Private legal practitioner Ace Ankomah has ignited a fierce debate on institutional independence, arguing that the recent push in Parliament to abolish the Office of the Special Prosecutor (OSP) is merely the latest manifestation of a long-standing hostility among lawmakers toward autonomous state bodies.

Ankomah used this political tussle as the basis for his radical proposal: the dissolution of the OSP, the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), and the Economic and Organised Crime Office (EOCO) to form a single, politically insulated National Prosecutions Authority.

“In my view, Parliament passing the OSP Act is the biggest concession that, when it comes to corruption and corruption-related offences, the AG’s office has not done well”

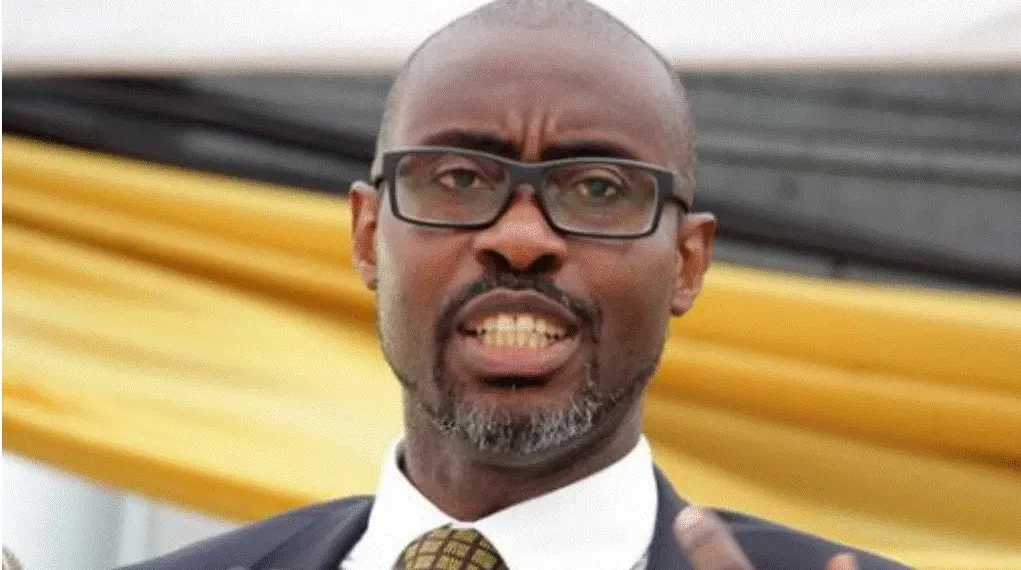

Ace Ankomah, Private legal practitioner

His comments come against the backdrop of renewed calls by the Majority Caucus, led by Majority Leader Hon. Mahama Ayariga, to scrap the OSP and return its mandate to an under-resourced Attorney-General’s Department.

Speaking in an interview, Mr. Ankomah offered a broader, historical context for this aversion, stressing that it inhibits the institutional growth critical for effective anti-corruption and accountability in the country.

Mr. Ankomah argued that Parliament’s current posture toward the OSP reflects a deep-seated institutional resistance to constitutional autonomy. He claimed that this “great aversion” is not new, citing the turbulent history of the Auditor-General’s Office as the primary evidence of Parliament’s reluctance to allow state bodies to fully assert their constitutional powers.

He recalled that “for years after the 1992 Constitution came into effect, the Auditor-General failed to exercise the critical powers of disallowance and surcharge.” It took direct legal action by pressure groups, including Occupy Ghana, to compel the office to enforce its mandate through a court order.

“Once the Auditor-General began actively enforcing these powers, the results were dramatic. According to data cited from the World Bank, the former occupant of the office, Daniel Domelevo, recovered approximately GHS 65 million for the state before his controversial removal”

Ace Ankomah, Private legal practitioner

Ankomah pointed to subsequent parliamentary debates aimed at circumventing the Supreme Court decisions that had strengthened the Auditor-General’s independence as clear proof that whenever an independent institution begins to show teeth, Parliament tends to react negatively and anti-autonomously.

AG’s Failure

Ankomah asserted that the OSP was born out of necessity, not convenience.

He contended that the Attorney-General’s office, which previously handled corruption and economic crimes, had historically struggled to deliver justice in complex and high-stakes cases, often succumbing to political interference.

He maintained that history carries proof that the politically controlled AG’s office had failed in its duty to effectively prosecute complex economic crimes.

The practitioner argued that political interference, evidenced by successive incoming administrations filing nolle prosequi to discontinue politically sensitive ongoing cases, completely undermines public confidence and the integrity of the justice system.

He stressed that Ghanaians “cannot trust any government with criminal prosecutions” because of the historical pattern of favoritism shown toward political allies.

To permanently solve the dilemma of political control and institutional weakness, Mr. Ankomah proposed a radical and comprehensive institutional reform. He called for a constitutional review of Article 88(3) and (4) to separate the criminal prosecution function entirely from the political office of the Attorney-General.

His core proposal is to merge the prosecutorial wing of the Attorney-General’s office – the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) – with the OSP and the Economic and Organised Crime Office (EOCO) to create a single, powerful National Prosecutions Authority.

This new authority, he argued, must enjoy judicial-quality independence, meaning its leadership – preferably headed by a civil servant – must be shielded by security of tenure, financial autonomy, and total insulation from political influence.

“Yes, the police will still investigate crime, but this office will be the authority to prosecute so that we can be sure there is minimal political interference”

Ace Ankomah, Private legal practitioner

By concentrating the prosecution of serious crimes in a single, politically detached body, Ankomah believes Ghana can finally achieve the institutional accountability it needs, rather than continually wasting time dismantling crucial offices simply because they are still undergoing the necessary processes of institutional learning and development.

READ ALSO: Ghana Adjusts Gradually to Green Jobs to Promote Economic Resilience