In a nation wrestling with judicial retirement benefits that are increasingly out of step with its economic reality, legal scholar Prof. Stephen Kwaku Asare has raised pointed questions about the sustainability and fairness of elite compensation—particularly for senior members of the judiciary.

Against a backdrop of national debt restructuring, IMF conditionalities, unpaid contractors, chronic underfunding of education and healthcare, and seasonal flooding, Prof. Asare asks: Can Ghana continue to afford such largesse at the top?

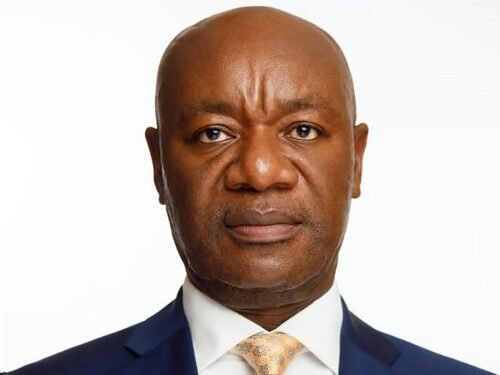

Prof. Asare singled out the case of a Justice of the Court of Appeal as a prime example of what he described as an overly generous and deeply burdensome system.

Currently, justices retiring after about 25 years of service on the Superior Court of Judicature walk away with retirement packages that most citizens would find unimaginable.

“Let’s do the math. The current monthly salary for a Justice of the Court of Appeal is ₵62,202.53. Upon retirement, the justice continues to receive this amount every month for life—and that amount is automatically adjusted upward any time the salary of sitting justices is increased. In effect, the pension is indexed not to inflation, but to salary growth, which is even more generous.”

Prof. Stephen Kwaku Asare

Yet, the monthly lifetime pension tells only half the story. In addition to that, retiring justices are awarded a lump sum gratuity—commonly known as ex gratia—calculated at four months’ salary for each year of service.

For a judge stepping down after 25 years on the bench, the figures become staggering.

“4 x 25 x ₵62,202.53 = ₵6,220,253. Yes, over six million cedis—paid as a lump sum upon retirement. This is in addition to a lifetime pension that starts at over ₵746,000 annually, with built-in upward adjustments.”

Prof. Stephen Kwaku Asare

Public Burden, Private Judicial Gains

Furthermore, Prof. Asare acknowledged that for the individual judge, such a package is undeniably rewarding. However, for the national budget—and taxpayers footing the bill—it is a different story.

He pointed out that if just ten justices retire in a given year under these terms, the state could spend over ₵62 million in gratuities and nearly ₵8 million annually in pensions—costs that will only grow over time. “And this does not include healthcare, security, drivers, housing, or other post-retirement benefits that may attach to the office.”

While in theory, generous judicial compensation is intended to safeguard judicial independence by shielding judges from corruption and political pressure, Prof. Asare believes the pendulum has swung too far.

He acknowledged that, in theory, providing generous compensation to judges can be justified as a way to shield them from corruption, ensure financial stability, and uphold their independence in defending the rule of law.

However, he emphasized that such ideals must be examined in light of real-world conditions. In Ghana’s present economic climate, the disparity between the privileges enjoyed by the elite and the daily challenges faced by the average citizen is especially striking.

“The reality is: National service personnel earn less than ₵1,000 per month; Medical doctors and other health professionals are underpaid and under-resourced; Many public workers face arrears and delayed salary adjustments; Citizens were forced to accept ‘haircuts’ on government bonds and pensions; Hospitals and schools routinely lack essential supplies due to budget shortfalls; Accra floods when it rains.”

Prof. Stephen Kwaku Asare

Given the current circumstances, Prof. Asare raised a pointed concern about whether it is justifiable to allocate millions of cedis to a single retiree when essential public services across the country continue to suffer from chronic underfunding.

Calls For Urgent Pay Reform

Moreover, from Prof. Stephen Asare’s perspective, the existing structure of judicial retirement benefits falls short on all three key pillars of responsible public policy: fairness, effectiveness, and sustainability.

According to him, it disproportionately favors a privileged minority, serves primarily to enrich a small elite, and can only be maintained if the broader population continues to endure long-term economic hardship.

He argued that reforming how judges are paid does not have to mean weakening judicial independence. Rather, it requires a careful rebalancing of what he called “judicial privilege” and public interest.

“Reforming judicial pay should not mean undermining judicial independence. But judicial privilege must not become judicial exceptionalism. If we are all in this republic together, then burdens and benefits alike must be shared more equitably.”

Prof. Stephen Kwaku Asare

Prof. Asare did not spare the bodies responsible for crafting these lucrative arrangements.

“The ‘Professor this, Professor that’ Emoluments Committee appears more committed to academic abstraction than fiscal responsibility—crafting golden parachutes in an economy begging for lifeboats.”

Prof. Stephen Kwaku Asare

He concluded with a pointed reflection on the meaning of justice and the widening gap between privilege and sacrifice in Ghana’s economy.

The question, at its core, is whether it is morally defensible to grant retiring justices lavish financial packages while the average citizen is continually asked to endure austerity measures, make sacrifices, and accept reduced benefits.

As public debate intensifies around how national resources are allocated and what kind of governance the country should aspire to, voices like Prof. Asare’s are not promoting cynicism—they are pushing for immediate, principled, and transparent reform, especially in the area of judicial retirement compensation.

READ ALSO: Fitch Forecast Fuels Hopes for Renewed Equity Appetite in Ghana- Analyst Weighs In