A Fellow of the Ghana Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana), Dr Ohene Aku Kwapong, has thrown his weight behind the recommendations of the Constitutional Review Committee (CRC), describing the report as Ghana’s most credible attempt yet to fix what he terms the country’s “institutional plumbing.”

In an extensive assessment of the Professor H. Kwasi Prempeh-led committee’s proposals, Dr Kwapong argued that Ghana’s democratic challenges are rooted less in elections and more in the incentives embedded in the country’s political and governance architecture. According to him, many democracies across the world, not only in Africa, falter because their institutions reward the wrong behaviours.

“If you want to understand why many democracies struggle, you don’t look first at elections. You look at institutions: who holds power, how incentives are structured, and whether accountability is real or mostly theatrical.”

Dr Ohene Aku Kwapong, CDD Ghana Fellow

From that perspective, he sees the CRC report as an effort to confront long-standing distortions that have produced weak oversight, short-term policymaking and recurring governance failures.

“What makes the CRC’s recommendations noteworthy is not that they promise miracles, they don’t, but that they acknowledge a basic truth political economists have long emphasized: bad incentives reliably produce bad outcomes, even in otherwise stable democracies.”

Dr Ohene Aku Kwapong, CDD Ghana Fellow

Checking Concentration of Executive Power

Dr Kwapong noted that a central theme running through the CRC’s work is the concentration of executive power, stating that, like many constitutions drafted in the post–Cold War period, Ghana’s 1992 Constitution vests significant authority in the presidency.

While this was originally intended to ensure stability, he argued that it has gradually created distortions in accountability and governance. The CRC’s proposals, in his view, implicitly acknowledge that presidential power has become overly dominant and needs recalibration.

One of the more debated recommendations is the proposal to extend the presidential term from four to five years while maintaining the two-term limit. Dr Kwapong dismissed claims that the idea is radical, explaining that the economic logic behind it is straightforward.

Short political cycles, he argued, encourage leaders to prioritise quick, visible projects over long-term investments in areas such as education, infrastructure, and institutional reform. “When leaders are perpetually campaigning, long-term investments get crowded out,” he said, adding that a longer term modestly shifts incentives away from immediate electoral payoffs toward more durable outcomes.

He also supported the proposal to lower the minimum age requirement for presidential candidates from 40 to 30 years, describing it as a reflection of Ghana’s demographic reality rather than a symbolic gesture.

Ghana, he pointed out, is a young country governed largely by older elites, a mismatch that has political and economic consequences. Persistent exclusion of younger citizens from leadership, he warns, fuels disengagement and cynicism and can ultimately threaten stability.

Ending the Executive–Legislative Hybrid System

Perhaps the most consequential recommendation, in Dr Kwapong’s assessment, is the proposal to end the executive–legislative hybrid system that allows Members of Parliament to serve simultaneously as ministers. He described this arrangement as one that predictably weakens parliamentary oversight.

MPs who aspire to ministerial appointments, he explained, have little incentive to rigorously scrutinise the president or the executive. The result is a legislature that often functions as an extension of executive power rather than an effective check on it. In his view, restoring this separation is critical to rebuilding meaningful accountability within Ghana’s political system.

“Separating Parliament from the Executive won’t magically produce virtue. But it restores a basic democratic mechanism: the people who spend public money should not be the same people tasked with policing that spending.”

Dr Ohene Aku Kwapong, CDD Ghana Fellow

The CRC’s focus on political parties and campaign financing also receives strong backing from the CDD-Ghana Fellow. He described political parties as the least regulated yet most powerful actors in Ghanaian democracy, warning that unregulated money corrodes democratic systems faster than almost anything else.

Without transparency and enforceable limits, he argued, parties risk becoming vehicles for private interests rather than expressions of public choice, a problem that is not unique to Ghana.

Linked to this is the recommendation to limit campaign periods. Dr Kwapong observed that near-permanent campaigning distorts governance by diverting public resources, deepening polarisation, and stalling policy innovation.

He believes that shortening formal campaign periods, while seemingly modest, could yield significant benefits by allowing governments to focus more consistently on governing rather than electioneering.

Safeguarding the Independence of Constitutional Bodies

Another key area highlighted in the CRC report is the independence of constitutional bodies such as the Electoral Commission, the National Media Commission and the National Commission for Civic Education.

Dr Kwapong stressed that these institutions are not necessarily failing outright, but their appointment and funding structures leave them exposed to political pressure.

From an institutional economics perspective, he described this as a classic principal–agent problem, where bodies meant to constrain power are appointed by those they are expected to restrain. “Independence in name only is not independence,” he cautioned.

On corruption and justice, Dr Kwapong supported proposals to split the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice into separate human rights and anti-corruption bodies. He argued that anti-corruption enforcement is a specialised, full-time task and that combining it with broader mandates dilutes effectiveness.

