The government of Ghana is confronted with a series of Hobson’s choices regarding its current debt stock. This short briefing note summarizes IMANI’s preliminary findings from an analysis of potential sovereign debt restructuring in Ghana.

- Should it restructure the debt or persist in the hope that the signaling effect and maximum inflows of a potential 3-year $3 billion IMF deal will make it possible to push the debt can farther than the road?

- Should it restructure only the domestic debt (debt owed to Ghanaians who have bought government securities such as treasury bills) or only the external debt (debt owed to foreigners who have bought Ghana’s Eurobonds and given out various loans for various projects? Or both?

- Should it try to bring all creditors together in a single decision-making forum (such as a “creditor committee”) or attempt to engage them in informal consultative conferences and surveys?

- Should it attempt to address the debt issues purely through contractual negotiations or should it complement negotiations with legislative support (make laws to ease its way)?

These questions present some of the most formidable analytical challenges the Ghanaian government has ever faced. IMANI’s analysts wonder if the government recognises this fact, if it has the leadership to mobilise the nation behind the choices it makes and whether it has the temperament to manage inevitable dissent, especially from the official political opposition and the country’s highly vocal civil society movement.

Context: IMF Engagement

The speculations about a potential debt restructuring by the government of Ghana arose in the context of the commencement of formal negotiations this week between the government and the IMF on a possible bailout package through the so-called “extended credit facility” (ECF). (Side note: the government’s attempts to solicit views and inputs into this whole effort have been perfunctory at best in line with a general disinterest in building national consensus on critical issues).

The IMF’s policy when designing a bailout for a country that has serious debt challenges can be summed as follows:

In determining whether a country has unsustainable debt, the IMF evaluates, first, the country’s capacity to carry debt and then the trajectory of revenues and repayments to see if in the medium-term the country will face debt distress or is already in distress.

Here is how the IMF assesses whether either condition has been met during the so-called Sovereign Risk & Debt Sustainability Analysis:

So is Ghana’s Debt Sustainable?

As indicated above, the starting point for deciding if a country can continue servicing its debts without defaulting in the medium term or triggering economic collapse is to look at the country’s capacity to carry debt. In the IMF world, this is done through the Country Policy & Institutional Assessment (CPIA) which is led by the World Bank. If the results are stellar, the country is classed as having high capacity. If it is good but not stellar, the country is said to have “medium” capacity. “Low” is the obvious bottom rating.

Ghana is currently rated as having “medium capacity”. What that means is that the thresholds and benchmarks used to assess when a country’s debt is too much are looser for Ghana than for countries rated low. Ghana used to be ranked second across Africa. This is how it fared in 2012:

It declined to 7 in 2019 and slid to 8 in 2020.

It is instructive to note in this regard that it is not only Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) who have complained about a fall in the quality of Ghana’s institutions and its policymaking process. It is quite something to see Uganda now beat Ghana on policy and institutional quality. That notwithstanding, Ghana is considerably above the regional average, hence its medium rating.

Also, Ghana is not classified among resource-rich countries in a counter-intuitive assessment which suggests a more diversified economy.

The mechanics of how the CPIA feed into the final debt sustainability numbers can be seen in this IMF chart here:

Once, debt carrying capacity based on institutional and policy strength has been accounted for, it is time to look at the actual flows of money for debt servicing: in and out. And to try and estimate the liquidity and solvency factors impacting the debt sustainability trajectory.

An analyst doing this first checks the debt ratio using this IMF equation:

Next, one tries to assess the time effect of repayment obligations using another IMF equation:

When such analysis was last performed for Ghana, the IMF said the situation was quite dire BUT Ghana’s debt was still sustainable given some caveats.

The judgement on sustainability was based on comparing certain important ratios of Ghana’s debt to certain macroeconomic measures of its economy and assessing divergence:

What’s the IMF’s Record in Judging Ghana’s Debt Sustainability?

In 2015, when Ghana entered into its previous IMF program, the IMF judged the country’s debt to be sustainable based on projections of how the debt will accumulate and Ghana’s capacity to service. As it turned out, the IMF was far too optimistic.

