For anyone trying to follow protest movements around the world it is hard to keep up. Large anti-government demonstrations, some peaceful and some not, have taken place in recent weeks in places on every continent: US, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, Mali, Ivory Coast, Britain, Lebanon with the latest high profile protest being the ENDSARS protests in neighbouring Nigeria.

Nine years ago, beginning in Tunisia, a series of street protests across the Middle East turned the region upside down and became known as the Arab Spring. At times in these past few weeks, it has seemed as if something similar was unfolding across the world as we are seeing constant strikes, marches and riots in various countries.

A person’s right to air grievances without fear of retribution or censorship is fundamental to democracy and has been enshrined in many constitutions of democratic countries.

Experts have found that political protests are caused by a strange combination of factors including dashed expectations, rising inequality, persistent corruption and a deep sense of frustration. Protesters around the world have been calling for police reform and an end to systemic racism.

In Philippines, Protesters took to the streets over a new anti-terror bill. The Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020, which was heavily pushed by President Rodrigo Duterte, would broaden the definition of terrorism and give police additional arrest and surveillance powers.

In the US, the killing of George Floyd and shooting of Jacob Blake sparked or re-sparked the worldwide Black Lives Matter Campaign with protests in several countries calling for police reforms.

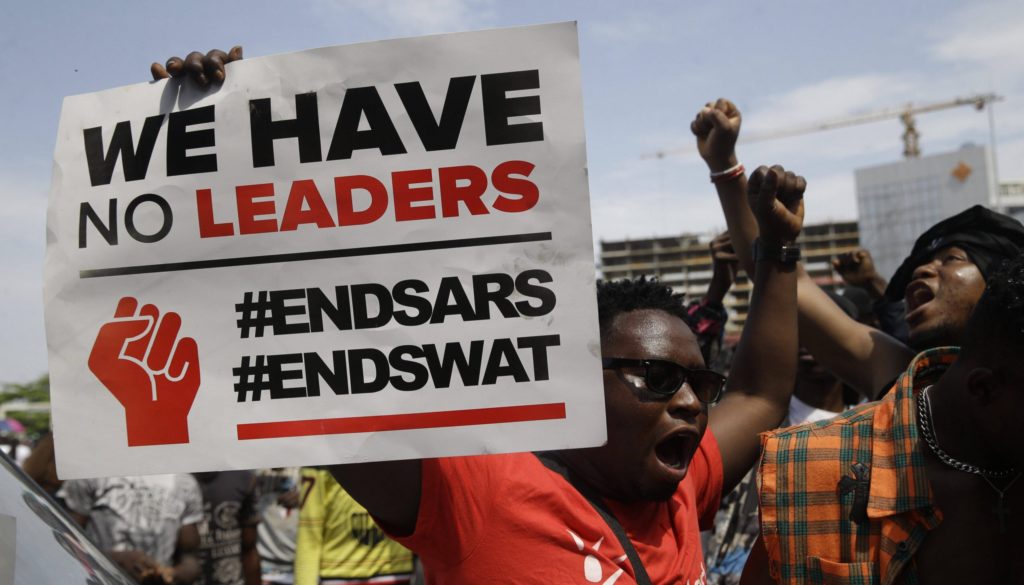

Also for the past two weeks, Nigeria has been rocked by protests that erupted against police violence and evolved into broader anti-government demonstrations, leading to a deadly crackdown.

The protestors sometimes achieve their mission and get the change wanted but the downside to this is protests also take lives. In Algeria for instance, they managed to get a president who had been in power for more than 20 years to step down. In Iraq, the prime minister resigned at the cost of 400 lives. In Nigeria, the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (Sars) has been disbanded, but not without 59 fatalities.

Several cities have reported violence against protesters, and many have imposed curfews and boarded up businesses following accounts of looting all evident in Nigeria’s recent ENDSARS campaign.

Experts have also found a trend running across the recent protests; they are led by young people. And the common theme is injustice, basically – government corruption, unemployment, poverty, lack of government services. The youth are said “to have this rage against the traditional political class.”

These findings are in line with a recent study by the Cambridge University’s Centre for the Future of Democracy which has ascertained that “Young people are less satisfied with democracy and more disillusioned than at any other time in the past century, especially in Europe, North America, Africa and Australia.”

The study adds that a majority of the world’s young people may “now be dissatisfied with the political system.”

“This democratic disconnect is not a given, but the result of democracies failing to deliver outcomes that matter for young people in recent decades, from jobs and life chances to addressing inequality and climate change,” said Dr. Roberto Foa, a Cambridge University professor in politics and lead author of the report, in a statement.

The distrust in democracy, the researchers said, is linked largely to “economic exclusion”-specifically employment rates for young people and inequality. Studies have found significant gaps in wealth between Millennials and older generations, a key factor in these findings.

“Higher debt burdens, lower odds of owning a home, greater challenges in starting a family, and reliance upon inherited wealth rather than hard work and talent to succeed, are all contributors to youth discontent,” said Dr Foa.

“Right across the world, we are seeing an ever-widening gap between youth and older generations on how they perceive the functioning of democracy,” he added.

Kenyan academic and author, Nanjala Nyabola, offers a different explanation: “Democracy is hard,” she said during a discussion on how Brexit can affect third world countries. “It requires constant vigilance – something that we now see is difficult to achieve even under the most ideal circumstances.”

“For many, life is already a soul-sapping constant struggle to put food on the table and keep a roof over one’s head. In such circumstances, constant popular engagement with the issues of the day as well as keeping an eye on what the state and political elite get up to, as is necessary for any democracy to thrive, seem onerous. So voters take short-cuts which include relying on someone else to tell them what is going on in the democratic kitchen.

“Whether they take their cues from politicians, journalists or other self-appointed experts, one risk is the electorate may not know when they are being misled, as many say was the case with Brexit. But then again, voters may not care.”

Ilya Somin, a professor of law at George Mason University, adds that political supporters tend to behave very much like sports fans, less interested in the merits of arguments or how well the game is played than in whether their side wins.

“If voters do not care about politics, why do they even bother to vote? Much like going to a football game and cheering for your favourite team, voting allows people the vicarious satisfaction of participation without the hard work of getting onto the field and wrestling with the issues. And like their sports teams, many voters rarely pick political teams based on their ideas rather than on arbitrary considerations such as ethnicity or place of birth. If your family and neighbours vote for a particular side, the likelihood is so will you.”

With a number of leaders across the African continent especially, adjusting their constitutions to increase the number of times they can legally run for office, to the crackdown on peaceful protestors, to the abuse of citizens by police who are supposed to protect them, to the “successful” Coup D’état in Mali, it raises the questions; how sustainable is democracy and what is the way forward?

Echoing public philosopher, Roman Krznaric’s view, “when politicians fail to look beyond the next election they are neglecting the rights of future generations” and it certainly looks like Millennials are ready to rise up.