The decision by the New Patriotic Party to initiate internal processes to expel Professor Kwabena Frimpong Boateng has once again drawn national attention to the long-standing practice of sacking party members in Ghana.

While such actions have become familiar across the political divide, a fellow of the Centre for Democratic Development, Ghana, and legal scholar, Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare, argued that the ritual of expulsions has little constitutional basis and weakens democratic culture rather than strengthening party discipline.

“It is not the first time a political party has taken steps to expel a prominent member, and it will certainly not be the last. Such expulsions are familiar features of our political landscape.

“They are also bipartisan. Over the years, both major parties have expelled, suspended, or threatened to expel members for indiscipline, dissent, or public criticism.”

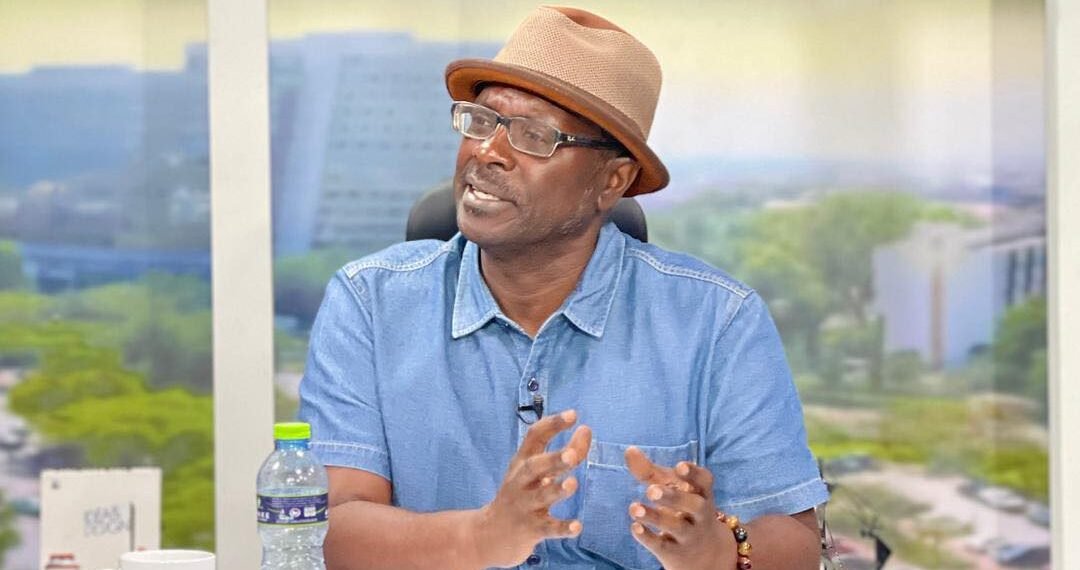

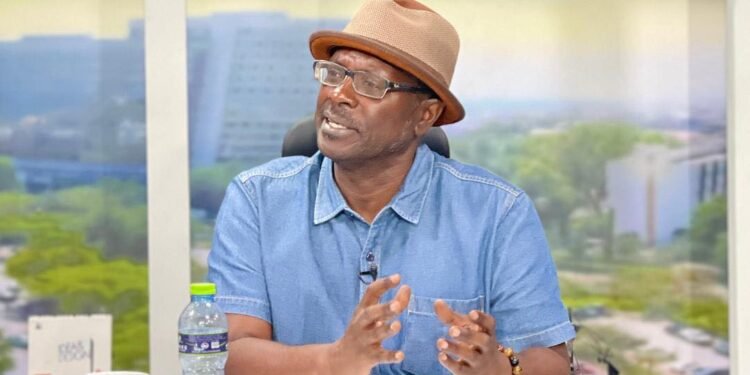

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare, CDD-Ghana Fellow

Yet he cautioned that the frequency of these actions should not be mistaken for their legitimacy or effectiveness. In his view, repetition does not confer wisdom, and the democratic costs of expulsions often outweigh any perceived benefits.

At the core of his critique is a question he said is rarely asked but urgently required. What exactly does a political party achieve by expelling a member? He stressed that this is not a rhetorical inquiry but one grounded in constitutional law, democratic theory, and political reality.

Political Parties Are Constitutional Institutions, Not Private Property

When examined closely, he argued, expulsions are largely futile, legally hollow, democratically corrosive, and politically self-defeating. Professor Asare insisted that political parties in Ghana are not private clubs or social associations that can act solely at the discretion of their executives.