In June 2021, it was less sanguine about the situation, but by ignoring, at the prompting of the government, the impact of energy sector liabilities, Cocobod’s deteriorating financial circumstances (which ultimately devolves to the government) and various arrears and contingencies, it produced a baseline scenario of how the country’s debt will evolve and changes to that scenario in the event of certain shocks, such as inability to borrow from the capital markets (i.e. “loss of market access”)It w. That baseline scenario, as already mentioned, presented Ghana’s debt as sustainable but on a very borderline basis.

It was clear even then that the market, on the other hand, had already started, way back in 2019, to negatively revise its opinion on the riskiness of Ghana’s debt. Investors were asking for more discounts when buying Ghana’s debt (so “spreads” on the debt were rising).

What is the situation today?

First, let us look at the thresholds for the ratios preferred by the IMF in determining if a country can continue servicing their debts without causing damage to the economy. Here:

Ghana’s actual and projected numbers from 2019 to 2022 are as below:

In 2022, the IMF expected the total external debt to the total GDP to be 40.9%. The maximum threshold as readers can see above is 40%. Ghana’s total external debt today is $31 billion (adding recent borrowings). Due to depreciation of the Cedi, the GDP, despite a massive administrative adjustment by the government, has fallen to $58 billion, as per the latest budgetary numbers from the government for 2022:

Consequently, instead of 40.9%, the ratio is now 53%.

Bank of Ghana exports data for 2021 and data so far for 2022 can be cross-analysed to generate a figure for 2022 of $14.5 billion taking into account relatively higher oil numbers, due to rising prices (significantly lower than the government’s midyear projection though) and lower numbers for gold and cocoa due to production challenges.

Instead of the projected 128%, the number rises to an alarming 221%.

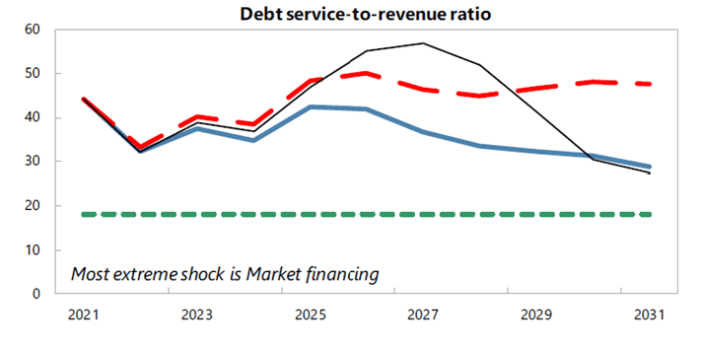

Debt service to Revenue is currently estimated at 60%. This is because revenue projection for 2022 is currently GHS 80 billion whilst interest payment alone (i.e. without accounting for amortisation) is at 41.36 billion.

The 60% figure is well in excess of the projected 32% and massively in breach of the 18% threshold in the IMF’s debt sustainability framework (DSA). Debt service to export is about 32%, which is more than double the projected 14.8% or the 15% DSA threshold.

Ghana’s debt is thus technically unsustainable based on the IMF’s standard yardsticks. However, the IMF has the discretion to look at country specific factors, such as the fact that external debt servicing is less than 10% of export revenue, and various capacity for adjustment related factors when making the ultimate decision as to whether a credible plan is underway to restore sustainability.

When the IMF chooses to overlook its usual constraints regarding lending to countries with unsustainable or near unsustainable lending, it turns to its “exceptional access” policies, such as the “lending into arrears” rules, which permits it to lend to even countries that may already be in default on some of their debt.

Countering against such a lenient view of this situation is the fact that the IMF was explicit in its last assessment that sustainability is hinged on continuing market access, which currently Ghana has lost.

On top of all this, Ghana is number 5 on the list of countries that have nearly maxed out their total quota for IMF support, even under the new COVID-triggered loosening of quota limits. In fact, should the IMF approve the $3 billion request, Ghana will shoot to the top of the table bar none (i.e. even outflanking Ethiopia).

