Ghana’s long-standing battle with electoral violence has once again sparked serious concern, as Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare, legal expert and Democracy and Development Fellow at CDD-Ghana, has highlighted the dangerous pattern of normalization surrounding political bloodshed.

According to him, the nation has fallen into a repetitive cycle where violence erupts during elections, receives public condemnation, and then fades into political silence—without any tangible action to bring perpetrators to justice or prevent future chaos.

He pointed out that every election season in Ghana seems to follow the same grim sequence: violence erupts, authorities and political leaders issue public statements denouncing the incidents, and life moves on.

However, Prof. Asare warned that this response is far from being a genuine commitment to peace.

“Condemning and moving on isn’t peace. It’s permission. Permission for parties to regroup and reload for the next round of violence. The cycle of violence → condemnation → inaction must end. Condemnation is meaningless unless it’s backed by prosecution, structural reforms & preventive enforcement.”

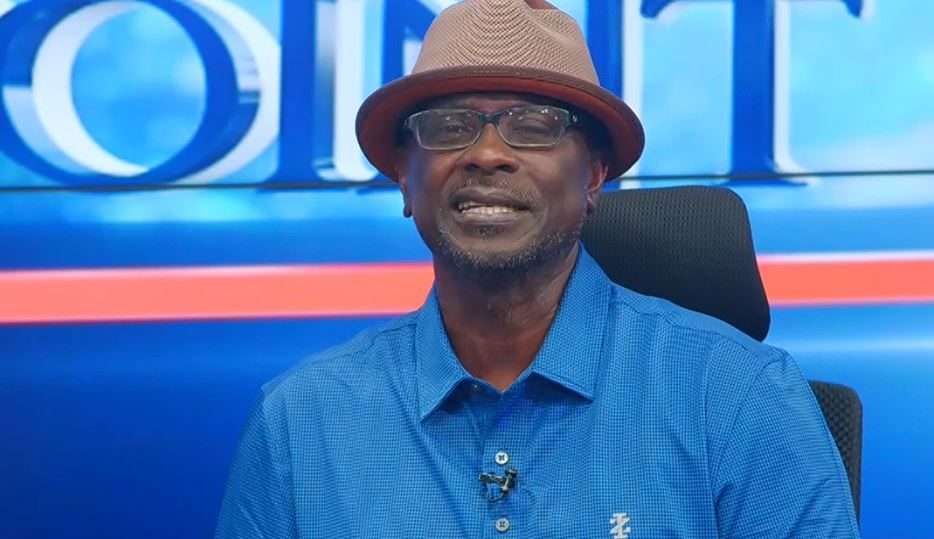

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

Over the years, Ghana has witnessed several hotspots where electoral violence repeatedly rears its head. Prof. Asare drew attention to some of the most notorious incidents in the country’s electoral history.

He cited the 2000 Bawku clashes, which claimed over 30 lives, as ethnic and political tensions between the NPP and NDC spiraled into deadly violence. The 2004 general elections saw journalists targeted in Tamale and the Volta Region, with over 27 violent incidents reported during voting.

The trend continued in 2009 during the Chereponi by-election, where NDC and NPP supporters clashed violently, as well as in 2010 during the Atiwa by-election, remembered for attacks following the NPP’s victory.

In 2015, violence erupted in Talensi, where political vigilante groups armed with guns and machetes turned polling areas into battlegrounds.

More recently, the 2019 Ayawaso West Wuogon incident saw national security operatives fire live ammunition, injuring 18 people and forcing the NDC to withdraw from the polls.

The 2020 general election followed a similar trajectory, with five deaths and over 60 violent episodes recorded, particularly in hotspots like Techiman South and Odododiodio.

In the 2024 general election, chaos erupted during collation in nine constituencies. In 2025, violence returned during the Ablekuma North rerun elections, where allegations of vote-buying, physical intimidation, and attacks on journalists and women marred the process.

Political Greed Feeds Electoral Violence

According to Prof. Stephen Asare, the primary driver of electoral violence in Ghana is the excessive value placed on political power.

Once political dominance is secured, parties exploit it as a tool to govern without checks. Ironically, many of those who suffer under abuses of power are often recruited as foot soldiers to fight for it during elections.

This vicious cycle, Prof. Asare noted, is perpetuated by deliberate legal loopholes that empower vigilante groups to act with impunity. In Ghana’s current system, the absence of punishment effectively encourages violence, serving the interests of powerful political actors.

Prof. Asare issued a stark warning: “ENOUGH IS ENOUGH. LET’S CLEAN HOUSE.” His recommendations for breaking the cycle of electoral violence are comprehensive and practical.

First, he proposed restricting access to polling stations to voters and accredited agents only, eliminating the interference of political operatives and so-called big men.

To further secure polling environments, he recommended banning all weapons within a 500-meter radius of voting centers and prohibiting the loitering or congregation of non-voters near these critical locations.

“Blacklist election offenders—permanent voting ban & no public office. Prosecute vigilante groups. Prosecute election crimes immediately—with prosecutors independent of political control.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare

Transparency during the collation process is also essential, according to Prof. Asare. He suggested live-streaming vote collation as a form of public oversight, noting that “sunlight is the best disinfectant.”

Moreover, he called for empowering Ghana’s police forces to secure elections—preventing political thugs from assuming control over electoral security.

Prof. Asare concluded with a somber reminder: unless Ghana takes deliberate steps to dismantle the structures that enable electoral violence, its democracy will continue to be threatened, with places like Akwatia potentially turning into future battlefields.

His message is clear—without structural reforms, prosecutorial action, and preventive security measures, Ghana’s electoral future remains precarious.

Meanwhile, some may argue that Ghana’s recurring electoral violence reflects deeper societal tensions that legal reforms alone cannot resolve.

Without addressing underlying political polarization and economic disparities, structural changes risk treating symptoms rather than the root causes of unrest.

READ ALSO: Importers Back Mahama’s Push to Regulate Port Fees, Predict Market Relief