“Political parties are creatures of the Constitution. Article 55 does not merely recognize them; it constitutionalizes them as essential vehicles for democratic governance. That status imposes limits.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare, CDD-Ghana Fellow

In his assessment, a party cannot enjoy constitutional privileges, public protections, and guaranteed access to state resources while simultaneously claiming the unchecked autonomy of a private association.

Once a party assumes constitutional relevance, its internal conduct inevitably acquires a public dimension. Party discipline, therefore, must be evaluated against constitutional first principles rather than internal preferences.

He further pointed to Article 55 provisions that require the state to provide fair opportunities for political parties to present their programmes to the public and ensure equal access to state-owned media for presidential candidates.

These clauses, he explained, are not concerned with internal party management but with protecting democratic choice for the electorate, insisting that political parties are constitutionally protected because they serve the public interest, not because they exist to satisfy party executives.

As a result, their internal practices cannot be treated as purely private matters. Judicial interpretation, Professor Asare argued, reinforces this position, adding that the Supreme Court has previously affirmed that matters affecting political parties are matters of public interest.

“In holding that the alleged theft of funds belonging to a political party constituted an offence against the public interest under Article 295(1), the Court emphasized the pivotal role political parties play in democratic governance and the heavy constitutional and statutory obligations imposed on them under Article 55 and PNDCL 281, including mandatory audits and public disclosure of finances (see REPUBLIC v YEBBI & AVALIFO [1999-2000] 2 GLR 5).”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare, CDD-Ghana Fellow

For Professor Asare, the implication is clear. Parties cannot claim constitutional relevance when it suits them and retreat into claims of private immunity when challenged.

Party Membership, a Constitutional Right

A central pillar of his argument concerns party membership itself. Article 55 guarantees every citizen of voting age the right to join a political party. This right, he stressed, belongs to the citizen and flows directly from citizenship.

It is not a privilege conferred by party leadership, nor is it conditional on conformity or obedience. Any attempt to erase a citizen’s political identity through expulsion, he argued, sits uneasily with this constitutional guarantee.

Drawing on comparative practice, Professor Asare noted that in some jurisdictions party membership carries tangible legal consequences. Citizens may declare party affiliation during voter registration, and participation in party primaries may be restricted to registered members.

Even in such systems, however, party affiliation is declared by the citizen, voter registration is controlled by the state, and parties cannot instruct the state to erase a citizen’s affiliation or bar a qualified voter from participating in a primary. If party control over membership is limited even in these contexts, he argued, it is even weaker in Ghana.

In Ghana’s political system, party affiliation is not recorded by the state, and voting rights are entirely detached from party membership. Not all party members vote in primaries, and primaries themselves are internal and voluntary arrangements rather than state administered civic processes.

Against this backdrop, Professor Asare questioned the practical effect of expulsion, contending that an expelled member remains on the voter register and retains the right to vote, campaign, donate, persuade others, and publicly identify with the party.

“At most, expulsion removes a person from internal offices or internal decision-making roles, and even that only if the person holds such an office in the first place.

“If expulsions have limited effect even in systems where party membership matters, then here, where party membership has no legal consequence at all, expulsion collapses entirely into symbolism.”

Professor Stephen Kwaku Asare, CDD-Ghana Fellow

He described them as expressions of displeasure that perform authority without exercising real power, leaving belief, conscience, citizenship, and the ballot untouched.

Expulsions Are Brutum Fulmen

Beyond their legal emptiness, Professor Asare warned that expulsions are politically counterproductive. Elections, he noted, are contests of numbers, not rituals of purification. Parties win by expanding coalitions, not shrinking them.

Every expulsion narrows the political tent, alienates supporters, and signals intolerance to undecided voters. Even if expulsions were lawful, which he doubts, their strategic wisdom remains questionable.

He was careful to distinguish between leadership and membership. Parties, he acknowledged, have the right to discipline or remove officers who breach trust or misconduct themselves. Leadership is a privilege tied to responsibility.

Membership, however, is a constitutional right. In his view, the boundary of legitimate discipline ends at removal from office and does not extend to erasing political identity.

Professor Asare concluded that political parties must abandon the ritual of expulsions. If expulsion cannot affect the ballot, belief, advocacy, or citizenship, then it is not discipline but theatre.

The Constitution, he argued, envisions political parties as instruments of democratic choice, not private cartels policing thought. Ghana’s democracy has matured, and its political parties, he insists, must mature with it.