Swearing in the Speaker of Parliament as Acting President when both the President and Vice-President are abroad is a misstep in constitutional interpretation, according to a leading legal expert.

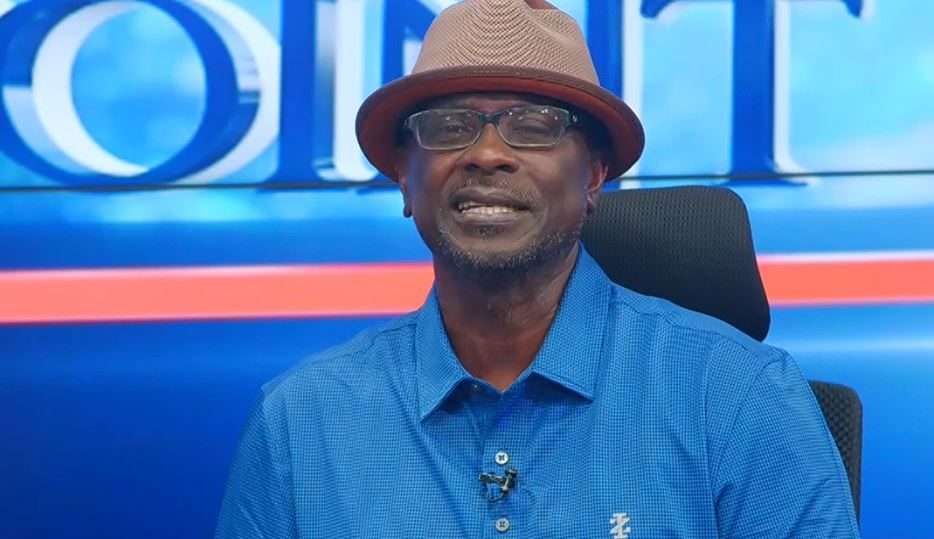

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare, a Democracy and Development Fellow at CDD-Ghana, has strongly criticized the long-standing practice of swearing in the Speaker whenever the top two executives are out of the country.

He called it a “constitutional folly,” asserting that this widely accepted procedure is based on a flawed understanding of Ghana’s legal framework.

In an extensive legal argument, Prof. Asare stated that this practice, while appearing routine, is legally unfounded and constitutionally dangerous.

He traced the origin of this misinterpretation to a Supreme Court ruling in Asare v. Attorney-General [2003–2004] SCGLR 823, which, in his view, misapplied the constitutional text.

“Let’s be clear: the 1992 Constitution does not require the Speaker of Parliament to be sworn in when the President and Vice-President are both simply outside Ghana. That ritual is not law—it is theatre.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

Prof. Asare explained that the source of this confusion lies in Article 38(3) of Ghana’s 1969 Constitution. That clause explicitly allowed the Speaker to step in when the President was abroad.

However, that document was rooted in the Westminster system, where the President was a ceremonial figure, the Prime Minister held real power, and the Speaker, often from the ruling party, could step in without political disruption.

By contrast, Ghana’s 1979 and 1992 Constitutions established an executive presidency, fundamentally changing the framework of authority.

In this new structure, the President exercises full executive power, and the Constitution clearly outlines when and how that power can be temporarily transferred.

According to Prof. Asare, Article 60 of the 1992 Constitution directly states that when the President is absent from Ghana, the Vice-President assumes presidential responsibilities.

This article ensures continuity without transferring power outside the executive branch.

Constitutional Clarity Challenges Old Assumptions

Furthermore, Prof. Asare highlighted that constitutional interpretation must evolve with the nation’s governing framework.

He emphasized the deliberate shift in the 1992 Constitution away from earlier ceremonial roles to clear executive authority structures.

He cited Article 60(11), which dictates that the Speaker only acts when both the President and Vice-President are unable to perform their duties—not when they are simply abroad.

He emphasized that this clause omits the phrase “absent from Ghana,” and that omission is critical.

“The framers clearly distinguished between ‘absence from Ghana’ and ‘inability to perform.’ The former is routine and expected. The latter is serious—death, resignation, illness, or incapacitation.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

Despite this textual precision, Justice Date-Bah, in earlier judicial commentary, adopted a “purposive interpretation” of the Constitution—arguing that being abroad equates to being unable to govern.

Prof. Asare denounced this approach as a regression to outdated legal frameworks, accusing the courts of importing provisions from the obsolete 1969 Constitution.

“He could not rely on subjective purpose, because the framers never intended this absurdity, so he invoked ‘objective purposive interpretation’: the view of a hypothetical reasonable observer.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

He challenged the logic of this approach by asking: “What reasonable person believes that a President traveling abroad is automatically incapable of governing?”

In an era of instant communication and mobile governance, Prof. Asare believes such an assumption is both outdated and dangerous.

Temporary Speaker Role Risks Executive Overreach

Moreover, Prof. Asare cautioned that the consequences extend beyond mere theory. When the Speaker is sworn in as Acting President during such absences, they are effectively granted full executive powers.

This could potentially pave the way, however improbable, for drastic actions like reversing appointments or nullifying key decisions, all triggered by a temporary and largely symbolic role.

“The law is about structure, not just trust. That’s why the Constitution requires both inability and vacancy—not mere travel—for such drastic transitions.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

Prof. Asare summed up the situation with sharp criticism: the Constitution is unambiguous, but poor judicial interpretation has created unnecessary and risky precedents. “There is no ‘Kotoka clause’ in the Constitution.”

Calling the prevailing interpretation “expired aspirin,” he warned that outdated legal reasoning, like expired medication, is dangerous when swallowed by a constitutional democracy.

In closing, he called for a return to constitutional fidelity.

“Let the Constitution breathe. Let the Vice-President act. And let the Speaker stay in his lane, unless the nation truly needs him to cross over.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

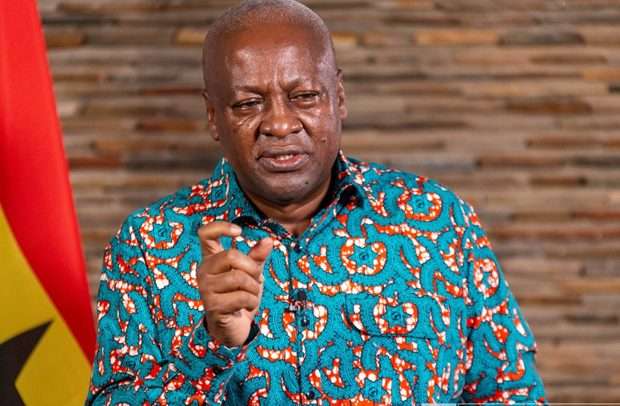

His comments came in response to the Minority in Parliament, who recently accused the government of violating the Constitution by failing to swear in the Speaker while both the President and Vice-President were out of the country—along with the subsequent absence of the Speaker himself.

Prof. Asare’s message was unequivocal: Ghana’s democracy has no need for ceremonial stand-ins disguised as constitutional requirements.

According to him, both the President and Vice-President retain the ability to govern, even while abroad. The law is already clear—what’s needed is a forward-looking interpretation, not a reliance on outdated precedents.

READ ALSO: Trump Hints Sanctions Removal On Syria