Which brings us squarely to the issue of whether, in the absence of market access ahead of a Fund program, “fiscal consolidation” (cutting government expenditure whilst lifting revenue) alone would be enough to achieve sustainability without debt structuring. Here is what the IMF said in the 2021 Ghana Debt Sustainability Analysis report.

Assuming the IMF concludes that without debt treatment, Ghana’s debt is not sustainable? In those circumstances despite eligibility for “exceptional access”, some “debt treatment” (i.e. restructuring) may still be required.

In such circumstances the issue we started with then assumes outsized proportion: should Ghana accept debt restructuring as a condition for an IMF program?

The 3-part Choice: Domestic, External or Both

Analysts who specialise in debt restructuring looking purely at the indicators would suggest that Ghana ought to restructure both domestic and external debt.

This is because Ghana meets three of the four conditions IMF analysts usually set for that determination:

As can be seen from the chart above, only the bank credit to private sector condition is not met by Ghana.

There is of course a considerable burden in conducting a simultaneous domestic and external debt restructuring process. And, of course, there is only so much capacity in the Finance Ministry and the Presidency.

In the case of an external restructuring, Ghana has to contend with very different creditor categories with vastly different power dynamics and reputational consequences:

Benu Schneider simplifies what is possible as far as external debt is concerned as follows:

In short:

- Debt to the IMF, World Bank, AfDB and other multilaterals cannot be restructured in Ghana’s current situation. They typically require official multilateral initiatives like HIPC.

- Debt owed to countries like the US, the UK, Germany, China and other “bilateral partners” require a dedicated program which will require the convening of the donors to determine the terms of engagement. This will take many months. Luckily, Ghana does not owe a lot of money to China so it is unlikely that such a convening would take the two years that it took Zambia but it definitely not be done in a couple of months.

- It is very unlikely that Ghana will try to default on its various Letters of Credit (LCs), bank-guaranteed supplier credit and conventional bank loans as that would impact severely on a wide range of infrastructure projects and resurrect dumsor (the country’s perennial power crises), posing an existential threat to the stability of the government. At any rate, cutting a London Club deal will take not less than one year as well.

- The country’s Eurobond portfolio is thus where a lot of the emphasis shall be placed in any external debt restructuring. Ghana had about $13.1 billion of Eurobonds outstanding at face value at the end of 2021. By the end of this quarter, it should reduce to about $12.4 billion.

Besides constituting nearly half of the stock of Ghana’s external debt, eurobond issuances are also Ghana’s costliest external debt, increasing the temptation for restructuring. According to analysts, nearly $7.5 billion of the principal must be cleared by 2032 ($1.5 billion of which is due in just 3 years). Of the 16 or so outstanding bonds, 14 have collective action clauses that makes it easier to convene “creditor committees” to negotiate an en masse agreement.

Yet, the Eurobond debt service burden is still only about 12% of total revenues and thus, per our earlier estimates in this note, just 20% of the overall public debt service burden. In fact, Ghana’s total external debt service burden is about 25% of the entire annual debt service burden. In these circumstances, some analysts contend that viewed only from the point of view of the liquidity factor (instead of both liquidity and solvency considerations), the domestic debt, because it constitutes 75% of the annual debt payment burden, ought to be tackled with greater urgency.

Restructuring Domestic Debt Alone

When considering the restructuring of domestic debt, a government usually only has three broad strategies as follows:

- Shaving off some of the principal amount (“face value reduction” or “haircut”).

- Changing the tenor or maturity of the debt, which is to say deferring payments.

- Lowering the initial interest rate of the debt instruments.

These types of restructuring activities in relation to domestic debt happen more often than many people suppose. According to the Florence-based European University Institute’s Aitor Erce, domestic debt restructurings nowadays exceed external restructurings in number.

African countries have now overtaken Latin American countries in their preference for domestic debt restructurings.

The only two instances of domestic debt restructuring in Ghana, in 1979 and 1982, primarily featured demonetization rather than principal haircuts or interest rate reduction.

Will it be easier to restructure the domestic debt instead of the external one?

According to Aitor, domestic debt restructuring tend to be quicker. 42% of domestic debt restructurings happen in less than 6 months; only 13% of external ones do.

