Renowned data and policy analyst Alfred Appiah has criticised the previous government’s flagship health infrastructure program, calling the Agenda 111 initiative a prime example of a policy that is motivated more by procurement interests than by strategic national needs.

His critical remarks bring up important issues regarding accountability, planning, and execution in Ghana’s healthcare system.

The Agenda 111 project, spearheaded by former President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, was introduced with great fanfare and marketed as a daring attempt to close the nation’s massive healthcare infrastructure deficit.

The pledge was straightforward: to construct 111 new hospitals in areas and districts that lacked sufficient infrastructure.

However, after several years and more than $400 million, none of these hospitals are still in use. The Ministry of Health recently confirmed this startling fact.

The hospitals at Trede, Kokoben, and Ahanta are “95% complete,” according to a recent Ministry of Health’s statement, despite the revelation that they are still not operational.

Furthermore, the project’s total estimated cost has now risen to $1.589 billion, which is an astounding sum, particularly for a nation still dealing with debt problems and an ongoing IMF program.

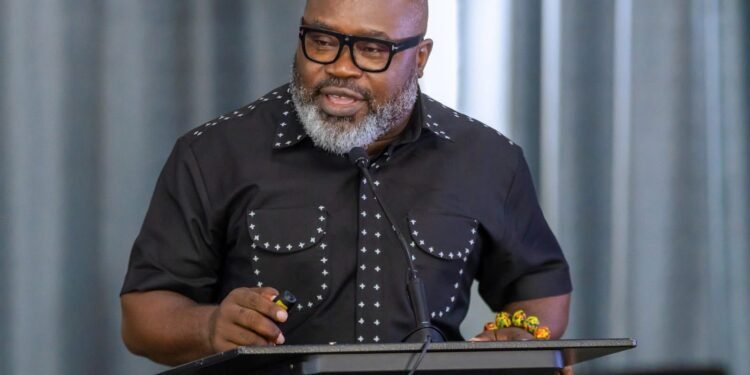

In his assessment of what went wrong, Alfred Appiah was blunt in his criticism of the previous government’s hurried implementation of the Agenda 111 initiative.

“On Agenda 111, it made absolutely no sense to try to concurrently build hospitals in every district without one, using the same model, size, and cost, especially without secured funding at inception”.

Alfred Appiah, Data and Policy Analyst

His comments strike at the heart of the problem: Both the idea and the implementation of Agenda 111 had serious flaws.

The districts of Ghana are not all the same. Their geographic size, population, and distance from current tertiary or secondary healthcare facilities all differ greatly.

According to Alfred Appiah, these variations would have been taken into account in any well-considered infrastructure plan, which would have identified priority areas through a spatial analysis.

However, Agenda 111 seemed to overlook all of these subtleties. Appiah contended that a one-size-fits-all strategy was ineffective. “The project required appropriate phasing and improved design,” he remarked.

Scattergun Strategy

Alfred Appiah also noted that the government adopted a scattergun strategy that spread scarce national resources too thinly across too many locations rather than concentrating on finishing high-potential projects like the Sewua and Afari hospitals or improving tertiary facilities that were already operational but underfunded.

He lamented that the outcome is an incomplete legacy of dispersed building sites and concrete skeletons without a clear plan for completion.

The motivation behind the entire endeavor is even more concerning. Appiah asserted that “procurement obviously drove policy, with contracts awarded en masse.”

Not only is administrative inefficiency implied here, but Appiah noted that there is also a more unsettling implication that commercial and political interests may have taken precedence over national health priorities.

The findings of the Health Harmonisation Assessment Report, which was co-commissioned by the Ghana Health Service, the Ministry of Health, the Global Fund, the World Health Organisation, and the Government of Ghana, further support this damning verdict.

Only 5% of Ghanaian consultation rooms currently have the tools required to properly diagnose patients, according to the report.

This statistic poses a risk in addition to being embarrassing. Despite hundreds of millions of dollars being invested in unfinished monuments of political overreach, it signals a public health system on the verge of collapse, devoid of essential diagnostic tools.

Appiah’s central question strikes at the heart of this issue: Who benefited in the end apart from the contractors who smiled to the bank?

Ghanaians need to insist on answers to this question. If improving access to healthcare was the goal, the result should be measured by actual, well-equipped hospitals that serve actual people, not by the number of contracts signed or buildings that have been partially constructed.

Wide-ranging effects result from this disaster, as health outcomes continue to deteriorate and confidence in the government’s capacity to carry out ambitious national projects is eroding.

Furthermore, the economic cost is growing intolerable in both opportunity and actual monetary terms as people are forced to face the sobering fact that billions of dollars have been spent, but the health system is still dangerously underfunded, disjointed, and primarily dysfunctional.

Agenda 111 may ultimately be remembered as one of the most costly examples of how public policy should not be planned and carried out.

For the present and upcoming administrations, it serves as a warning that infrastructure is more than just physical structures; it also involves the careful balancing of needs, resources, and governance.

Ghana deserved better, and the next big project could end just as badly if difficult questions are not asked and addressed.

“We spent petroleum revenues, some contractors and architects got paid, and the country is left with uncompleted buildings and no clear plan to finish and operationalise them.”

Alfred Appiah, Data and Policy Analyst

For a country battling limited fiscal space, rising healthcare demand, and widespread inequality, such alleged reckless mismanagement is not just a political failure—it is a betrayal of the people.