Ghana’s education sector is facing a multifaceted crisis that threatens the future of its youth and the nation’s development amid what several expert consider as severe financial woes.

The delayed release of WASSCE results in addition to CETAG’s threat of an industrial action over unmet promises are emblematic of deeper systemic issues that require urgent redress.

Commentaries by leading academics and professionals, coupled with warnings from key stakeholders, paint a picture of a sector struggling under the weight of neglect, mismanagement, and insufficient funding.

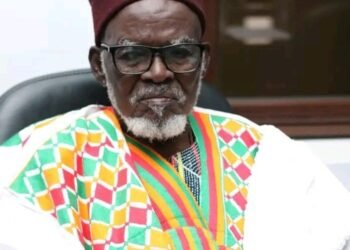

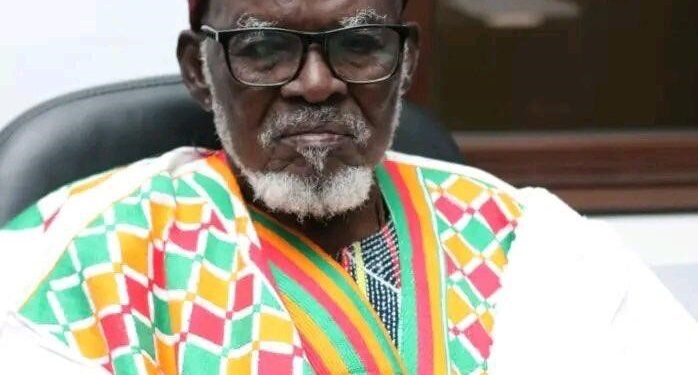

Professor Ernest Kofi Abotsi, Dean of the UPSA Faculty of Law, in very scathing critique, succinctly underscored the danger that is ahead if urgent actions is not taken by the government.

“The delayed release of WASSCE results is symptomatic of deeper crises in the educational sector. Low morale of teachers, politicization, underinvestment, and facility deficits reflect a system that has been toyed with, and we may be on a dangerous precipice.”

Professor Ernest Kofi Abotsi, Dean of UPSA Faculty of Law

His words resonate with the dire warning from the Conference of Heads of Assisted Secondary Schools (CHASS), which cautioned that secondary schools may not reopen on January 3, 2025, unless outstanding funds are released.

These challenges expose the sector’s structural weaknesses, which are exacerbated by years of inadequate policy direction and funding.

The Free SHS Dilemma

The Free Senior High School (SHS) policy, once hailed as a revolutionary initiative to expand access to education, has become a subject of contentious debate.

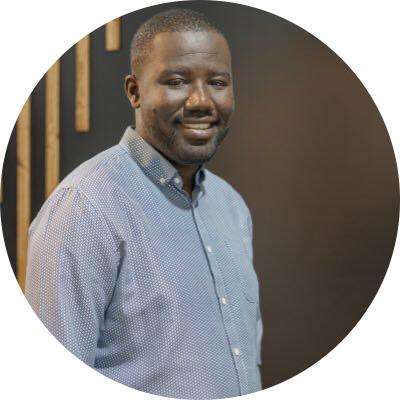

Alfred Appiah, an Applied Economist and Data Analyst, highlighted the critical funding shortfalls that has plagued the policy, asserting that even though the government allocates funds in the budget to the program, it is only able to release about half of the allocated funds (as of 2021/22).

Mr Appiah’s analysis revealed a disturbing trend with him pointing out that in 2023, out of the allocated 2.96 billion cedis for Free SHS—funded through petroleum revenue—only 850 million cedis were disbursed.

This amount, he noted was significantly lower than the 1.2 billion cedis released in 2022, despite rising enrollment and inflation.

“How are schools supposed to run effectively under such circumstances? If government can only truly afford half of the money required to run free SHS, why shouldn’t there be a review and targeting through means testing? Why continue in this charade of free for all when the schools are struggling to run?”

Alfred Appiah, Applied Economist and Data Analyst

The underfunding according to Mr Alfred Appiah has left schools grappling with operational inefficiencies, justifying his call for a review of the Free SHS model, including means-testing to target the most vulnerable.

His sentiments echo the concerns of many education advocates who argue that universal free education—without sustainable funding—is unsustainable and counterproductive.

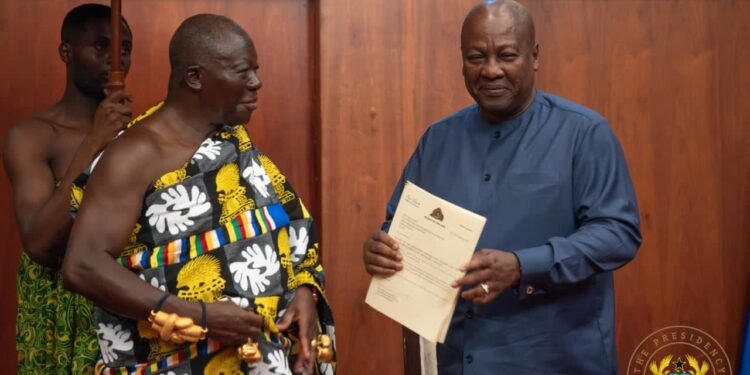

In an earlier statement, President-Elect John Dramani Mahama acknowledged the challenge facing the country’s educational sector, attributing the sector’s financial constraints to the absence of consistent and dedicated funding mechanisms.

His critique reflects a broader leadership vacuum in addressing the perennial issues plaguing Ghana’s education sector. The reliance on petroleum revenue, which is subject to market volatility, further underscores the need for innovative and stable funding sources.

The crisis in Ghana’s education sector is a ticking time bomb. The delayed release of WASSCE results, funding shortfalls, and threats of school closures are not isolated incidents but symptoms of a broken system.

The country’s leaders must heed the warnings of experts like Professor Abotsi and Alfred Appiah and take decisive action to safeguard the future of Ghana’s youth. Anything less would betray the trust and aspirations of millions of Ghanaian students and their families.

READ ALSO: GUTA Bemoans High Cost of Doing Business in Ghana