The Ugandan government intends to introduce a law to allow military tribunals to try civilians for certain offences even after the practice was banned by the Supreme Court.

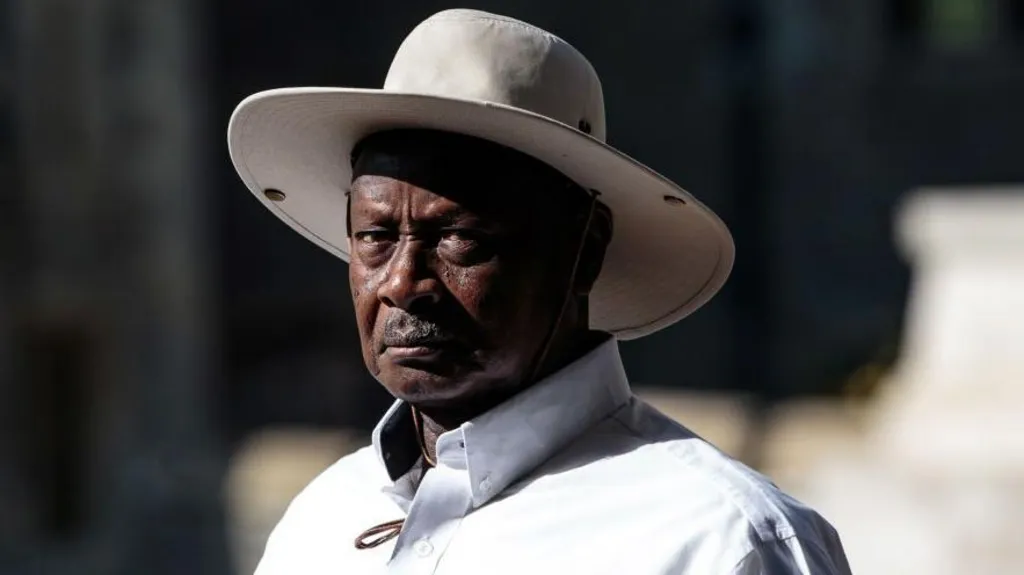

Human rights activists and opposition politicians have long accused President Yoweri Museveni’s government of using military courts to prosecute opposition leaders and supporters on politically motivated charges. The government denies the accusations.

In January Uganda’s Supreme Court delivered a ruling that banned military prosecutions of civilians, which forced the government to transfer the trial of opposition politician and former presidential candidate Kizza Besigye to civilian courts.

If successfully enacted, the new law could allow the government to take Besigye back to a military court martial.

The law has been drafted and is awaiting cabinet approval before it is introduced in parliament, Nobert Mao, the minister for justice and constitutional affairs, told parliament late on Thursday.

The law will define “exceptional circumstances under which a civilian may be subject to military law”, he said.

Besigye, a veteran political rival of Museveni, has been in detention for nearly five months on what his lawyers say are politically motivated charges.

Besigye’s Legal Woes

Kizza Besigye’s legal battles, emblematic of Uganda’s stifled democracy, began in earnest in 2005 when he returned from exile to challenge President Yoweri Museveni, his former ally during the 1981–1986 bush war. His first treason charge that year — accused of plotting to overthrow the government — set the tone for a two-decade campaign of judicial harassment.

Despite scant evidence, the state pursued the case, a pattern repeated in 2016 when Besigye was charged after symbolically declaring himself “people’s president” following a disputed election. These accusations, often dismissed by courts for lack of proof, underscore what Amnesty International condemned as politically motivated repression.

Besigye’s four presidential bids (2001–2016) were met with state violence. During the 2011 “Walk to Work” protests against economic hardship, security forces arrested him over 30 times, deploying tear gas and live ammunition to disperse supporters.

In 2016, police besieged his home for months, effectively detaining him without charge — a tactic Amnesty decried as a violation of due process. Such methods extended to his party, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), whose offices were raided and members arrested to obstruct legal challenges to election results.

The government’s brutality escalated in November 2024 when Kenyan authorities abducted Besigye during a book launch and renditioned him to Uganda. Charged in a military court with treason and illegal firearms possession, he faced the death penalty until a landmark Supreme Court ruling in January 2025 barred civilian trials in military courts.

Transferred to a civilian court, Besigye appeared emaciated from a hunger strike protesting his detention, a scene that galvanized public outrage. Prosecutors, however, simply revised the charges — the third such alteration — to allege he sought foreign support to topple Museveni, again relying on nebulous evidence.

Opposition figures beyond Besigye endure similar repression. In 2016, FDC leaders were routinely arrested to block election petitions, while today, activists aligned with newer groups like the National Unity Platform (NUP) face arbitrary detention. Besigye’s co-accused, aide Obeid Lutale and army officer Denis Ola, reflect the regime’s broadening targets. Even the judiciary, as Besigye noted in a 2016 letter to Uganda’s Chief Justice, has been weaponized to legitimize persecution.

International actors, including Besigye’s wife Winnie Byanyima (UNAIDS director), condemn these abuses as violations of human rights law. Yet Museveni’s regime persists, leveraging legal loopholes and force to silence dissent. With Besigye’s health deteriorating and the 2026 elections approaching, Uganda’s opposition faces a precarious future — one where resilience is tempered by the relentless grind of state repression.