Author: Dr. John Osae-Kwapong, Democracy and Development Fellow, CDD-Ghana, and Project Director, the Democracy Project

Barely a month prior, the military successfully seized power in Guinea-Bissau as voters waited for the declaration of election results, which both the incumbent and main opposition candidate claimed victory. All this comes at a time when, within the last five years, there have been successful military takeovers in Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, and Guinea.

On December 7, the world woke up to news of a military coup in Benin. Videos of soldiers announcing the takeover on state-owned media brought back memories of a sub-region’s post-independence trajectory, which for a long time was bedeviled with military coups.

For pro-Democracy forces, especially in West-Africa, this was another warning signal of the dangers facing democratic governance in the region and the urgent need to turn the tide around. Thankfully, within 24hours, the Benin government announced that the coup had failed with further reports of military support from Nigeria.

While relieved that the attempted coup failed, it reminded me of the warning former president of Ghana Nana Akufo-Addo, issued to his West-African colleagues in 2023 that “democracy is West-Africa is in danger.”

And the fact that the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), following the attempted coup, announced the deployment of its standby force to protect Benin was the clearest signal that the regional bloc recognizes the grave danger facing the sub-region.

Why Is Democracy Vulnerable in The Sub-Region?

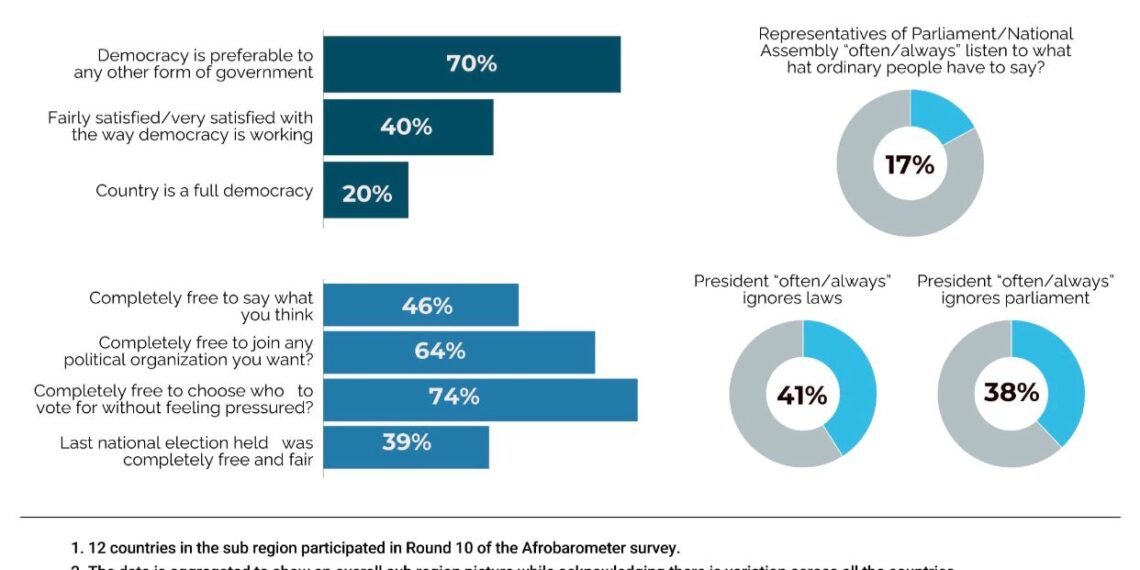

In examining data from the Afrobarometer survey of the 12 countries (Benin, Cabo Verde, Côte d´Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Nigeria, Senegal, and Sierra Leone) in the region that participated in Round 10 (2024/2025), here are some of the points of vulnerability.

The data is aggregated to show a regional picture but keep in mind that there are variations across all the countries mentioned here. First, there is a wide gap between support for democracy and satisfaction with the way democracy is working.

In a region where seven out of ten citizens (70%) say “democracy is preferable to any other form of government,” it is worrying to see that only 40% say they are “fairly satisfied/very satisfied” with the way democracy is working.

Second, citizens’ assessment of democracy is not encouraging, with 63% describing democracy as having “minor/major” problems. Only 19% describe their countries as a “full democracy.” This is surprising because citizens do believe they enjoy certain basic democratic freedoms.

For example, 74% say they are completely free “choose who to vote for without feeling pressure.” I must note though that only 45% say they are completely free to “say what they think.” Perhaps citizens require a full democratic experience in addition to these basic freedoms.

Third, is the issue of election. When one thinks of how central electoral competition is to democracy, especially as the key tool for deciding how power is won or lost, then it is important that citizens have high regard for the integrity of the electoral system. However, in this survey, only 40% rated elections as “completely free and fair.” In addition, only 18% express “a lot” of trust in election management bodies.

Fourth, 56% of citizens agree that “it is legitimate for the armed forces to take control of government when elected leaders abuse power for their own ends.” While it may never come to that, it is still very concerning that almost six out of ten citizens in the region are willing to give conditional legitimacy to military intervention.

Fifth, and this is from Afrobarometer Round 9 (2021/2023), the level of democratic optimism was not very reassuring because only 38% answered “somewhat/more democratic” when asked “do you think that in five years’ time this country will be more democratic than it is now, less democratic, or about the same?”

For context, and why this is problematic, in the survey 68% described democracies in their countries as having problems. This illustrates a lack of faith in improved democratic outcomes at a time when citizens recognized that democracy faced problems.

Food for Thought

While some of the above identified vulnerabilities are not a justification for military interventions, they help expose the fault lines of the current state of democracy in West-Africa. In addition, they lend themselves to exploitation by those not committed to the democratic peace and stability of countries in the sub-region.

I am encouraged by the actions of ECOWAS in response to what happened in Benin. Yes, each country has responsibility for safeguarding its own democracy, but the potential ripple effects of democracies falling apart in the region make it imperative to design a collective response.

It is a trying time indeed but the need for ECOWAS’ leadership has never been this critical since the transitions to democracy that swept not only West Africa but Sub-Saharan Africa in the 1990s.

READ ALSO: Mahama Inspects Takoradi–Agona–Nkwanta Road, Directs $78m Payment to Speed Up Completion