Dr. Ohene Aku Kwapong, Democracy and Development Fellow at the Ghana Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana), has issued one of his most forceful analyses yet on Ghana’s worsening educational outcomes, arguing that the system is not merely underperforming but collapsing under deep structural failures that begin as early as Basic 1.

In a detailed reflection, he described the current crisis as the predictable culmination of years of neglected fundamentals, overstretched infrastructure, and a teacher training pipeline that admits academically weak candidates into the profession responsible for shaping the nation’s future.

According to Dr. Kwapong, public debate often focuses on high-performing schools such as Prempeh College or Presbyterian Boys’ Senior High School, but the true origins of the crisis lie far earlier.

“Every year, hundreds of thousands of children complete junior high school with staggering deficits in literacy and numeracy. They cannot read with fluency. They cannot write with clarity.

“They cannot perform arithmetic with confidence. By the time these students enter senior high school, the damage is already done. Senior high schools are not receiving learners. They are receiving remediation cases.”

Dr Ohene Aku Kwapong, CDD Ghana Fellow

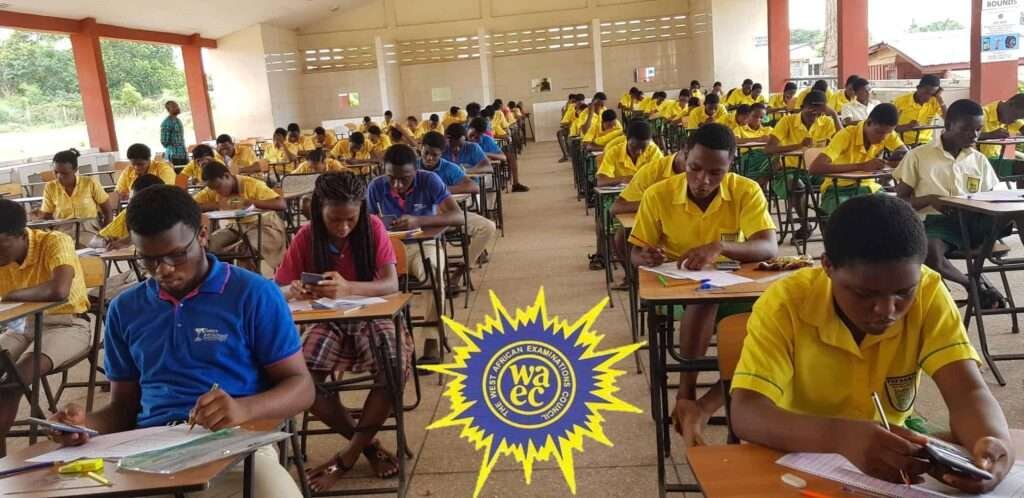

For Dr. Kwapong, the poor results emerging from the West African Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE) are simply the final exposure of weaknesses embedded in the system years earlier. He noted that no senior high school system anywhere in the world can build higher-order reasoning on a foundation that never existed.

Double Track System Catastrophic Execution

Turning to the double track system introduced in 2018, Dr. Kwapong described it as “clever in theory, catastrophic in execution.” The idea, he explained, was straightforward: increase efficiency by running schools year-round and reducing idle classroom time.

“On paper, it is an efficiency solution,” he acknowledged. But while the buildings were indeed used twice as hard, the operational system was not strengthened accordingly.

“The state increased enrollment without increasing the operational backbone: not enough teachers, not enough teaching assistants, not enough materials, not enough labs, not enough supervision”.

Dr Ohene Aku Kwapong, CDD Ghana Fellow

What followed, he said, was predictable—overcrowding and a marked decline in quality. Prempeh College now hosts nearly 4,000 students, while PRESEC-Legon has about 3,000.

The most recent WASSCE results, in his view, make the decline unmistakably clear. The numbers tell a stark story: 131,097 failed English Language; 220,008 failed Core Mathematics; 161,606 failed Integrated Science; and 196,727 failed Social Studies. Yet Dr. Kwapong noted that these failures represent only those who survived long enough to sit for the exams.

