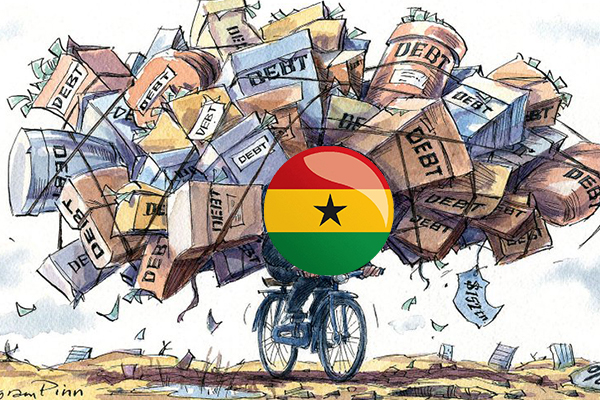

For over three decades, Ghana’s Fourth Republic has teetered on the edge of economic instability, a precarious position reminiscent of the fiscal crises that precipitated the collapse of previous republics.

Despite numerous initiatives aimed at reforming public financial management (PFM), the nation continues to grapple with systemic inefficiencies and fiscal indiscipline.

This persistent failure to implement effective reforms is akin to “playing with hellfire,” as aptly described by Franklin Cudjoe, Founding President and CEO of IMANI Centre for Policy and Education..

“To be honest, though, the country has not been short of theatrics, earnest proclamations, and acronyms in the seeming quest to redress the perennial public financial management mess.

“From PAMSCAD to PURFMAP and from BPEMS to GIFMIS, Ghana can count itself as a contender in any contests of chefs when it comes to cooking new schemes with fancy acronyms to tame the monster. Someone quipped recently that the only acronym we have yet to try is BOFROT.”

Franklin Cudjoe, Founding President of IMANI Centre for Policy and Education

According to Mr Cudjoe, each initiative has predominantly relied on enhancing bureaucratic efficiency through stringent controls and restraints.

However, this approach has often resulted in a convoluted and opaque governance system, further empowering bureaucratic insiders and exacerbating the very issues these reforms sought to address.

At the heart of Ghana’s PFM woes lies the classic principal-agent problem. In this scenario, Mr Cudjoe opined that the principals (citizens) delegate authority to agents (politicians and bureaucrats) with the expectation that the latter will act in the public’s best interest.

However, Mr Cudjoe noted that misaligned incentives and information asymmetry often lead agents to prioritize personal gains over public welfare.

In response, principals impose additional checks and controls, which can become cumbersome and counterproductive, further entrenching inefficiencies.

Reimagining Incentive Structures: Extrinsic vs. Intrinsic Motivation

The Founding President of the leading policy think-tank strongly emphasized that addressing this misalignment necessitates a reevaluation of the incentive structures governing public officials.

He pointed out that extrinsic motivation, such as competitive salaries and benefits, has been challenging to implement due to fiscal constraints and political reluctance.

Consequently, fostering intrinsic motivation—cultivating a genuine sense of pride and commitment to public service—emerges as a viable alternative.

“One can look at the Singaporean model for inspiration here. Because of our current payroll situation, which no political party has the will to tackle, boosting incentives would be tough.

“We may need then to focus more on ‘intrinsic motivation’, using tools that unearth the deeper sense of pride that some have in public service and encouraging those people to multiply in number, rise to the top, and change the value system and eventually the culture of the government organisation of this country.”

Franklin Cudjoe, Founding President of IMANI Centre for Policy and Education

This stewardship approach, according to Mr Cudjoe, emphasized empowering public officials who are intrinsically motivated to champion ethical leadership and national prosperity.

By nurturing such individuals, there is potential to transform the prevailing value system and, ultimately, the organizational culture within Ghana’s public sector.

Proposed Reforms: A Shift Towards Stewardship

To complement existing PFM strategies, IMANI proposed the “Revitalizing the Economy through Stewardship & Ethical Transformation” (RESET) model, which includes several reforms such as an institutionalised vehicle procurement policy for public officers.

Here, Mr Cudjoe advocated for a policy mandating that ministerial vehicles be procured en bloc every ten years, with existing vehicles auctioned off and luxury vehicles prohibited.

Franklin Cudjoe further proposed security of dedicated funding for key initiatives, urging the government to ensure that essential programs like the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), Ghana Education Trust Fund (GETFund), and Free Senior High School (FSHS) are financed through direct taxes, preventing capping or repurposing of these funds.

He also proposed the establishment of an open selection process for the Auditor-General, involving both the Public Services Commission and Parliament, with a convention allowing the opposition party to nominate candidates.

In his call for restructuring Ghana’s legal oversight, he suggested that the government must assign all criminal prosecutions to the Office of the Special Prosecutor (OSP), create a Solicitor General role to handle government civil cases, and establish an Office of the President’s Counsel within the presidency.

“The stewardship model aims to balance that by providing a complement to controls and restraints. We wholeheartedly accept that one can not switch completely from principal-agent based bureaucratic models to a stewardship paradigm.

“However, bureaucratic controls can be made less soulless and hollow by infusing the spirit of stewardship into public sector governance. How will this work in practice?”

Franklin Cudjoe, Founding President of IMANI Centre for Policy and Education

Additionally, Mr Cudjoe’s RESET model advocated for a mission-based approach to public sector reform, focusing on key actions such as voluntary commitment to openness.

He encouraged ministers and chief directors to voluntarily adopt a framework promoting transparency and stakeholder collaboration in defining sectoral visions.

While calling for a strong commitment to open data practices, ensuring that information is readily accessible to the public, Mr Cudjoe also called for regular public engagements.

Here, he advocated for conducting bi-weekly hybrid town halls to openly discuss procurement processes, performance metrics, operations, milestones, and monitoring and evaluation outcomes.

Mr Cudjoe recommended a stakeholder enrollment, which enables citizens to join stakeholder groups through a simple digital enrollment system, fostering inclusive participation.

To ensure efficiency, Mr Cudjoe called for the implementation of monthly polls among stakeholders to gather feedback, with bi-annual evaluations to celebrate progress and identify areas for improvement.

This approach aims to infuse the spirit of stewardship into public sector governance, making bureaucratic controls more meaningful and aligned with citizens’ interests.

“Naturally, this model, which we are calling RESET – Revitalising the Economy through Stewardship & Ethical Transformation – will not replace the formal audits and other PFM controls. Our hope is that it will invigorate them. Bring the essence in them to the fore and make them more meaningful to citizens.”

Franklin Cudjoe, Founding President of IMANI Centre for Policy and Education

The persistent challenges in Ghana’s public financial management underscore the need for a paradigm shift from traditional bureaucratic controls to a stewardship model that emphasizes ethical leadership and intrinsic motivation.

By adopting the RESET model, Franklin Cudjo believes Ghana can pave the way for a more transparent, accountable, and efficient public sector, steering the nation away from the precipice of fiscal crises and towards sustainable economic prosperity.

It is imperative for all stakeholders—government officials, civil society, and citizens alike—to collaborate in refining and implementing this model or similar stewardship frameworks.

The time has come to break free from the cycle of ineffective reforms and to embrace a transformative approach that truly serves the public interest.

READ ALSO: Ghana’s Oil Policy Shift Alters ENI, Springfield Unitisation