Dr. Manaseh Mawufemor Mintah, environmental law and justice expert, has warned that Ghana must resist any pressure to blindly take decisions in its lithium management.

He stressed that while the discovery of lithium at Ewoyaa is undeniably valuable, any rushed agreement, particularly the one initially structured for the Ewoyaa project, risks permanently damaging the nation’s long-term economic prospects.

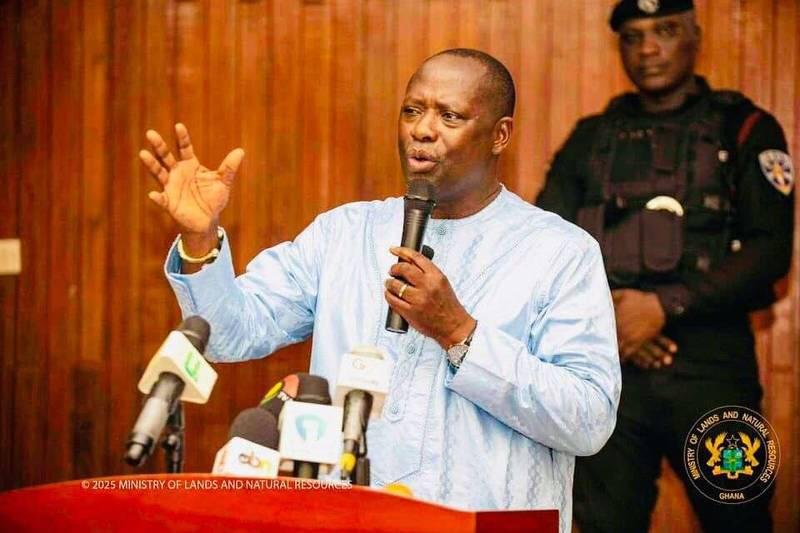

“Countries are scrambling to secure lithium, the mineral that powers electric vehicles, global battery technologies, and the future of renewable energy. But Ghana must resist the pressure to run blindly. Minerals do not expire.”

Dr. Manaseh Mawufemor Mintah

According to Dr. Mintah, a mineral’s value does not decay, but a bad mining agreement can inflict irreversible national loss, echoing the ancient wisdom that “the forest does not run away,” but a nation’s opportunity might.

Despite the government securing a 13% free carried interest and an additional 6% equity through the Minerals Income Investment Fund (MIIF), this combined 19% still leaves the state with a minority stake and limited control over the operational and pricing dynamics.

These structural flaws expose Ghana to volatile market swings and a revenue model that could “evaporate whenever markets turn.”

“Mining is a robber industry. Once the resource is taken, it is gone forever, and only the environmental scars remain. Ghana cannot afford to misfire at this moment,” Dr. Mintah warned.

Flaws in the Ewoyaa Deal Structure

The controversy surrounding the Atlantic Lithium agreement stems from fundamental structural weaknesses that critics argue replicate historical mistakes in Ghana’s extractive sector.

The initial negotiation, conducted when lithium prices were soaring above $2,800 per tonne, included a 10% royalty and the 19% state equity.

However, when prices plummeted to around $900 per tonne, the company sought to renegotiate, resulting in the government laying before Parliament a revised agreement that included a royalty rate of a static 5%, albeit with a clause to increase it if prices recover.

This revision immediately triggered widespread public debate, with policy think tanks like IMANI Africa calculating that the royalty cut transfers approximately $17.5 million annually from state revenues to company shareholders, even as their analysis shows the company would still earn a substantial gross profit of roughly 30% per tonne at the prevailing lower market price.

The reliance on the company’s “realized sales price” without an independent benchmark further compounds the risk of revenue loss, particularly when foreign partners like Piedmont Lithium are major offtakers, potentially profiting through internal pricing arrangements, a practice known as transfer pricing.

The most critical deficiency, however, lies in the lack of a firm, mandatory value addition clause.

The real wealth in the lithium value chain is not in digging up raw spodumene concentrate, but in its downstream processing into battery-grade chemicals like lithium hydroxide or lithium carbonate, which can be worth up to twenty times the value of the raw mineral.

The initial agreement’s commitment to only a scoping study for a refinery is deemed too weak. Dr. Mintah’s position aligns with the view that “without a refinery clause, without mandatory value addition… Ghana will capture little more than crumbs while others feast.”

This vision shortfall means Ghana risks surrendering the high-value industrial future of its children for “short-term revenue controlled by foreign entities.”

Parliament’s decision to withdraw the agreement was, therefore, not a delay but an essential “act of national protection” to correct these foundational weaknesses and ensure the laws, such as Act 703, are modernized to match the nation’s ambitions for critical minerals.

Cautionary Tale of Zimbabwe

Dr. Maneseh Mintah also warned that Ghana must heed the cautionary lesson provided by its continental counterpart, Zimbabwe, a country which also discovered significant lithium deposits but “chose speed over structure.”

He points out that Zimbabwe’s hasty agreements have led to over ninety percent of its lithium fields now being controlled by Chinese companies, with the nation securing only a meagre five percent royalty.

This low royalty, combined with the lack of mandatory value addition, means Zimbabwe exports raw spodumene concentrate at approximately $300 per tonne, while the refined battery-grade chemicals manufactured elsewhere fetch up to $20,000 per tonne.

As one Zimbabwean miner lamented, “We have lithium, but lithium does not have us,” perfectly encapsulating the outcome of a flawed approach where the nation captures minimal benefit from a strategic resource.

The structural failure in Zimbabwe directly highlights the need for a comprehensive critical minerals framework in Ghana that goes beyond just royalty rates and equity stakes.

It must enforce rigorous environmental protections to manage the “immense water consumption, chemical processing, tailings dams, and long-term waste management” associated with lithium mining.

More crucially, the framework must mandate and secure downstream capacity, including refineries, battery precursor plants, and technology partnerships.

Dr. Mintah insists that upstream extraction alone will never transform Ghana; true industrial transformation lies in seizing the downstream processing opportunity.

The nation has a singular chance to get its lithium governance right, and doing so requires walking with intention, firmness, and clarity, ensuring that Ewoyaa does not become another corridor of environmental damage and economic marginalization.

Pathways to Securing Ghana’s Future

To avoid the Zimbabwean predicament, the path forward must prioritize a renegotiation that guarantees long-term national interest over short-term revenue.

Parliament must insist on: a binding feasibility study for a local lithium refinery within a defined timeframe, not just a scoping study; a revised fiscal regime with adaptive royalty bands that adjust automatically with market conditions; and the formal creation of a Critical Minerals Framework that transcends existing general mining laws.

Furthermore, all agreements must include robust community safeguards, environmental bonding, and iron-clad local participation provisions. Dr. Mintah’s core message is unequivocal: “We must not give the people temporary relief at the cost of permanent national loss.”

The temporary withdrawal of the lease provides a crucial window for Ghana to implement the wisdom that the “opportunity will not” last if the initial shot is misfired.

READ MORE: Ghana Hosts Colombia’s Vice President as Both Nations Expand Strategic Ties