However, for various reasons, affected investors tend to lose more money during domestic restructurings:

Though “simpler” than external variants, domestic debt restructuring can still get complex if sophisticated investors are involved in the negotiations. Take the Greek debt crisis in the aftermath of the 2008-2009 international financial meltdown for instance. 86% of all Greek debt was issued under Greek law, making the process a predominantly domestic restructuring one.

The Greek government exchanged existing debt for new ones with markedly lower returns but it also added various enhancements to try and dampen investor resistance.

Because Greece was a member of the European Union, it could also fall on the European Financial Stability Facility to design the debt exchange mechanism resulting in a secondary offer to investors: the EFSF Note:

Unfortunately, regional mechanisms for debt crisis responses are virtually non-existent in Africa, so each country bears its own woes.

Greece also came up with a creative third offering that linked the likelihood of affected investors getting paid to the country’s economic performance as measured by EUROSTAT, the pan-European statistics body. The so-called “GDP warrants” introduced additional game-theoretic elements into the whole debt restructuring affair:

Should Ghana decide to go the debt restructuring route, would such creative measures be viewed as credible by investors? Would investors trust statistics from the local authorities for use in designing such contingent triggers, including statistical parameters such as “GDP growth”?

Factors to consider in any Domestic Debt Restructuring Exercise

In addition to the “speed advantage” of domestic debt restructuring (especially given the government’s apparent need for haste) and domestic debt’s 75% contribution to debt service costs, the fact, as illustrated by the Greek case, that local law is more amenable to government desires also favours a domestic debt restructuring exercise at present.

Should the government be inclined to include domestic debt in any planned debt restructuring exercise, it would be minded to consider the following points very carefully.

First, a decision has to be made if only listed debt (essentially bonds and treasury bills) shall be considered or other government liabilities like loans and contractor arrears will also be touched. Because listed debt is easier to track and is more standardised, most analysts assume that it is the only part of the debt that will be restructured.

If so, then attention has to be paid to the different categories of creditors. Below, the “client type” term refers to the current classification of domestic listed debt creditors.

Of somewhat less importance is the definition of “government debt” itself. Different parts of the government can incur debt, sometimes with varying character:

In Ghanaian context of debt, the “central government” is the most dominant player. However, there are important exposures stemming from state owned enterprises (SOEs) and guarantees.

From the Ghana Fixed Income Market (GFIM) data posted above, it can be seen that exposure to central government debt is concentrated among two main broad classes of creditors: commercial banks and financial sector actors (like insurance and pension operators).

•Stripping out about GHS 9 billion of Bank of Ghana and Cocobod securities, the commercial banks hold about GHS 65 billion (~$6.5 billion) of the ~GHS 190 billion ($19 billion) domestic debt (– ~34%). But total exposure to public & quasi-fiscal debt may be significantly more as Banks are sometimes ultimate backstoppers for other debts owed to the private sector (such as “contractors”) by the government .

•Institutional Investors and Businesses hold ~26%

•Individuals & Households hold ~13%

•Foreign Investors hold ~12.3%

•Pension Funds hold ~7%

•Insurance, Rural Banks & Others hold ~7.7%

It is important to remember that the government of Ghana has also borrowed through special purpose vehicles like the Daakye Trust and ESLA PLC, which are, by law, commercial entities in their own right. ESLA and Daakye can be sued on their own account and some sovereign rights may not apply to them.

Whilst households and individuals hold just about 13% of government debt, they are also the most politically significant group. They are the ones most likely to bring class action suits against the government and mount political agitation to stop the process as they are not as exposed to government pressure to the same extent as the banks, institutional funds and treasury departments of large companies.

Businesses that operate “floats” of various kinds, such as those in the fintech, telecoms, gambling/lotteries and related areas have traditionally used government securities to hedge against inflation and will likely resort to the courts to injunct the process except for the large companies whose political economy exposure in Ghana reduces their incentive to oppose government plans.

All in all, it is estimated that more than 1.4 million people are directly exposed to government securities judging by the number of depositary accounts in the country. This is a numerically significant political force.

