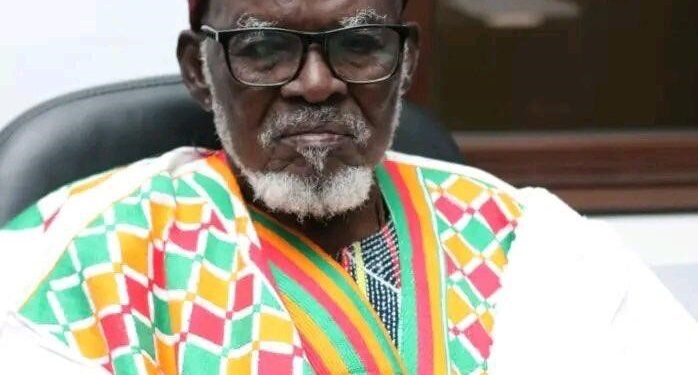

Vice President of policy think tank IMANI Africa, Bright Simons, has issued a strong warning over the Bank of Ghana’s proposed regulatory framework for Non-Interest Banking, describing it as confusing, legally risky, and potentially doomed to fail if not corrected.

His concerns were outlined in a detailed article responding to the central bank’s exposure draft, which seeks to regulate what it now calls Non-Interest Banking instead of Islamic Banking.

According to Mr. Simons, the attempt to rebrand Islamic Banking under a neutral label may have been driven by a desire to avoid religious controversy. However, he argues that the move has instead created deep contradictions that could undermine the credibility and functionality of the entire sector.

Rebranding Islamic Banking Creates Identity Crisis

At the heart of Bright Simons’ criticism is the Bank of Ghana’s decision to replace the term Islamic Banking with Non-Interest Banking. He contends that this change fails to reflect the true nature of the financial model being introduced. While the guidelines prohibit religious language and symbols, they still require compliance with standards developed by the Accounting and Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions.

Mr. Simons argues that this contradiction sends mixed signals to banks, customers, regulators, and the courts. In his view, calling the framework Non-Interest Banking while anchoring it firmly in Islamic financial principles creates an identity crisis that could confuse stakeholders and weaken trust in the system.

He notes that non-interest financial models around the world are overwhelmingly rooted in Islamic jurisprudence and ethics. Attempting to separate the practice from its foundation, he warns, risks misrepresenting the product and misleading the public.

Absence of Dedicated Islamic Banking Law Raises Legal Risks

Another major concern raised by the IMANI Africa vice president is the lack of a dedicated Islamic Banking law in Ghana. He points out that without clear legislation, the courts may struggle to interpret and enforce contracts arising from non-interest banking products.

According to Mr. Simons, many Islamic finance arrangements rely on concepts such as profit sharing, partnerships, and asset backed transactions. These ideas are derived from Islamic jurisprudence rather than Ghana’s statutory or common law framework. He warns that disputes involving such contracts could create legal uncertainty and prolonged litigation, undermining confidence in the sector.

He cautions that regulators and judges may find it difficult to resolve disputes fairly without explicit legal guidance, particularly in a secular legal system like Ghana’s.

Window Model Could Encourage Regulatory Abuse

Mr. Simons also criticises the window model proposed in the draft guidelines. This model allows conventional banks to offer non-interest banking products alongside their traditional interest-based services.

He warns that this approach could be exploited by banks seeking to benefit from regulatory or tax incentives associated with non-interest banking without fully adhering to its core principles. In his assessment, such abuse could distort competition and weaken the ethical foundation of non-interest banking, which is built on risk sharing rather than guaranteed returns.

According to him, without strict safeguards, the window model could become a loophole rather than a pathway to financial inclusion.

Unresolved Issues on Taxation and Financial Stability

Beyond legal and identity concerns, Bright Simons raises serious questions about the economic viability of the proposed framework. He highlights unresolved issues around taxation, deposit protection, liquidity management, and capital adequacy.

He argues that the exposure draft does not adequately explain how non-interest banks will operate on a level playing field within Ghana’s existing financial and tax systems. Without clarity, such banks could face unfair disadvantages or unintended costs that make them less competitive than conventional institutions.

Mr. Simons also questions provisions that prevent non-interest banks from benefiting from late payment penalties. He warns that this could weaken repayment discipline and expose banks to higher default risks, threatening their financial sustainability.

A Framework That Looks Good but May Fail in Practice

In his conclusion, the IMANI Africa vice president delivers a stark warning. He says the Bank of Ghana risks creating a non-interest banking sector that appears impressive on paper but struggles to function in reality.

According to him, genuine success requires honesty about the nature of Islamic Banking and the introduction of clear supporting laws. These should cover taxation, liquidity support instruments such as Islamic bonds, dispute resolution mechanisms, and consumer protection.

Without these reforms, Mr. Simons cautions that Ghana’s non-interest banking initiative could become ineffective and unattractive to both banks and customers. He urges the Bank of Ghana to revisit the framework and adopt a more transparent and legally sound approach that aligns policy intent with practical realities.

READ ALSO: NRSA Demands Dedicated Motor Lanes to Curb ‘Meandering’ After Okada Legalization