Ghana’s newly established GoldBod has been widely hailed as a transformative reform aimed at improving transparency, boosting gold exports and strengthening foreign exchange inflows.

However, tax consultant Francis Timore Boi has urged caution, warning that it is premature to celebrate the initiative without addressing lingering questions about illegal mining and the destination of unlawfully produced gold.

According to Mr. Boi, any assessment of GoldBod’s success must confront a fundamental gap in Ghana’s gold value chain: the continued flow of gold from illegal mining operations and the absence of clarity on who ultimately buys it.

“Once we praise the GoldBod to be one of the most impactful extractive sector reforms in Ghana, there is a bigger, very thick issue.

“The illegal miners and the gold they produce, who buys them? These are the questions that we have not been able to answer.”

Francis Timore Boi, Tax Consultant

Illegal Mining Still Thriving

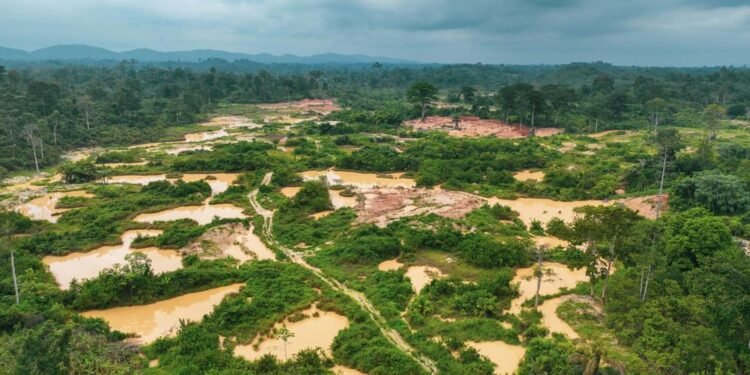

Despite years of enforcement campaigns against illegal mining, commonly known as galamsey, Mr. Boi said the practice remains widespread across the country.

He argued that this reality weakens claims of comprehensive reform in the gold sector, as long as illegal production continues largely unchecked.

“Every day we see the illegal miners producing, excavating here and there, and you and I are paying for it,” he stated, pointing to the visible environmental degradation caused by unregulated mining.

According to him, the persistence of galamsey suggests that reforms focused solely on formal structures risk overlooking a significant portion of gold production that operates outside official systems.

Mr. Boi linked illegal mining directly to rising utility costs, arguing that environmental destruction ultimately translates into higher living expenses for ordinary Ghanaians. He cited water pollution as a clear example of how galamsey affects households far removed from mining sites.

Polluted rivers and water bodies, he explained, have forced water treatment companies to invest more heavily in purification processes.

“I wasn’t surprised when Ghana Water said they were going to increase the tariff.

“They can’t process their water the way it used to be. They have to expend more, and so we are all paying for it.”

Francis Timore Boi, Tax Consultant

In his view, these hidden costs make illegal mining not just an environmental issue, but an economic burden shared by the entire population.

Where Does the Illegal Gold Go?

Central to Mr. Boi’s critique is the lack of traceability in Ghana’s gold sector. He questioned whether gold produced through illegal mining is somehow being absorbed into official channels, including the GoldBod framework.

“The question is, where is the gold? Is it coming to the GoldBod?” he asked, underscoring the opacity surrounding the flow of illegally mined gold.

He further pointed to the supply chains that support illegal mining, including the importation of excavators and chemicals used in gold processing.

According to him, these inputs do not appear by chance. “We don’t know who the importers of excavators are. The chemicals they use to process gold, we don’t fetch it like water,” he said.

These unanswered questions, he argued, indicate that illegal mining is sustained by networks that require closer scrutiny.

Mr. Boi described the situation as a “thicker issue” that goes beyond surface-level reforms. He suggested that Ghana must confront uncomfortable questions about enforcement, accountability and institutional coordination if it is serious about transforming the gold sector.

“There is a thicker issue that, maybe as a country, we will have to start asking questions. Where is the produce going?”

Francis Timore Boi, Tax Consultant

Without resolving these structural weaknesses, he warned, reforms risk addressing symptoms rather than root causes.

Measuring GoldBod’s True Impact

While acknowledging the potential benefits of GoldBod, including increased dollar inflows and support for currency stability, Mr. Boi insisted that such gains must be evaluated in context. He argued that only by accounting for illegal production can Ghana accurately measure the reform’s impact.

“If we are able to answer that question, then we can either celebrate the GoldBod as doing a fantastic job by helping us get more dollars to stabilise the cedi.”

Francis Timore Boi, Tax Consultant

He said, referencing the praise often directed at the Bank of Ghana and the Ministry of Finance for recent economic improvements. Until then, he cautioned against drawing overly optimistic conclusions.

Mr. Boi ended with a stark warning that misreading the state of the gold sector could have long-term consequences. Celebrating reforms without confronting illegal mining, he suggested, risks creating a false sense of progress.

“Until we are able to answer where the illegal mining produce is going, maybe we’ll be shooting ourselves in the foot.

“We may think we have bitten our tongue and gotten some nice meat that we are chewing, but it will be the contrary.”

Francis Timore Boi, Tax Consultant

For him, the message is clear: GoldBod may represent a step forward, but its success will ultimately depend on whether Ghana can bring the shadow economy of illegal gold into the light.

READ ALSO: EOCO Recovers GHS337m, Smashes 2025 Target