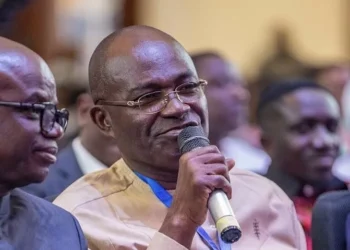

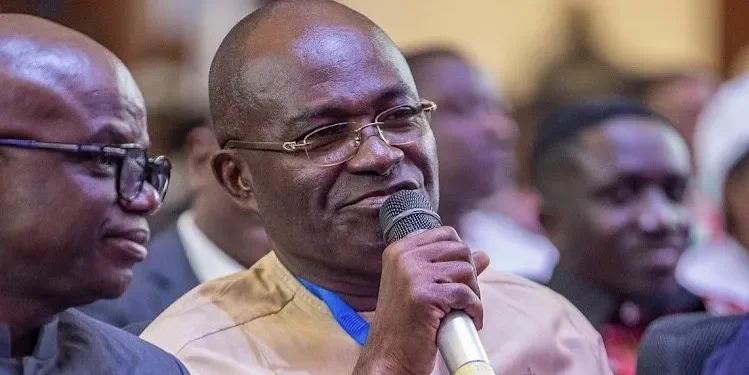

Ghana’s banking and deposit insurance system is under fresh scrutiny following a sharp critique by Bright Simons, Vice President of IMANI Africa, who is urging a more robust and transparent national learning framework for public policy.

According to Simons, the country’s ability to analyze, refine, and apply policy decisions remains worryingly underdeveloped, especially in sectors like banking and finance.

Simons emphasized the need for consistent “national learning” within African public policy, noting that tracking policy choices is important but not sufficient.

What is even more essential, he stressed, is the ability to evaluate whether policymakers are learning from past mistakes and aligning decisions with the nation’s long-term development goals.

“I describe as ‘katanomics’ the inability to map policy choices & decisions to desired political & public welfare outcomes due to broken national policy accountability.

“One great example of a Ghanaian context, in this light, is the 2017–19 Financial Cleanup. What has Ghana learnt and how are the resultant lessons reflected in policies? If you live in Ghana and are relatively educated but have no clue, then my point is made.”

Bright Simons

He pointed to the introduction of a deposit insurance scheme in 2019 as a key policy intervention intended to cushion the impact of future bank failures and restore confidence in Ghana’s financial system.

Under this initiative, individual depositors are guaranteed a maximum payout of 6,250 Ghanaian cedis if their bank goes under.

While this represents a step toward safeguarding consumer savings, the protection it offers is relatively limited—especially when compared to global standards.

For instance, in the United States, the equivalent deposit insurance scheme ensures coverage of up to $250,000 per account holder in the event of a bank collapse.

This stark contrast underscores the inadequacy of Ghana’s safety net and raises concerns about whether the policy, in its current form, can effectively protect the average depositor or prevent widespread panic during future financial crises.

Policy Accountability In Ghana’s Banking Urged

Furthermore, Bright Simons drew attention to the gap between policy intent and public understanding.

Simons argued that although banking in Ghana is considered more elite than in the U.S., the limited coverage still falls short.

The average bank balance in Ghana is around 8,000 GHS, he noted, while in the U.S. it’s approximately $62,000, with a median closer to $8,000.

This means the U.S. maximum payout is roughly four times the average balance, whereas Ghana’s payout does not even cover the average.

“The US scheme will extend insurance coverage to multiple categories of accounts held with the collapsed bank, such as joint A/Cs, trusts, & pension accounts. Meaning a saver can get far more than the $250k max.”

Bright Simons

Despite this disparity in coverage, Ghanaian banks pay higher premiums for deposit insurance—between 30 and 150 basis points—while U.S. banks have historically paid between 2 and 42 basis points.

Simons attributed this difference in part to the maturity of the U.S. system and its use of refined risk models developed over decades.

“Every time there is a collapse or broad crisis, the lessons are fed back into the model. The key question is always thus: how good was the model and resultant premium rate in predicting distress at a bank?”

Bright Simons

Simons lamented the lack of transparency in the stress-testing of Ghana’s deposit insurance scheme.

He expressed concern that without robust collaboration among banks, regulators, policymakers, and research institutions, the system would not evolve to meet its intended purpose.

He cautioned that without accurate modeling and transparency, deposit insurance in Ghana might remain a nominal safety net—one that offers little practical protection or reassurance in a crisis.

The system’s effectiveness, he suggested, is already diminished by public ignorance.

Simons was unequivocal in his conclusion: unless Ghana cultivates a culture of transparency and accountability in public policy, particularly in critical sectors like finance, the country will continue to repeat its mistakes.

“The first objective of deposit insurance is to minimize the panic that leads to bank runs whilst guarding against moral hazard. To repeat: national learning requires transparency and accountability.”

Bright Simons

His remarks serve as a wake-up call for policymakers and the general public alike.

As Ghana continues to fortify its financial systems, the true measure of progress will lie not in the number of policies announced, but in how well those policies are understood, implemented, and improved upon through honest national introspection.

READ ALSO: Russia Schedules Next Round Of Ukraine Talks For June 2