Highlife music, a genre that originated in Ghana in the early 20th century, has long been celebrated as a quintessential expression of Ghanaian culture and identity.

Characterized by its rich blend of traditional Akan melodies and Western musical elements, highlife has played a pivotal role in the social and political fabric of Ghana.

However, in recent years, many have lamented the decline of highlife, declaring it “dead” in the face of the meteoric rise of genres such as Afrobeats and hip-hop.

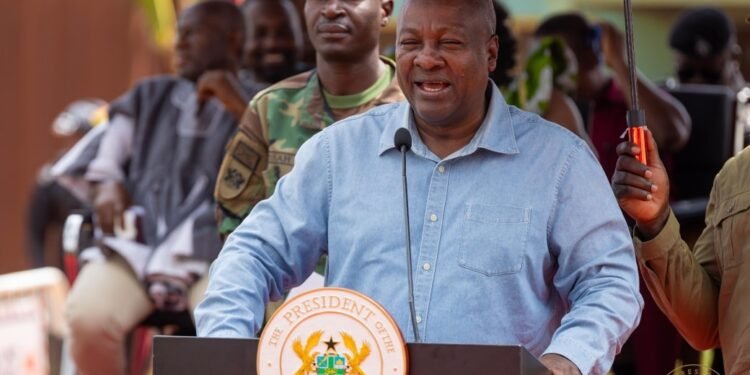

Highlife’s future is once again on the chopping block, and this time, music producer Kwame Yeboah has stated that the genre is “dead” in Ghana.

Kwame Yeboah said the live production of Highlife has been replaced by computer-produced sound, with many of today’s “Highlife” artists relying on programmed beats instead of the live instruments that once gave the genre its magic.

According to him, the switch has stripped away the unique sound that made Ghana stand tall on the global music scene.

“Highlife music is dead in Ghana. Santrofi, not in Ghana. Do you understand what I mean by it’s dead in Ghana? Kuami Eugene is not a big export because the music he is doing is computer-based. If you play Santrofi’s song and you play Kuami Eugene’s song, you can hear what I mean. One of them is played with live instruments, and one of them is played with computers.”

Kwame Yeboah

Kwame Yeboah explained that while it’s possible to program Highlife on a computer, it does not give the international audience anything fresh.

“Well, you can, but then again, is that AI music or what is that? What are we again? What do we have to show the world? As Ghanaians, what do we have to show the world? Computer? What do we have that the world will value as something different? Computers are everywhere in this world. Isn’t it our instruments that we have here? So if we don’t play those instruments, how are they going to hear something different?”

Kwame Yeboah

The producer notes that just as Ghanaians enjoy the unique sound of Western music, foreigners are equally fascinated by authentic Ghanaian live-instrument performances.

“We hear the music they do from there, and it sounds nicer because it’s different. And then, when they hear Wulomei and they hear other things, they think it’s amazing because they don’t hear that sound anywhere.”

Kwame Yeboah

In recent years, Ghana’s musical landscape has witnessed a seismic shift, with Afrobeats and hip-hop gaining immense popularity among the youth.

Artists like Burna Boy and Wizkid have brought African music to a global audience, leading many to believe that highlife has lost its relevance. Yet, this perspective overlooks the fact that music is inherently dynamic, continually evolving in response to cultural and societal changes.

Highlife music is not so much dead as it is in a state of transformation, blending with contemporary genres to create a hybrid sound that resonates with younger audiences.

Evolution of Highlife Music

Today, many artists are infusing highlife elements into Afrobeats and hip-hop, creating a new sound that pays homage to the genre’s roots while embracing modern influences.

Musicians like Kuami Eugene, KiDi, and Adina are prime examples of this evolution, incorporating highlife rhythms and melodies into their songs, thereby ensuring that the essence of highlife remains intact.

Collaborations between traditional highlife musicians and contemporary artists further highlight this fusion, showcasing the genre’s adaptability and relevance in today’s music scene.

The decline of highlife in its traditional form does not signify the end of its cultural significance; rather, it marks a shift in its expression. Instead, it reflects the ongoing dialogue between generations and the evolution of culture.

Highlife remains a vital part of Ghanaian identity, serving as a reminder of the country’s rich musical heritage. As new generations embrace and reinterpret highlife, the genre continues to thrive in a modern context.

Moreover, the resurgence of interest in traditional music forms, spurred by movements advocating for cultural preservation, suggests that highlife’s legacy is far from extinguished.

Festivals, workshops, and educational programs focusing on highlife music further promote its appreciation among younger audiences, ensuring that the genre remains a living part of Ghana’s cultural landscape.

The assertion that highlife music is dead in Ghana overlooks the complexities of cultural evolution. While the genre no longer dominates the airwaves as it once did, it is very much alive, adapting to new musical trends and continuing to influence the cultural identity of Ghanaians.

As highlife evolves, it retains its significance, proving that music, much like culture itself, is a living entity that thrives on change.

Rather than mourning the death of highlife, Ghanaians should celebrate its resilience and embrace the new forms it takes in the vibrant tapestry of Ghanaian music.

READ ALSO: Helicopter Crash Probe to Be 70–80% Complete by August 15 – Security Consultant