Ghana’s push to digitalise its healthcare system has once again ignited debate over governance, accountability, and policy coherence.

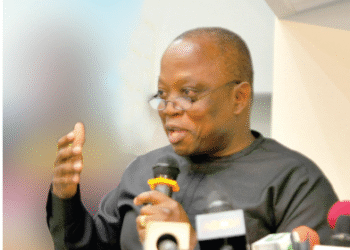

Bright Simons, Vice President of IMANI Africa, has sharply criticised the country’s approach to healthcare digitalisation, describing the ongoing cycle of system failures, contract disputes, and political interference as the latest symptom of what he calls “katanomics” – policymaking devoid of learning and accountability.

According to Mr. Simons, Ghana’s current struggle between the defunct Lightwave Health Information Management System (LHIMS) and the newly introduced Ghana Health Information Management System (GHIMS) reflects a deeper institutional weakness.

“Ghana doesn’t only struggle with the ‘how,’ its elites simply can’t keep track of why the ‘hows’ always end up being a mess. Even though IMANI flagged all the key issues in the LHIMS saga 4 years back, the current debate doesn’t even feature the critical issues. So, let me recap”

Bright Simons, Vice President of IMANI Africa

The IMANI Vice President recounted that the Lightwave project began as a $100 million contract to digitalise over 900 hospitals and clinics nationwide.

Lightwave, a Ghanaian-owned startup with no national-scale project experience, was awarded the contract in partnership with Plus91, an Indian company that had modest funding and had previously built health management software under the MediXcel brand.

Mr. Simons noted that while India built a robust regulatory ecosystem through its Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM), Ghana took a shortcut. The Ministry of Health, under the previous administration, directed all public facilities to adopt a rebranded version of MediXcel called LHIMS – bypassing innovation, competition, and existing service providers.

He described this as a “politically-driven decision,” that ignored years of innovation by local developers and led to the collapse of smaller digital health initiatives. “Innovators that had spent years building relationships with facilities and customising solutions to serve their unique challenges were thrown out into the streets,” Simons lamented.

Government Change and Fallout

Following the December 2024 elections, President John Dramani Mahama’s administration inherited the Lightwave contract amid growing complaints of system failures and billing malpractices.

The new government accused Lightwave of completing only 50% of its contractual obligations despite receiving 77% of the funds and of being responsible for data breaches that compromised patient records.

In response, the Ministry of Health awarded a new $50 million contract to Axon, a company with limited experience in digital health, to develop a replacement platform – GHIMS – a move which has reignited debate about Ghana’s pattern of discarding old systems rather than reforming them.

“I call this whole trend of policymaking, “katanomic.” Political decision-makers exercise power without real policy guardrails. They often make catastrophic mistakes, and yet there is no “national learning”, so the same mess seems to loop endlessly”

Bright Simons, Vice President of IMANI Africa

The IMANI Vice President proposed that the state’s role should be limited to “regulating interconnection systems,” rather than controlling the service delivery layer. According to him, certified digital health providers should be allowed to compete for facility contracts under clear regulatory oversight.

“The state should only get involved in licensing providers to offer interconnection to certified service delivery apps that meet standards set by a national regulator,” he explained. Mr. Simons argued that hospitals already digitalised should have the freedom to choose between providers such as Lightwave, Axon, or others, based on performance and cost efficiency.

Under such a model, competition would improve service quality and transparency, unlike the centralised, monopoly-driven model currently in place. He added that in the current arrangement, private health facilities, laboratories, and pharmacies remain excluded, making integration across Ghana’s health ecosystem nearly impossible.

Breaking the Cycle

Mr. Simons said effective digitalisation requires a long-term vision supported by multiple innovators working across different levels of healthcare delivery but within a regulated, interoperable system.

Ghana, he stressed, cannot afford to continue its pattern of politically-driven monopoly contracts that deliver limited results. “The last thing you need is a monopoly player hand-picked by a politician,” he warned.

He noted that Ghana’s digital health policy has existed for over a decade, but the absence of sustained momentum and meaningful accountability “has turned major investments into political showcases rather than functional systems.”

Bright Simons further added that Ghana’s recurring digital health failures demonstrate how buzzwords like “digitalisation” can mask a lack of genuine policy progress. “The money and the power is not invested for policy traction but for ‘state enchantment’ – the semblance of great progress,” Mr. Simons argued.

He concluded that real change will only come when citizens begin to question political narratives and demand evidence-based policymaking. “That is how a society transcends katanomics,” he said, warning that until then, Ghana’s digital health landscape would continue to cycle between optimism and disappointment.

READ ALSO: Orbán To Visit Washington For Meeting Aimed At “Complete Review” Of US-Hungarian Relations