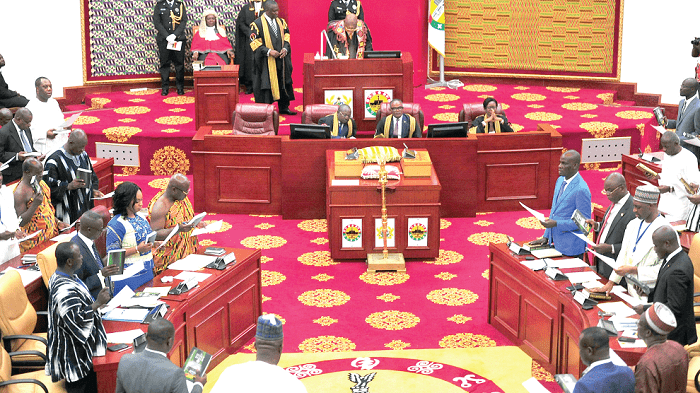

On June 9, 2025, Ghana’s Parliament sparked a nationwide debate on anti-corruption efforts by unveiling the proposed “Vulture Awards”—a controversial initiative aimed at publicly shaming the most egregiously corrupt individuals in public office.

Though dubbed a creative tool in the ongoing anti-corruption fight, the initiative has sharply divided opinion—especially among legal and governance experts.

The premise of the awards is simple: name, shame, and disgrace public officials found to be deeply corrupt. Symbolically branded with a dishonorific “vulture” title, recipients would be spotlighted for their moral decay and betrayal of public trust.

Yet, critics argue this dramatic measure risks prioritizing performance over genuine accountability.

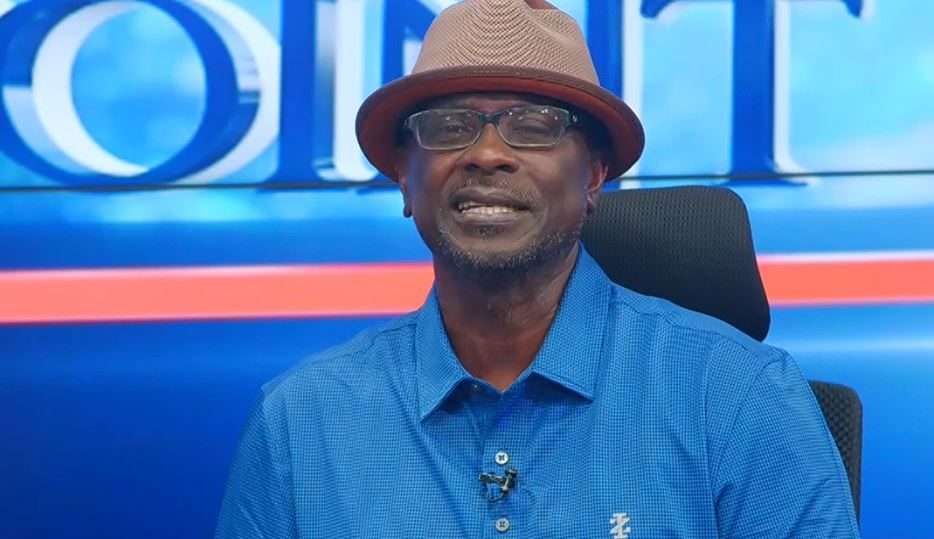

One of the strongest dissenting voices is Prof. Stephen Kwaku Asare, a legal scholar and Democracy and Development Fellow at CDD-Ghana.

While acknowledging the urgent need to tackle endemic corruption, he questioned the legitimacy and long-term impact of the proposed awards.

“On the surface, this sounds like an audacious anti-corruption initiative. After all, we live in a republic where corruption flourishes in broad daylight, and consequences rarely follow. Public ridicule could, perhaps, succeed where prosecution has failed.”

Prof. Stephen Kwaku Asare

However, Prof. Asare quickly challenged the wisdom of such theatrics. “Is this justice or jest? Accountability or theatre?” he asked, warning that turning serious criminal offenses into a satirical awards ceremony could do more harm than good.

According to him, “The danger of performance justice” lies in the fact that corruption is not just an ethical failure, but a prosecutable crime. “Turning it into an annual award show risks trivializing its devastating impact,” he added.

He pointed to the tangible consequences of corruption—crumbling infrastructure, underfunded schools, and overwhelmed hospitals—as proof that mockery cannot replace meaningful punishment.

Anti-Corruption Needs More Than Viral Moments

While the “Vulture Awards” may create viral buzz and temporarily appease public anger, Prof. Asare maintained that the initiative is unlikely to produce meaningful accountability or consequences for those involved in corruption.

He questioned whether such symbolic gestures would lead to actual convictions, asset recovery, or institutional reform, emphasizing that public shaming should only occur after due legal process—not in place of it.

He also highlighted a major weakness in the plan: the lack of a clear legal framework to guide its implementation.

“Who decides who gets this award? Without a legal framework, it opens the door to arbitrary finger-pointing, political vendettas, and reputational lynching. We risk creating a dangerous precedent: mock trials by applause.”

Prof. Stephen Kwaku Asare

Even those guilty of corruption deserve due process, he emphasized—not because they deserve protection, but because justice requires fairness and consistency.

Without this, the very legitimacy of Ghana’s anti-corruption fight could be undermined.

“Yes, vultures feast on decay. But it is not enough to name them—we must starve them, strip them of their stolen gains, and close the systems that enable them. Let us not substitute spectacle for substance.”

Prof. Stephen Kwaku Asare

He went on to propose a more comprehensive and legally grounded path to combating corruption effectively.

According to him, Parliament should start by demanding action on long-delayed prosecutions and publishing all public procurement and contract records.

It should also move to empower oversight institutions like the Auditor-General’s office, the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ), the Office of the Special Prosecutor (OSP), and the Economic and Organised Crime Office (EOCO).

Call For Real Reform, Not Public Shaming

Moreover, Prof. Stephen Asare called for new legislation on unexplained wealth, asset recovery, and campaign financing.

He suggested the enforcement of time standards in the judiciary and the imposition of surcharges on individuals who have acquired public lands, insisting they pay the full market value.“Prosecute the looters—don’t just prank them.”

Prof. Asare proposed that if awards must be given, they should honor those who contribute to justice—not those who violate it.

“Let us give awards to prosecutors who win cases, investigators who uncover the truth, and courts that deliver timely, fair judgments, not just to shame the vultures, but to honor the eagles—those who rise above fear, favor, and failure to defend justice. Celebrate integrity, not just expose rot.”

Prof. Stephen Kwaku Asare

While the Vulture Awards may attract public attention and stir national conversation, Prof. Asare’s critique underscores a deeper issue in Ghana’s anti-corruption landscape: the need for systemic reform, not symbolic gestures.

As the proposal continues to circulate within Parliament and among the public, Ghanaians are left to consider whether shaming alone is enough.

True justice, many argue, demands more than headlines, hashtags, and theatrical displays—it requires strong institutions, concrete prosecutions, and systemic reforms to tackle corruption meaningfully.

READ ALSO: Trump Hails National Guard Deployment In Los Angeles