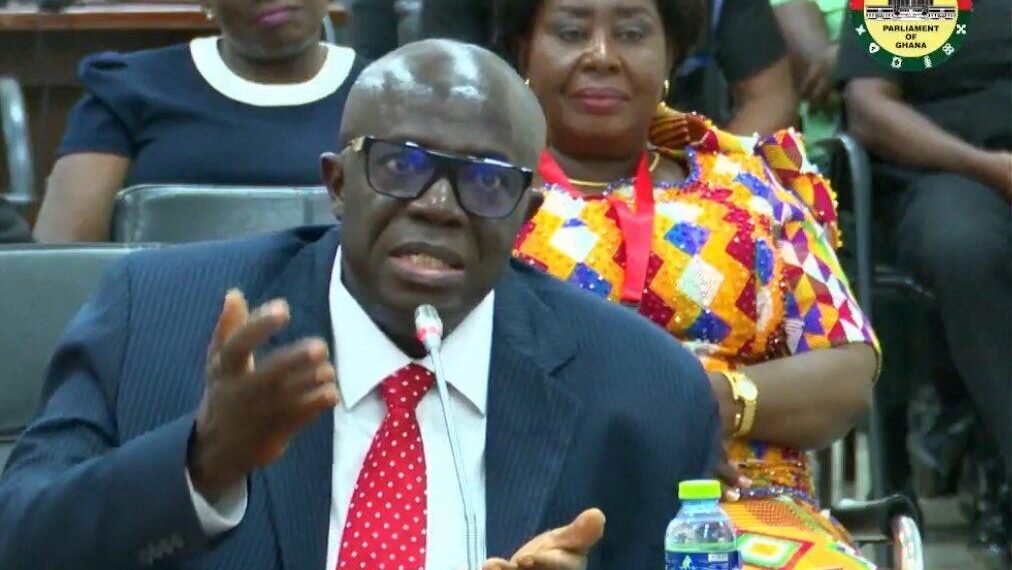

A Supreme Court Nominee, Sir Dennis Dominic Adjei, JSC, has called for comprehensive and careful reforms of citizens’ participation in Ghana’s justice administration, particularly focusing on the efficacy and future of the jury and assessor systems.

His insights, drawn from extensive experience and evident scholarly consideration, painted a picture of a system ripe for reform, yet retaining fundamental importance for fostering public trust and engagement in the rule of law.

The nominee’s thoughtful answers highlighted both the challenges and the inherent value of Article 125(2) of the Constitution, which champions popular involvement in justice through such institutions.

The line of questioning, initiated by a Member of Parliament, probed the nominee’s views on the practical application of Article 125(2), specifically against observations of individuals seemingly becoming “professional” assessors or jurors.

The MP sought to understand whether this system, fraught with such concerns, should be maintained, re-evaluated policy-wise, or advised upon for a new direction.

Sir Dennis Dominic Adjei embraced the query with a comprehensive response, revealing his profound engagement with the subject matter, a topic on which he admitted to having “a lot of thesis.”

The nominee immediately delved into the systemic issues plaguing the current jury process. He pointed out the existing qualifications—requiring individuals to be between 25 and 60 years old and capable of speaking English—but then exposed a stark reality on the ground.

According to him, his inquiries at various institutions had revealed a concerning practice: individuals perceived as “troublesome” or those for whom no other duties were available were sometimes dispatched to serve as jurors or assessors, indicating a fundamental misunderstanding or misuse of the system.

Peer-to-Peer Hearing

Sir Dennis Adjei emphatically stated that the true essence of a jury trial, a “peer-to-peer hearing” and a fundamental “role to your nation building,” was being diluted.

He lamented the transformation of jury service into a perceived “profession,” recalling his own experience as President of Magistrates in the Ashanti Region, where he had resisted such professionalisation, insisting on term limits—a maximum of two years—for service.

He even recounted an instance where professional assessors had attempted to appoint a “dean,” a concept he dismissed as illegitimate, given that jury service is not an office.

Sir Dennis Adjei articulated the core problem as a lack of appreciation for the jury system’s true purpose.

He highlighted instances where, despite a judge’s careful summing up, jurors might deliver verdicts—convictions or acquittals—that were entirely unanticipated and, at times, lacked clear justification when cases proceeded to appeal.

While acknowledging the inherent challenge this presents, he noted Ghana’s crucial advantage: the right to appeal against jury rulings, which provides a vital safety net against potentially flawed decisions.

Given these observations, his conclusion was resolute: the system, as it currently operates, “doesn’t help,” and therefore, “we need to reform it.”

Despite his strong critique and call for reform, Sir Dennis Adjei did not advocate for the outright abolition of the jury system, offering a carefully considered view: “We may continue to have it.”

His reasoning centred on the fundamental principle of “citizens’ participation,” emphasising its role in helping the populace understand the judicial process and the distinct roles of judges versus the citizenry.

He posited that exposure to the legal system through jury service could deter individuals from resorting to “instant justice” on the streets, thereby reinforcing adherence to the rule of law.

However, he also introduced a pragmatic caveat: if empirical evidence were to demonstrate that the system had “outlived its relevance,” a re-evaluation under Article 125(2) would be justified.

Expansion of Citizen Participation

Expanding on the broader concept of citizen participation in justice, Sir Dennis Adjei seamlessly linked the discussion to Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) mechanisms.

He highlighted how ADR avenues, such as mediation, conciliation, and customary arbitration, also embody the spirit of Article 125(2) by involving non-judges in dispute resolution.

This perspective underscored his comprehensive understanding of how diverse mechanisms can contribute to accessible and effective justice delivery outside the traditional courtroom, aligning with the constitutional mandate for popular involvement.

READ ALSO: Iran-Israel Tensions Could Trigger Fuel Price Hikes – IES Warns