The same reasoning, he said, applies to the recommendation to rethink the Attorney-General’s dual role as both chief prosecutor and political appointee. Conflicts of interest, he noted, are rarely solved by good intentions but by sound institutional design.

Timely Decentralization Reforms

Decentralisation reforms, particularly the election of Metropolitan, Municipal and District Chief Executives, are also framed by Dr Kwapong as an accountability issue rather than a guarantee of competence.

Appointed local executives, he argued, answer upward to the centre rather than downward to citizens, weakening service delivery and blurring responsibility. Elections, while imperfect, would at least make failure visible, which he described as a necessary first step toward improvement.

Finally, he drew attention to the CRC’s emphasis on long-term development planning and fiscal discipline. Ghana’s recurring macroeconomic instability, he argued, is often political rather than technical.

When governments can borrow freely, grant tax exemptions discretionarily and abandon development plans with each electoral cycle, fiscal crises become predictable outcomes. Embedding discipline in the constitution, he says, will not eliminate poor decisions but will raise the cost of making them casually.

Dr Kwapong is careful to temper expectations, stressing that constitutional reform rarely delivers instant transformation. However, he believes the CRC’s proposals represent something more valuable than sweeping promises.

Taken together, they are, in his words, “a serious attempt to realign incentives,” which is where meaningful progress in both economics and politics usually begins.

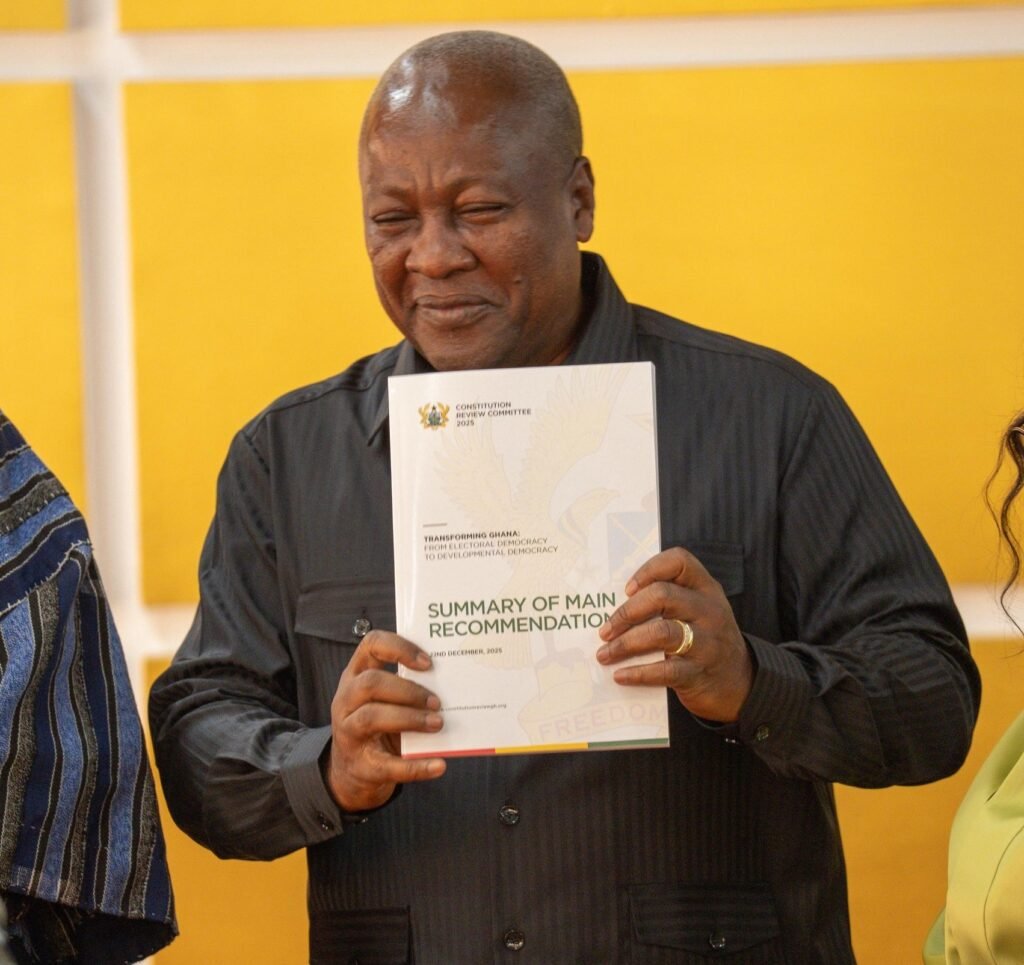

With the CRC having submitted its final report to President John Dramani Mahama and an implementation committee expected in early 2026, he suggested Ghana has a rare opportunity to translate institutional insight into lasting democratic reform.

READ ALSO: IMF’s $385m Lifeline Set to Power Ghana Cedi Rebound After Recent Slippage