The Special Case of the Banks

Because the commercial banks hold one-third of Ghana government’s debt, and in view of the ongoing financial sector cleanup, their situation deserves special mention.

Some banks are of course more exposed than others. Whilst most private banks were cutting their holdings of government debt securities, GCB (a bank with significant government shareholding), for instance, has been doubling down, adding roughly 500 million between 2021 and 2022.

Agricultural Development Bank (ADB), also a state majority owned bank, on the other hand, has cut its holdings by almost 25%.

Some private banks like Zenith have followed GCB’s lead by increasing their holdings.

Across the industry as a whole, however, the fact remains that income from government securities has been rising even as income from the “normal” operational activities of lending and trading drops. Some analysis suggest that income from government securities has outstripped interest income and now hovers around the 50% mark. Interest income on the other hand seems to be trending towards the 30% industry-wide average mark.

With government securities constituting nearly 30% of assets, and exceeding 45% of income (due to the high concentration of “investment” funds in government securities among Ghanaian banks), any process that cuts face value (“haircuts”) will hit the risk-weighting of banks’ capital. Similarly, any process that touches coupons/interest rate will hit the bottom-line (profit after tax) of banks massively.

Banks with a capital adequacy ratio below 17% may well become technically insolvent if a haircut of 25% or more takes place.

Instructively, technical solvency indicators for Ghanaian banks has been dropping due to risk adjustment of the value of assets despite many financial institutions being cavalier about marking their government securities to market after massive price drops on the secondary market. To the extent that some banks will require government financial assistance to weather any storms triggered by domestic debt restructuring, the total savings my be significantly less than assumed on face value. In fact, in some restructurings the overall stock of public debt actually grows even if debt service pressures are alleviated.

On the positive side, Ghanaian banks have the second or third highest (depending on risk adjustment) return on assets in the world and thus a good number of them may be able to withstand a significant hit to profitability.

Because some banks and financial institutions are already experiencing significant liquidity, capital and solvency challeges, IMANI strongly advises that prior to any restructuring activities in the local market, a fresh asset quality review be conducted.

Non-Bank Actors

Other financial sector actors will likewise be heavily impacted.

Because regulatory guidance strongly favours investment in government debt securities, many investment funds in Ghana have stocked up heavily on treasury bills and government bonds.

About 25% of insurance industry assets is in government securities. The corresponding number is about 30% for pension funds.

Foreign Investors in Domestic Debt Market

Whilst foreign investor participation in Ghana’s debt markets has dropped from nearly 40% just a few years ago to just a little over 12% today, that number is still significant in absolute terms.

Nearly $2 billion equivalent of foreign investor money is still invested in treasury bills, government bonds and notes.

Some of those debt instruments, amounting to about $800 million, are actually denominated in dollars.

These investors represent the highest level of litigation risk for any attempted domestic debt restructuring. Their interest in suing to prevent any harm to their portfolios is very elevated and government’s political economy leverage is lowest where they are concerned.

Risks to Debt Restructuring

To summarise, the greatest danger to a successful domestic debt restructuring on the technical front is litigation.

Worldwide, that risk has substantially risen for all types of restructuring, domestic or external.

At the domestic level, however, the fact that government debt securities like bonds and bills are governed by local law makes the Greek approach feasible. Greece introduced laws in parliament with retrospective effect thereby overcoming the absence or insufficiency of “collective action clauses” that would have permitted the government from changing the terms of the debt it had borrowed.

We see the government’s inability to build political consensus as the biggest challenge ahead constraining any attempt to resort to using Parliament to speed up the process of renegotiating the terms of its domestic debt. We do not believe that the government’s promise of an “industry-led” process is credible since apart from the banks (who hold only one-third of the debt) such a model would not be viable for the rest of the fragmented private sector.

IMANI’s assessment is that new legislation would be required to smoothly undertake any domestic debt restructuring but the political costs are very high.

The official political opposition will make much of any attempt to penalise Ghanaian investors to the perceived advantage of international investors if the government tries to circumvent litigation risk by ignoring external debt holders and non-resident holders of domestic debt.

