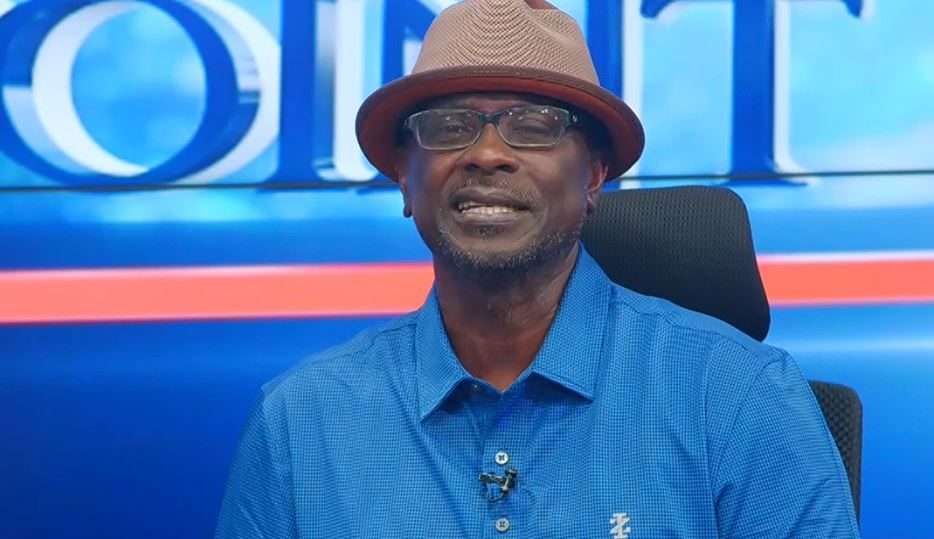

Justice reform has moved to the forefront in Ghana, with Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare, a legal expert and Democracy and Development Fellow at CDD-Ghana, unveiling a bold new proposal known as Kofi Brokeman’s Section 35.

This initiative aims to address a glaring imbalance in Ghana’s criminal justice system, offering a more humane approach to petty, non-violent offenses committed by economically vulnerable citizens.

According to Prof. Asare, while Ghana’s criminal justice system enforces laws that are technically sound, it often fails to deliver true justice for the nation’s poorest citizens.

He pointed out that Section 35 of the Courts Act, 1993 (Act 459), currently allows individuals charged with economic crimes against the State to offer restitution rather than face imprisonment.

However, he lamented the absence of a similar provision for those who commit minor offenses out of desperation and poverty.

“Consider the case of a poor person who steals plantains to feed their family. The act is undoubtedly unlawful, but it differs fundamentally in motive, impact, and scale from white-collar crimes that drain public resources.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

Prof. Asare pointed out that, unlike high-level economic crimes that deplete national funds, these petty offenses neither harm the State nor involve violence, yet the offenders often endure severe legal consequences.

He emphasized that such individuals typically suffer harsher penalties than white-collar criminals, facing prolonged pre-trial detentions, rapid convictions, limited legal representation, and the long-term stigma of criminal records.

These outcomes, according to Prof. Asare, trap individuals in an unending cycle of poverty and incarceration, undermining the moral integrity of the justice system. “Justice must reflect not only equality before the law but also equity in its application.”

To address this inequity, he has proposed the creation of Section 35A—informally referred to as the “Kofi Brokeman Law“—designed to offer restorative justice for low-value, non-violent offenses committed by indigent individuals.

A Restorative Approach To Justice

At the heart of this proposed justice reform is a framework that emphasizes accountability without unnecessary incarceration.

The “Kofi Brokeman Law” allows offenders to acknowledge their wrongdoing and offer symbolic or practical reparations, such as apologies, community service, or other forms of non-custodial remedies, rather than face imprisonment.

Prof. Asare outlined multiple benefits to this approach. It would humanize the justice system by treating poverty-driven crimes as social issues rather than moral failings.

In addition, it would alleviate prison overcrowding by diverting petty offenders into alternative sanctions, promote reintegration by sparing individuals from acquiring permanent criminal records.

This, according to Prof. Asare, will ultimately conserve state resources that would otherwise be spent prosecuting and incarcerating the economically vulnerable.

“Ultimately, the proposal affirms that our laws must punish wrongdoing, but they must also distinguish between corruption and desperation,” he said, stressing the importance of separating white-collar corruption from survival-driven crimes.

“Where a person is charged with a non-violent offence involving the appropriation or attempted appropriation of low-value property, and the act did not result in economic loss, harm, or damage to the State or any State agency, the accused may inform the prosecutor whether the accused admits the offence and is willing to offer an apology, symbolic reparation, or undertake a community-based remedy in lieu of custodial punishment.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

He noted that upon receiving such an offer, prosecutors would evaluate its suitability based on the nature of the offense, the offender’s personal circumstances, and overall considerations of justice.

Prof. Asare emphasized that if the prosecutor finds the offer appropriate, the case would proceed to the Court, where a final determination would be made.

Courts To Play Supervisory Role in Justice Reform

Moreover, Prof. Kwaku Asare indicated that the Courts, under the proposed law, would assume an essential supervisory role in implementing the justice reform.

According to him, if the Court finds the offer of apology, reparation, or community-based remedy just and proportionate, it would accept a guilty plea and convict the accused based on that plea.

He noted that instead of passing a custodial sentence, the Court would then issue an order for the execution of the agreed-upon remedy.

Remedies under this system could include a formal apology to the complainant or community, symbolic restitution equivalent to the value of the stolen item, unpaid community service for a specified period, or participation in rehabilitation or reintegration programs.

These measures are designed to rehabilitate rather than punish, allowing offenders to repair their wrongs while remaining active and productive members of society.

However, Prof. Asare clarified that the system is not without enforcement measures.

“Where the person fails to comply with the Court’s order without reasonable excuse, the Court may revoke the non-custodial remedy and proceed to impose an alternative sentence, taking into account the accused’s efforts at compliance.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

Prof. Asare believes that this justice reform proposal is not merely a legal innovation but a moral imperative.

He contended that Ghana’s legal framework must evolve to recognize the distinction between criminal acts driven by corruption and those born out of desperation and poverty.

As Ghana struggles with the persistent challenges of overcrowded prisons, insufficient legal representation, and widening economic disparities, the need for comprehensive justice reform becomes increasingly urgent.

Proposals such as “Kofi Brokeman’s Section 35” present a forward-thinking solution that could transform the justice system into one that balances fairness with compassion while addressing the root causes of poverty-driven crime.