When this cohort began Primary 1 twelve years earlier, he estimated that roughly four million children were in the system. Only a fraction made it to SHS completion, and nearly half of those who did failed the most basic core subjects. “This is not a performance problem,” he concluded. “It is a structural implosion.”

Teaching Deficits

A significant part of the collapse, Dr. Kwapong argued, is rooted in the caliber of teachers the system attracts and trains. He described a longstanding pattern in which students unable to gain admission into competitive universities enter teacher training colleges by default.

“Teaching becomes the fallback option,” he wrote. As a result, many teachers enter classrooms carrying the same literacy and numeracy weaknesses they are expected to remedy in their students.

By contrast, countries such as Estonia, South Korea, Singapore, and Malaysia—nations that have “diverged from Ghana”—demand rigorous subject-matter mastery before pedagogical training.

Ghana, he noted, attempts the reverse: training pedagogy first and hoping subject competence will follow. “It never does,” he stressed, adding that “a system cannot produce what its teachers do not possess.”

Quoting EduWatch Executive Director Kofi Asare, Dr. Kwapong highlighted seven areas in which Ghanaian candidates performed poorly in the 2025 WASSCE Core Mathematics examination.

These include representing mathematical information in diagrams, solving global math-related problems, constructing cumulative frequency tables, interpreting cumulative frequency data, solving simple interest applications, translating word problems into mathematical expressions, and making deductions from real-life problems.

To him, these are not advanced topics but foundational tools of mathematical reasoning. “Any competent mathematics teacher anywhere in the world should be able to teach these in their sleep,” he argued. The fact that students failed them “at scale,” he said, is evidence that “far too many of their teachers cannot do these tasks either.”

Dr. Kwapong also linked Ghana’s stagnating productivity and slow economic transformation to the failing education system. While senior secondary completion rates have risen, he noted that quality has declined sharply.

Countries that have successfully transformed their economies, he argued, did so by building a well-educated workforce capable of absorbing new technologies, adapting to emerging demands, and solving problems with minimal supervision.

“Unfortunately, while our school completion rates are rising, the quality is falling. That is why productivity stagnates. That is why innovation falters.”

Dr Ohene Aku Kwapong, CDD Ghana Fellow

Struturaal Reforms

To arrest the decline, Dr. Kwapong proposed four major structural reforms, which he described not as suggestions but as “systemic repairs.” First, he called for decentralizing school management to districts and municipalities, arguing that Accra cannot effectively manage 16,000 schools from the center. Local accountability, he insisted, is “non-negotiable.”

Second, he urged the government to downsize the Ghana Education Service (GES) by about 70 percent and convert it into a standards and outcomes agency focused on curriculum, certification, data, and national benchmarks. He described the current structure as “managerial obesity.”

Third, Dr. Kwapong argued that teachers must earn full degrees in substantive subjects before receiving pedagogical training or certification. Mathematics teachers must be trained mathematicians; English teachers must be fluent readers and writers; science teachers must be scientifically literate. “No exceptions. No shortcuts,” he emphasized.

And finally, he called for savings from GES downsizing to be redirected into raising teacher salaries at the district level, arguing that “a professionalized corps of teachers cannot be paid like casual laborers.” He further suggested that proceeds recovered from corruption should be allocated to strengthen incentives for recruiting higher-quality teachers.

Dr. Kwapong ended with a clear warning: Ghana cannot hope to grow its economy on the back of weak primary foundations, overcrowded secondary schools, and low-quality teaching.

The connection between education and economic growth, he argued, “is not abstract. It is mechanistic.” For true transformation, Dr Kwapong urged the country to build the cognitive capacity of its children. “That requires redesigning the system, not patching it,” he concluded, stressing that “it always comes down to political will and seriousness of purpose.”

READ ALSO: Non-Interest Banking Era Nears Reality as BoG, SEC and NIC Unveil Joint Regulatory Push