The Opposition will however be torn between the political gains from the fallout of a botched restructuring and the prospect of obstructing any restructuring at all and thereby sharing the blame for undermining the IMF program (should debt treatment become a condition for a program).

Source: Benu Schneider

Should the Opposition take a principled policy stance that both the domestic and external debt be restructured, they will find grounding in research that shows that restructuring both external and domestic debt leads to the deepest economic recovery for affected countries after a steep initial hit.

The government will find cold comfort in the same analysis that suggests that recovery terms for doing only domestic debt restructuring are better than for doing only external debt restructuring.

Can Restructuring be Done Right?

The IMF provides a substantial framework for doing domestic debt restructuring with flair:

IMANI’s position is that any restructuring affair in Ghana will face considerable scepticism because of a lack of trust in the ongoing fiscal consolidation program as a whole.

Only 34% of targets in the country’s last strategic public financial management (PFM) process (up to 2018) were met despite the formal inclusion of all key domestic and international public actors.

Performance in budget execution for both debt and expenditure dropped rather than rose significantly over the period.

88% of central government transactions in financial statements of the country’s financial controller in a large sample reviewed by public auditors were found to have bypassed the central accounting system, the GIFMIS.

Fiscal slippages continue unabated.

When the Eurobond door was shut in the face of the government, it did not implement proper austerity. It simply increased domestic borrowing by 480% to finance mostly recurrent expenditure. Cost of borrowing, a key factor in the IMF’s 2021 debt sustainability prognosis for Ghana, is rising alarmingly.

Cost management in government business is abysmal. IMANI is currently investigating the continued accumulation of energy sector liabilities, which some analysts claim may hit $12 billion in years to come, effectively increasing the public debt by more than 20%.

IMANI’s analysts were frightened to discover that the national oil company, GNPC, which a few months earlier had tried to pressure the pricing regulator, the PURC, to increase the price of gas it sells to the utilities based on a claimed average cost to it of $7.9 per MMBTU (a unit of measure), had quietly done a deal to sell gas for just $1.72 to a company called Genser. The potential losses to the country are on the order of $1.5 billion over the life of the contract.

In short, there is a widespread scepticism about the government’s commitment to fiscal consolidation. Seeing that the IMF in previous programs has been complicit in the government’s rosy forward-looking forecasts and failures to hit fiscal reform targets, the overall credibility of any adjustment program, including any debt restructuring, is very much on the line here.

Should a domestic debt structuring lead to a broken fixed income market, no IMF financial injection will make a difference. The government borrows more than GHS 12 billion ($1.2 billion) a month from the local fixed income market, a good chunk of which goes into rolling over existing debt.

No IMF program can inject even $100 million a month directly. Nor will any situation that triggers a local financial sector crisis be viewed favourably by international investors. Which means there is a very real risk of damaging both local sources of financing for the national budget and external perception of recovery, and with the latter any chance of restoring the country’s access to the Eurobond market.

The Hobson starkness of the choices facing the government is as follows: restructuring external debt will prolong the shutout from the Eurobond market forcing the overreliance on the domestic debt markets that has seen borrowing costs surge through the roof. Such a scenario will compound inflation and exchange rate depreciation and deepen the fiscal hole. Restructuring the domestic debt may shut the government out from the local market if investors simply fail to subscribe to any new government issuances. Not restructuring either or resorting to cosmetic measures could undermine any IMF-backed adjustment effort.

In the above context, it is important to remember that weak restructuring effort will likely just delay another debt crisis. Globally, it takes on average two restructurings to stabilise a debt crisis in the medium term. Some countries become “serial defaulters” in the process. As the IMF’s Tamon Asonuma shows, almost 41 countries have earned that ignominious title.

The government faces daunting choices. Leadership would be crucial in building confidence and preventing debt recidivism. Like all burdens, this one too will become lighter if it is shared collectively by those it affects, the people of Ghana. No time is better than now for the government to show its mettle in dispelling mounting scepticism and cynicism about its commitment and capability to get the debt crisis response right.

Failure will have consequences too dire to contemplate.