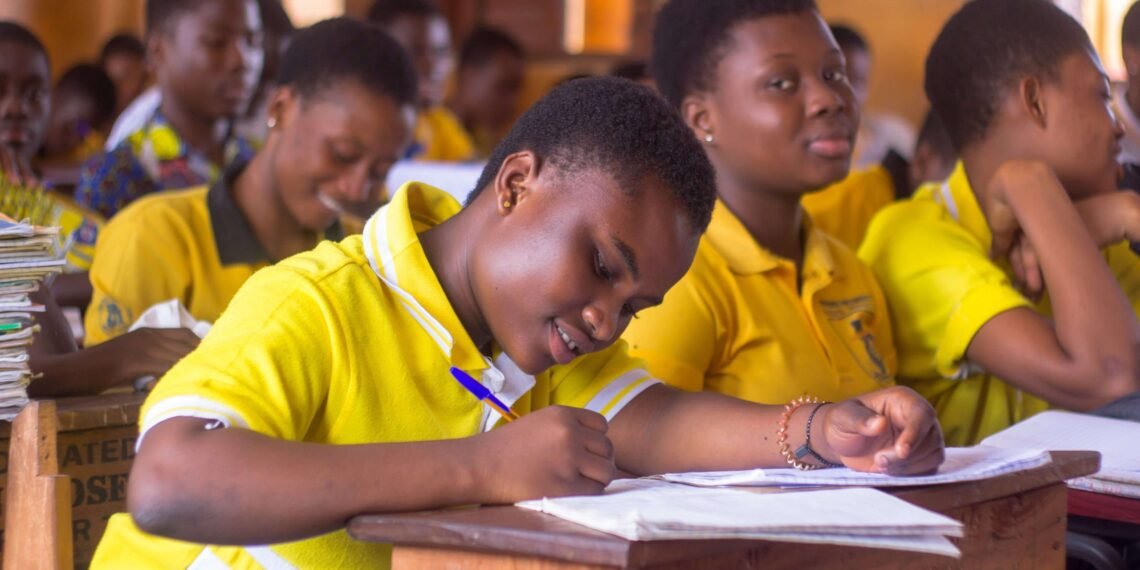

Ghana’s ambition to achieve a 90% national pass rate in the Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE) by 2025 appears increasingly out of reach, as new data reveals a steady decline in performance across both deprived and endowed districts.

Despite over US$200 million invested under the Ghana Accountability for Learning Outcomes Project (GALOP), pass rates have dropped consistently since 2021, raising urgent questions about the effectiveness of current interventions and the glaring inequities in the education system.

The latest policy brief by Africa Education Watch (Eduwatch), titled “Declining BECE Outcomes: Are Interventions Missing the Mark?”, paints a grim picture of Ghana’s basic education sector.

The report highlighted a national decline in BECE pass rates, with deprived districts falling from 81.01% in 2021 to 75.65% in 2024, while endowed districts dropped from 90.19% to 86.84% over the same period.

Even more alarming is the widening gap between these districts, from 9.18 percentage points in 2021 to 11.19 in 2024—a trend that underscores deepening disparities in access to quality education.

“The numbers are a wake-up call. We’re pouring resources into the system, but they’re not reaching the schools and students who need them most. Without targeted, equity-driven financing, Ghana risks leaving an entire generation of children behind.”

Africa Education Watch

A Tale of Two Districts: Bongo’s Struggle Reflects Broader Failures

The report singles out the Bongo District as a microcosm of the crisis. Here, BECE pass rates plummeted from 56% in 2021 to a staggering low of 32% in 2023, with only a slight recovery to 40% in 2024.

This is less than half the average pass rate for endowed districts, a disparity attributed to severe resource shortages.

Field surveys reveal that only 2% of schools in deprived districts have access to ICT facilities, 42% lack core subject textbooks, and just 37% have electricity, a basic necessity for science and computer labs. In Bongo alone, 3,000 pupils lack desks, and many more study without adequate learning materials.

“How can we expect children to excel when they’re sitting on floors, sharing tattered textbooks, or learning in darkness? The infrastructure deficit in deprived areas is a national embarrassment. It’s no surprise that performance is collapsing.”

Africa Education Watch

The GALOP initiative, launched in 2020 to improve learning outcomes through teacher training, digital content, and performance-based grants, has failed to reverse the decline. Critics argue that the program’s top-down approach neglects grassroots realities.

“GALOP’s design is flawed. Throwing money at teacher workshops or tablets won’t work if schools don’t have electricity or if supervisors aren’t visiting classrooms to ensure quality teaching. We need systemic reforms, not piecemeal projects.”

Africa Education Watch

Political Promises vs. Budgetary Neglect

The current administration has declared basic education a priority, but the sector received just 21% of the total education budget for 2025, far short of the 40% recommended by Eduwatch.

According to the report, this underfunding perpetuates a cycle of neglect, particularly in deprived districts where schools struggle with overcrowded classrooms, unmotivated teachers, and crumbling facilities.

“The government talks about equity, but the budget tells a different story. We haven’t seen the 20% deprived area allowance promised to teachers here. Many of my colleagues transfer out as soon as they can, leaving students with untrained substitutes.”

Africa Education Watch

Teachers in underserved areas also face immense challenges, from inadequate supervision to a lack of incentives. The report noted that School Improvement Support Officers (SISOs) and District Education Teams are under-resourced, leaving schools without accountability mechanisms to ensure effective teaching.

A Path Forward: Equity, Accountability, and Systemic Reforms

Eduwatch’s policy recommendations urge immediate action to address the crisis. Key proposals include increasing basic education’s budget share to 40%, prioritising deprived districts for infrastructure investments, and ensuring the timely provision of textbooks and STEM facilities.

The report also calls for stronger teacher supervision and ICT integration, including internet access and digital devices.

“This isn’t just about money—it’s about how we spend it. Targeted investments in school furniture, electricity, and teacher motivation can transform learning outcomes. But we need political will to make it happen.”

Africa Education Watch

Stakeholders are now pressuring the Ministry of Education to act. The Ghana Education Service (GES) has pledged to review supervision frameworks and accelerate textbook distribution, but advocates demand faster, bolder steps.

“We’re running out of time. If Ghana is serious about the Education Strategic Plan’s 2030 targets, we must confront these inequities head-on. Otherwise, the BECE decline will become a national catastrophe.”

Africa Education Watch

The declining BECE pass rates are more than a statistic—they reflect a failing system that risks derailing Ghana’s human capital development. As the gap between deprived and endowed districts grows, the urgency for reform intensifies.

“Education is the bedrock of our future. If we don’t fix this now, we’re condemning thousands of children to a lifetime of missed opportunities,” the report concluded

READ ALSO: Africa Urged to Add 16 GW of Annual Power to Meet Energy Needs