The charge that “religion and education are killing us” is provocative, but it captures a real frustration: many Ghanaians feel that social progress is being held back by uncritical deference, toward religious authorities, traditional hierarchies, and exam-driven schooling.

The problem is not Ghanaian identity or faith itself; rather, it is how religious practice and formal education often operate in ways that discourage questioning, independent reasoning, and intellectual risk-taking.

If Ghana is to unlock human potential and meet 21st‑century challenges, it must reform both the cultural and institutional incentives that undermine critical thinking.

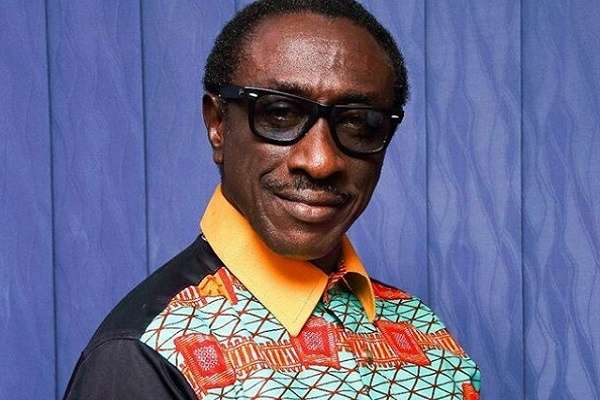

Ghanaian comedian and social commentator Kwaku Sintim-Misa, popularly known as KSM, has argued that Ghana’s biggest challenge is the absence of critical thinking.

KSM dismissed the notion that white people are inherently more intelligent than black people, stressing that Ghana’s underdevelopment stems not from a lack of intelligence but from a failure to thick critically about societal issues.

“When people say white people are superior to blacks in terms of intelligence, I don’t agree with that. However, our problem is not that blacks are inferior, it is that we, especially Ghanaians, lack critical thinking.”

KSM

He identified religion and religion and education as the two major factors suppressing critical thinking in Ghana.

According to him, both institutions could be positive forces if people apply reasoning and relevance of their practices.

“Religion can be positive if you think critically and make it applcable in your life. Education is only important when we interpret it to make it relevant to our circumstances.”

KSM

Religion in Ghana is pervasive and diverse, and for many people provides moral guidance, community networks, and social support. Yet certain dynamics within religious life unintentionally discourages skepticism and independent judgment.

Charismatic leadership, prosperity-focused messages, and congregational cultures that valorize doctrinal certainty over debate create environments where dissent or inquiry is stigmatized.

When religious leaders are also powerful social or political brokers, people who question them face social or economic costs. In public debates, on health, science, or governance, faith-based claims sometimes outrun evidence.

That gap fosters conspiracy thinking or mistrust of expert opinion if questions are framed as breaches of loyalty rather than opportunities for constructive dialogue.

Ghana’s formal education system has many strengths, high enrollment rates, committed teachers, and a national desire for credentials. However, the system still bears hallmarks of an exam-focused, colonial-inherited model that prizes memorization and standardized answers.

Teaching to the test, large class sizes, limited resources, and assessments that reward recall over analysis make it difficult for schools to model and reinforce critical thinking.

Consequences: Governance, Public Health, and Innovation

The practical costs of weak critical-thinking skills are tangible. Political discourse become a personality-driven and susceptible to misinformation when citizens do not scrutinize claims or demand evidence.

During health emergencies or debates about technology and public policy, the inability to evaluate sources and weigh trade-offs undermines effective responses.

Economically, a workforce that lacks higher-order reasoning and creative problem-solving will struggle to compete in knowledge-intensive sectors.

These are not speculative concerns: policy analysts and international organisations have repeatedly linked improved learning outcomes, including critical thinking, to better development outcomes.

The claim that “religion and education are killing us” overstates and sensationalizes a complex reality, but it captures an important warning: institutions and cultures unintentionally reward conformity and deference at the expense of independent thought.

For Ghana, the remedy is not to abandon faith or schooling but to reform how both operate, promoting curricula and religious practices that value questioning, evidence, and humility.

By investing in teachers, assessments, media literacy, and constructive engagement with faith communities, Ghana cultivates a citizenry capable of critical judgment, resilient in the face of misinformation, and ready to drive inclusive development.

The challenge is urgent but solvable, and the payoff for democratic life, public health, and economic innovation would be immense.

READ ALSO: Kwabena Agyepong Touted as NPP’s Best Bet for 2028 Victory