Southern Africa, long regarded as a bastion of democratic stability, witnessed a seismic political shift in 2024.

Liberation-era parties that had governed for decades faced historic defeats or narrowly held onto power as frustrations over economic hardships and lack of opportunities surged, especially among the region’s youth.

While other parts of Africa contend with military coups and violent power struggles, Southern Africa’s elections were marked by peaceful transitions but also growing discontent.

For many voters, particularly younger ones with no personal memory of colonial rule, the achievements of liberation movements no longer carry the same weight.

“Generational change is an important factor in the shifting political tectonic plates we are seeing,” said Nic Cheeseman, a political scientist at the University of Birmingham. “People want jobs and dignity — you can’t eat memories.”

Botswana delivered one of the year’s biggest surprises when opposition parties ended the Botswana Democratic Party’s (BDP) 58-year reign.

The BDP, which had governed since independence in 1966, suffered a landslide defeat in October as the nation grappled with youth unemployment and a sluggish economy driven by reduced global demand for diamonds.

Opposition supporters dressed in blue and white flooded the streets to celebrate as then-President Mokgweetsi Masisi conceded defeat even before the vote count was completed.

South Africa also experienced a major political transformation in May. The African National Congress (ANC), the party of Nelson Mandela, lost its parliamentary majority for the first time since the end of apartheid in 1994. Forced into a coalition, the ANC’s support plummeted from 57.5% in 2019 to 40%, amid widespread discontent over corruption, failing public services, and persistent economic woes.

The result marked an uncharted political path for South Africa, signaling the public’s growing impatience with liberation-era leadership.

Namibia’s ruling South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO) narrowly avoided a similar fate. Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah made history by becoming Namibia’s first female president, but SWAPO won only 51 parliamentary seats — just enough to maintain its majority.

This marked the party’s worst performance since independence in 1990, underscoring a shifting political landscape.

Nicole Beardsworth, a political researcher at the University of the Witwatersrand, noted that the region’s stable democratic processes offer hope but pose challenges for ruling parties. “What we see in Southern Africa is a relative stability in terms of democratic standards, where citizens seem to believe that their votes matter and that they count,” she said.

Not all transitions were peaceful. In Mozambique, the governing Frelimo party extended its nearly 50-year hold on power following an October election, sparking deadly protests.

Amnesty International reported at least 100 fatalities as demonstrators took to the streets. Opposition leader Venancio Mondlane, currently in exile, has rejected the results and continues to call for demonstrations.

Mozambique’s unrest mirrored tensions elsewhere. In Comoros, violent protests erupted after President Azali Assoumani secured a fourth term in January, leaving one person dead and dozens injured.

Cheeseman noted that such protests reflect a growing dissatisfaction even in countries where democracy is under strain. “Even citizens who have lost faith in democracy want responsive and accountable government, and to have their voices heard,” he said.

Shifts Across The Continent

Southern Africa’s political upheavals echoed broader trends across the continent. Mauritius, often hailed as Africa’s most stable democracy, saw its opposition coalition sweep parliamentary elections, ending the tenure of Pravind Jugnauth. In his place, former Prime Minister Navin Ramgoolam returned to power.

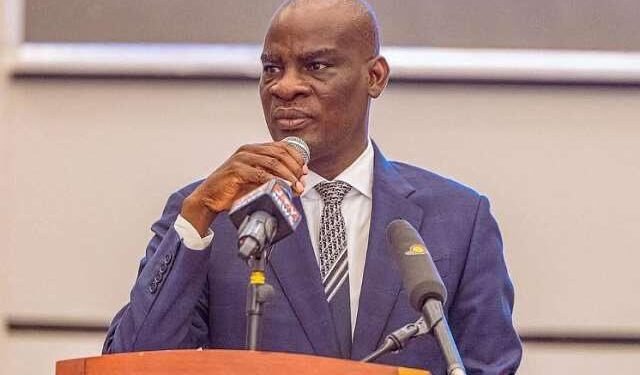

Elsewhere, Ghana witnessed a comeback by former President John Dramani Mahama, whose National Democratic Congress secured both the presidency and a parliamentary majority in December. The election reflected voter frustration with outgoing President Nana Akufo-Addo’s policies.

In Senegal, Bassirou Diomaye Faye became Africa’s youngest leader at 44, winning the presidency in March just weeks after his release from prison. His victory energized a population where 60% are under 25 and many work in informal jobs.

The 2024 elections have cast doubt on the future of long-dominant liberation movements in Southern Africa. Despite their role in securing independence, these parties face growing pressure to address contemporary challenges, particularly from younger voters.

As Beardsworth highlighted, “This does present a concern for ruling parties,” noting that citizens in Southern Africa increasingly expect results over rhetoric.

Whether these shifts signify a permanent reordering of the region’s political landscape or a temporary wake-up call remains uncertain. What is clear, however, is that voters are demanding accountability and progress, signaling the end of unquestioned loyalty to liberation-era parties.

READ ALSO: NPP’s Decline Tied to Constitutional Breaches, Lack of Discipline