The recent petition of Okatakyie Kwasi Bumangama II, Chief of Sefwi Wiawso in the Western North Region, to former John Mahama, has brought to light the pressing issue of the diminishing powers of traditional chiefs in Ghana.

The chief’s lamentations about the erosion of authority shed light on a broader concern that has been brewing for years.

As the nation strides forward in its journey since independence, the once-unquestionable authority of chiefs is facing unprecedented challenges, prompting a critical examination of the role of traditional leaders in contemporary Ghana.

“I am glad you have visited me in my palace. Let me make this point that politicians have taken the powers of the chiefs, who are now powerless to the extent that people I summon to appear before threaten to take me to court but this was not the case in the past.

“If [Mr Mahama] wants to come back then he should give us that power again and we will all support him.”

Okatakyie Kwasi Bumangama II

Traditionally, chiefs in Ghana have been the custodians of culture, tradition, and the embodiment of community authority. Their influence extended beyond mere governance, encompassing matters of dispute resolution, cultural preservation, and societal cohesion. Chiefs played a pivotal role in shaping the socio-cultural fabric of their communities.

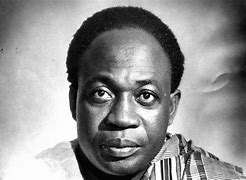

Historically, Kwame Nkrumah, the first President of Ghana, had a significant impact on the traditional chieftaincy system in Ghana.

Nkrumah pursued a policy of centralization of power to achieve rapid development. This included the centralization of authority in the national government. As a result, the influence and powers of local chiefs were diminished, as they were traditionally the custodians of local governance.

Nkrumah’s government took steps to diminish the influence of traditional authorities. The Chieftaincy Act of 1959, for example, sought to regulate chieftaincy and limit the powers of chiefs. Some traditional titles were abolished, and the government aimed to modernize local governance structures.

Nkrumah established regional and district assemblies as part of the process of decentralization. These bodies were intended to be more aligned with the government’s development goals and reduce the influence of traditional authorities in local governance.

Nkrumah’s administration was strongly nationalist and socialist. The government aimed to create a unified and modern state, and this sometimes came into conflict with traditional systems. The focus on national identity and unity often marginalized local and ethnic identities, including those represented by traditional chiefs.

Many traditional chiefs were opposed to Nkrumah’s policies, as they perceived them as a threat to their authority and the traditional way of life. Some chiefs were critical of the centralization of power and the erosion of their traditional roles in local governance.

After Nkrumah was ousted in 1966, subsequent governments in Ghana took different approaches to the chieftaincy system. Some administrations sought to restore the traditional authority of chiefs, recognizing their cultural and historical significance. However, the relationship between the government and traditional authorities continued to evolve over the years.

It’s important to note that perspectives on Nkrumah’s impact on chiefs may vary, and opinions on the balance between centralization and traditional governance may differ among Ghanaians.

Notwithstanding remnants of the impact of the Nkrumah administration linger on.

Okatakyie Kwasi Bumangama II’s expression of concern over the waning powers of chiefs reflects a broader trend observed across the country. The chief attributes this decline to constitutional provisions that have, over time, curtailed the authority traditionally vested in chiefs. The implications of this shift are profound, impacting not only the chiefs themselves but also the communities they represent.

In the past, chiefs held the authority to summon individuals and resolve disputes within their communities. However, Okatakyie Kwasi Bumangama II’s assertion that people now openly defy summons and even threaten legal action against chiefs underscores the stark transformation in power dynamics. This shift raises questions about the effectiveness of traditional dispute resolution mechanisms and the overall relevance of chiefs in the face of modern legal structures.

One of the key factors contributing to the decline in the powers of chiefs is the increasing politicization of traditional institutions. Chiefs, who were once revered as impartial figures, are now entangled in political webs. The influence of politicians on chieftaincy affairs has not only compromised the neutrality of chiefs but has also contributed to the erosion of their authority.

However, the chief’s suggestion that politicians should restore the powers of chiefs raises complex questions about the intersection of traditional authority and modern governance.

While modern governance structures are essential for progress and development, it is equally crucial to recognize and preserve the cultural heritage that defines a nation.

The Fourth Republic as made significant strides to ensure traditional authority finds expression in national governance by the establishment of the laws that recognizes the institution.

However, its perceived involvement in ‘galamsey’ and land resale to multiple buyers exacerbates the already diminishing authority of the palace.

Ultimately, the preservation of Ghana’s cultural heritage hinges on finding a balance that honors the past while embracing the opportunities of the future.

READ ALSO: NDC’s Flagbearer Hints On More Policies To Revamp Ghana’s Economy