A vaccination might be the next significant development in the fight against cancer. Researchers claimed that, they have reached a turning point in their work, after decades of patchy progress, and many trust vaccination would be available in five years.

Instead of conventional vaccines that shield against sickness, there will be doses that reduce tumor size and halt the spread of cancer. With the progress revealed this year for lethal skin disease melanoma and pancreatic cancer, these experimental treatments have shown to be effective against breast and lung cancer.

“We’re getting something to work. Now we need to get it to work,” Dr. James Gulley, Co-director of National Cancer Institute, said.

However, scientists have discovered how cancer conceals the body’s defense system. Similar to other immunotherapies, cancer vaccines help the immune system to detect and eliminate cancer cells by boosting it. Additionally, several recent ones make use of mRNA, a substance first utilized in COVID-19 vaccinations but later produced for the treatment of cancer.

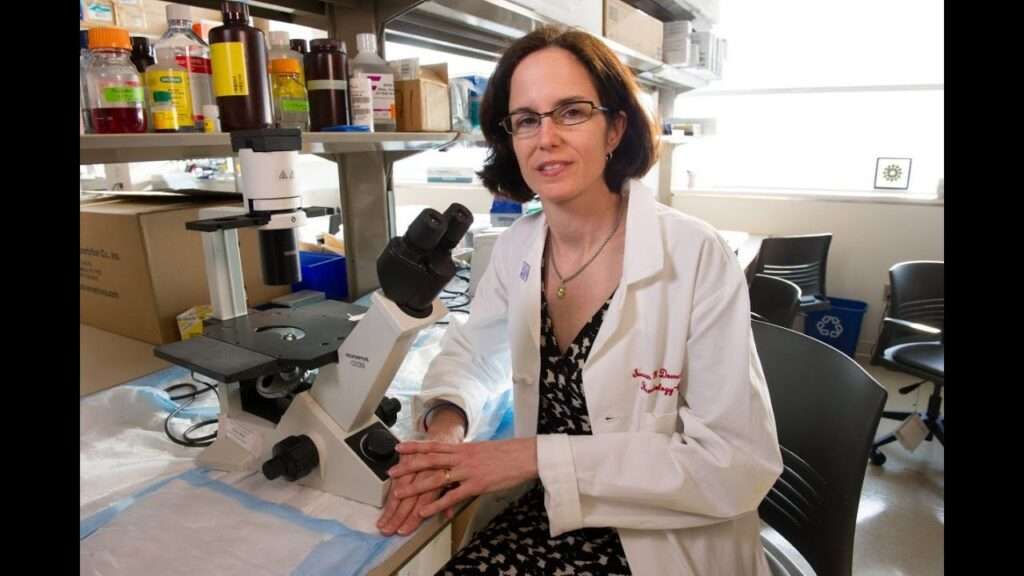

According to Dr. Nora Disis of the Cancer Vaccine Institute at UW Medicine in Seattle, for a vaccine to be effective, it must instruct the immune system’s T cells to regard cancer as harmful. T cells, once developed, can move everywhere in the body in search of threat.

“If you saw an activated T cell, it almost has feet. You can see it crawling through the blood vessel to get out into the tissues,” she said.

The development of therapeutic vaccines has been proven difficult. The first, Provenge, was licensed in the United States in 2010, to treat advanced prostate cancer. It entailed preparing a patient’s own immune cells in a lab and administering them via IV. Treated vaccinations are also available for early bladder cancer and metastatic melanoma.

According to Olja Finn, a vaccine researcher at the University Of Pittsburgh’s School Of Medicine, early cancer vaccine research failed, because cancer defeated and outlasted patients’ weakened immune systems. “All of these trials that failed allowed us to learn so much,” Finn said.

Moreover, since the experimental vaccines were ineffective for people with more severe disease, Finn has now concentrated on those with early disease. Her team is developing a vaccination research in women with ductal carcinoma in situ, a low-risk, noninvasive breast cancer.

More cancer-prevention vaccines may also be on the way. Hepatitis B vaccines, which have been around for decades, prevent liver cancer, while HPV vaccines, launched in 2006 to protect cervical cancer.

Dr. Susan Domchek, Director of the Basser Center at Penn Medicine in Philadelphia, is seeking 28 healthy patients with BRCA mutations for a vaccination test. These mutations enhance the risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer. The goal is to eliminate aberrant cells at an early stage, before they create problems. She compares it to tending a garden or erasing a blackboard on a regular basis.

Those who have precancerous lung nodules and other genetic diseases that increases the likelihood of contracting cancer are being protected against it with vaccines being developed by others.

“Vaccines are probably the next big thing” in the fight to minimize cancer fatalities, according to Dr. Steve Lipkin, a Medical Geneticist at New York’s Weill Cornell Medicine. “We’re dedicating our lives to that.”

A lifetime chance of acquiring cancer ranges from 60% to 80% for those who have Lynch syndrome, a genetic disorder. According to Dr. Eduardo Vilar-Sanchez of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, enlisting people for cancer vaccine trials has been extremely simple. “Patients are jumping on this in a surprising and positive way,” he said.

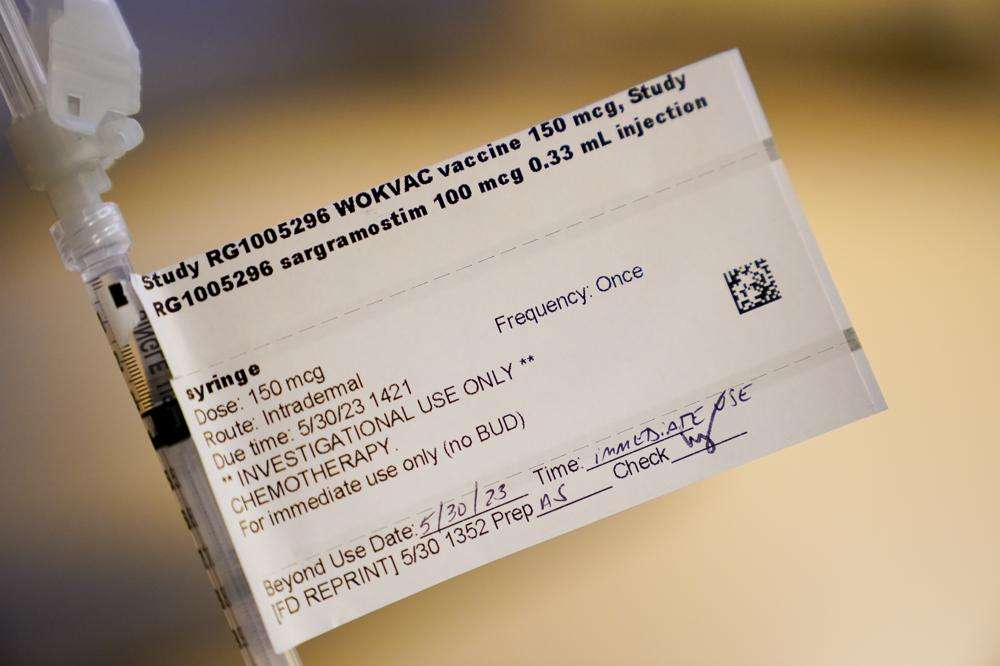

A significant trial on the tailored mRNA vaccine for melanoma patients will commence this year, thanks to a collaboration between the pharmaceutical companies Moderna and Merck. Based on the various mutations found in the cancer tissue of each patient, the vaccinations are individually tailored for them.

A vaccination that has been tailored in this way, can train the immune system to look for and kill cancer cells that have a mutation fingerprint. However, such vaccines would be very expensive.