeals to only the final decision, avoiding unnecessary delays and multiple appeals on interlocutory rulings; Investigations must be completed before prosecution begins; Special anti-corruption courts must deliver verdicts swiftly; Court proceedings must be public and transparent”.

Prof. Stephen Kwaku Azar Asare

Asare stressed that prevention must take precedence over recovery, maintaining that if government officials know that they are being monitored in real time and will be held accountable immediately, the incentive to loot public resources diminishes significantly.

Corruption cases must be thoroughly investigated before prosecution begins. This will prevent unnecessary court delays and increase the chances of successful convictions.

Accordingly, Asare suggested that special anti-corruption courts should be established to handle corruption-related cases with urgency and transparency.

Court proceedings, he indicated, must be made public to ensure accountability and deter future wrongdoing, stressing that radical transparency must be enforced in government transactions.

Prof. Asare and the GOGO (Good Governance) movement stand for transparency, accountability, and value for audit.

He stated that while post-regime accountability remains necessary when within-regime measures fail, the ultimate goal must be to prevent corruption from happening in the first place. “Where there is no looting, there is no need for loot recovery.”

As such, he stressed that it is time to choose OPAL over ORAL, OMAMPAM over patronage, and OSOSOE over SOEs as political tools.

Probity must take precedence over political spectacle. Ghana’s governance system must be restructured to make corruption an unattractive and high-risk venture for public officials.

Only then can the country break free from the cycle of looting, selective justice, and unfulfilled accountability promises.

READ ALSO: Kendrick Lamar Performs at Super Bowl Halftime Show